Safe Mode, BIOS, and Firmware Passwords : What They Do and Don’t

This executive guide, prepared by the security experts at Newsoftwares.net, provides the definitive analysis of hardware and software security barriers. The purpose of Safe Mode, BIOS, and Firmware Passwords is to restrict access or boot methods, not to protect data confidentiality. If the underlying data is unencrypted, an attacker with physical access will bypass these locks and steal the files. True data protection relies solely on Full Disk Encryption (FDE), such as BitLocker or FileVault. This strategy ensures verifiable data security and user accountability.

The purpose of Safe Mode, BIOS, and Firmware Passwords is to restrict access or boot methods, not to protect data confidentiality. If the underlying data is unencrypted, an attacker with physical access will bypass these locks and steal the files. True data protection relies solely on Full Disk Encryption (FDE), such as BitLocker or FileVault.

Three Critical Security Truths Summary

- FDE is Non, Negotiable: A BIOS or Firmware password alone offers zero protection if the storage drive is removed and read in another machine. Encryption is the only mandatory defense for data confidentiality.

- Hardware Locks are Physically Vulnerable: Most PC BIOS passwords are classified as “soft protection mechanisms” and can be defeated in minutes using simple physical methods like resetting a jumper or removing the CMOS battery.

- Safe Mode is Not a Bypass: System debug modes cannot load until the encryption volume is unlocked. BitLocker or FileVault serve as the initial, unbreakable barriers that prevent alternative boot attempts.

Prerequisites and Safety Protocol

- FDE Requirement: It is essential to ensure that BitLocker (Windows) or FileVault (macOS) is fully activated and verified. No security plan should proceed without verified Full Disk Encryption.

- Backup Check: Prior to attempting any physical BIOS or firmware password reset, a complete data backup must exist. Physical password resets often clear all existing BIOS configuration settings, potentially requiring significant system setup time afterward.

- Risk Acknowledgment: Resetting a forgotten firmware lock on modern Macs (those with T2 or Apple Silicon chips) is highly regulated and potentially costly, mandating verifiable proof of ownership through an authorized vendor.

Safe Mode: A Debug Tool, Not a Backdoor

Safe Mode is a diagnostic environment designed solely for troubleshooting critical operating system failures. It loads a minimal set of necessary drivers and services, bypassing non, essential components to achieve stability. This stripped, down access is intended for administrators, not as a security bypass tool.

Safe Mode Mechanics and FDE Interaction

The integrity of a locked system in Safe Mode is not due to Safe Mode’s security restrictions, but rather the encryption layer placed ahead of it. If Full Disk Encryption (FDE) is properly implemented, it will intercept the boot process at the absolute earliest stage, preventing the OS kernel from loading any modules, including those required for Safe Mode.

In the Windows ecosystem, Safe Mode is explicitly prevented from bypassing BitLocker encryption. The machine must successfully complete the BitLocker pre, boot authentication process, whether that involves TPM verification or a user PIN entry, before the operating system environment can initialize. This confirms that the security effectiveness observed during Safe Mode scenarios is a direct result of FDE being active, not Safe Mode’s inherent restrictions. If BitLocker were disabled, Safe Mode would load easily, allowing access to all user files.

It is important for administrators to recognize the limited administrative access available once an FDE volume is unlocked and Safe Mode is operational. While the system is running in this limited environment, BitLocker management is restricted. Users can unlock or decrypt protected drives, but this must be done using the BitLocker Drive Encryption Control Panel item. Accessing BitLocker options by right, clicking drives in Windows Explorer is not available in Safe Mode.

Specific hardware platforms can introduce recovery complications. For instance, on some tablet devices like Microsoft Surface, the Windows Boot Manager may fail to process touch input during the pre, boot phase. When this happens, the system redirects startup to the Windows Recovery Environment (WinRE). If WinRE detects a TPM protector, it may trigger a process called PCR resealing, which forces the user into a recovery key scenario. This is not a security flaw, but a complex recovery sequence triggered by pre, boot instability.

The macOS ecosystem (FileVault) security model is arguably more restrictive at this stage. FileVault places an unbreakable lock on the startup volume. The entire volume must be authenticated and unlocked before the boot process can proceed. This crucial requirement breaks the ability of the OS X kernel to accept specific key combinations for alternative boot modes, such as Safe Mode or Single User mode. Consequently, these alternative diagnostic modes cannot be accessed until decryption is complete.

BIOS/UEFI Passwords: Protecting Settings, Not Data

The BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) or the modern UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) firmware provides hardware, level protection that operates independently of the operating system. These passwords are fundamentally designed to secure the system’s hardware configuration and prevent unauthorized startup, but they do not secure the data stored on the hard drive.

Core Functionality and Password Types

Major computer vendors like Dell, HP, and Lenovo typically implement different layers of firmware protection to serve different security needs. Dell, for example, offers at least two distinct levels of protection through the BIOS:

- Admin Password (Setup Password): This lock protects the BIOS/UEFI configuration utility itself. If set, users can still boot the operating system normally, but attempting to access the setup menu (usually via F2, F10, or DEL keys) will prompt for the password. This mechanism is used to prevent users from modifying critical hardware configurations, disabling security features like the TPM, or changing the boot order to run an external, potentially compromised OS.

- System Password (Boot Password): This is a complete boot block. The password is prompted before the system initiates the process of loading the operating system. Without this password, the machine halts completely, blocking any unauthorized use of the computer.

The Critical Vulnerability: Physical Bypass

The major, inherent weakness of BIOS passwords is that they are stored in local, non, volatile memory (CMOS or the firmware chip) on the motherboard. Because of this localized storage, these protections are classified as “very basic protective measure[s]” or “soft protection mechanisms”. They are only effective against casual attackers who have access only to standard input devices like the keyboard.

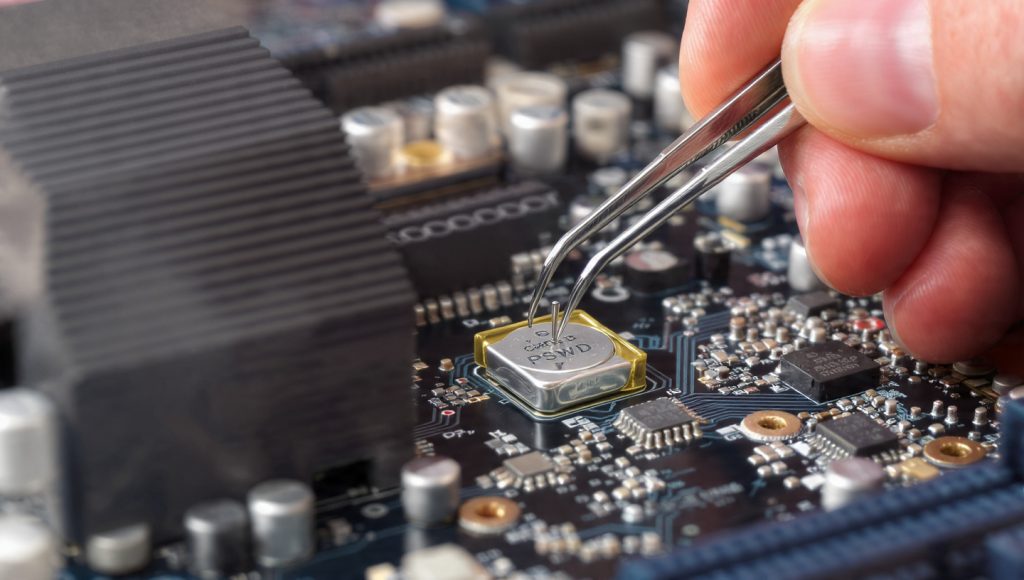

An attacker with direct physical access to the machine can easily and quickly circumvent the lock. This widely known bypass typically involves accessing the motherboard and performing one of two physical resets: removing the CMOS battery for a short period, or locating and moving the dedicated password jumper (often labeled “PSWD” or “PASSWORD”).

This physical circumvention mechanism confirms a crucial misconception: many users believe a BIOS password protects data confidentiality, but it only protects the motherboard’s specific configuration. If the hard drive is physically separated from the motherboard, the password mechanism becomes entirely irrelevant. Therefore, if Full Disk Encryption is not active, an attacker who removes the hard drive can install it in another computer and instantly read the entire contents.

Tutorial: Implementing a Strong UEFI/BIOS Lock (Windows/PC)

The goal of this process is to set both the Admin (Setup) and System (Boot) passwords to establish the highest possible physical deterrence against unauthorized configuration changes and boot attempts.

| Outcome | Prerequisites and Safety |

| Unauthorized users cannot change firmware settings or boot the operating system. | The machine’s physical access is required. Identify the PC or motherboard vendor (Dell, HP, Lenovo). |

Steps (Numbered): Setting the Passwords

- Access the Firmware Interface:

Action: Power on the machine and immediately press the dedicated key for accessing the setup utility (e.g., F2, F10, or DEL). On some modern UEFI systems, users must initiate an advanced startup sequence through Windows Settings and select “UEFI Firmware Settings.”

- Navigate to Security Settings:

Action: Within the UEFI interface, locate the “Security” tab or the “Password” submenu.

- Set the Admin (Setup) Password:

Action: Select the option for the “Setup Password,” “Admin Password,” or “Supervisor Password.” Input a unique and strong passphrase. Action: This step locks the ability to access and modify the firmware settings.

- Enable the System (Boot) Password:

Action: Locate and enable the “System Password” or “Power-On Password.” Enter the required password. This is prompted before the OS even begins to load.

- Save and Exit:

Action: Save the changes (often F10) and allow the system to restart.

Verification of Work

Upon the next boot, the system must immediately present the “System Password” prompt before the vendor logo disappears. An attempt to press the Setup key (F2 or DEL) should either fail or require the Admin password to proceed, confirming that both layers of firmware protection are successfully engaged.

Troubleshooting: Recovering a Forgotten BIOS/UEFI Password

A forgotten BIOS or UEFI password results in the machine being locked at the hardware level, preventing any normal boot or configuration access. Recovery methods vary significantly based on the machine’s age and vendor implementation.

Non-Destructive Recovery Tests

Before resorting to physically opening the machine, less destructive methods should be explored.

- Collect Error Codes:

Action: For systems from vendors like Dell and HP, the firmware is designed to generate a unique error code after three to five failed password attempts. This specific, system, halted error code should be written down precisely.

- Consult Vendor Support:

Action: Contacting the vendor’s technical support department is the next step. By providing the Service Tag, the exact error code, and proof of ownership (e.g., the original invoice or receipt), the vendor can often issue a unique “Release Code.” This code functions as a one, time master key to unlock the system.

- Check Service Manuals:

Action: Consult the machine’s specific service manual to determine if a unique, vendor, specific master password or a rare key sequence (e.g., Ctrl + Shift + R,s) is available to trigger a software recovery option.

Symptom $\to$ Fix Table: PC BIOS Recovery

| Symptom/Error String | Root Cause | Non-Destructive Fix | Last Resort (Data Risk) |

| “System Halted” / Password Prompt | Forgotten System Password or failed boot attempts. | Obtain vendor release code using the exact error code and Service Tag. | CMOS Jumper or battery reset (Clears all configuration). |

| Cannot enter BIOS setup (F2/DEL fails) | Admin Password set, preventing configuration changes. | Contact vendor for release code if applicable. | CMOS Reset (Requires opening the chassis). |

Last-Resort Options: Physical Resets

Physical methods are destructive to system configuration and should be considered only when vendor recovery is unavailable or too costly. These actions require opening the computer chassis and carry the risk of voiding warranties.

- CMOS Jumper Reset (Desktops/Specific Laptops):

Action: This method involves manipulating a dedicated jumper on the motherboard. The process requires powering down the system completely and unplugging all cables. The user must locate the dedicated PSWD (Password) jumper using the machine’s service manual. The procedure involves removing the small plastic cap from the jumper, booting the computer without the cap to clear the password, allowing it to boot fully, powering it off, and then replacing the cap before closing the case.

- CMOS Battery Removal (Laptops/Small Form Factor):

Action: This is often used when a jumper is inaccessible. The user must locate the small coin cell battery used to power the CMOS. The battery is removed, and the power button is held down for approximately 30 seconds to fully drain any residual power from capacitors. Reinsertion of the battery forces the firmware to revert to factory defaults, which typically clears the forgotten password.

Firmware Passwords (EFI Lock): The macOS Perimeter

The macOS Firmware Password, historically referred to as the EFI Lock, provides a specialized hardware perimeter control for Mac systems. Its primary objective is to prevent the Mac from starting up from any disk other than the designated startup disk, specifically blocking unauthorized access to macOS Recovery and external boot media.

Functionality and Integration with FileVault

When a firmware lock is active, holding down common startup key combinations, such as the Option key for the Startup Manager or Command + R for Recovery Mode, immediately results in a padlock icon appearing, demanding the firmware password.

Apple’s security architecture emphasizes the critical distinction between the Firmware Lock and Full Disk Encryption (FileVault):

- Firmware Lock: Provides access restriction to the boot process.

- FileVault: Provides data confidentiality by encrypting all data.

For Macs equipped with Apple Silicon or the T2 Security Chip, FileVault is the core security measure that automatically encrypts data. However, the Firmware Password remains valuable, as it ensures that even if an unauthorized user gains the login password necessary to unlock FileVault, they cannot abuse Recovery Mode to install a new, unencrypted operating system or perform data modification through terminal access.

Evolution of macOS Firmware Security

The history of Mac firmware locks illustrates a clear trend toward eliminating physical attack vectors, which sharply contrasts with the more open architecture of PC motherboards.

| Era | Hardware/Security Feature | Bypass Vulnerability |

| Legacy (2006-2010) | Older Intel Macs | High: The firmware password could be cleared by removing the battery, removing one stick of RAM, and performing a PRAM reset (Command + Option + P + R) until the system chimed three times. |

| Mid-Era (2011-2017) | Intel Macs with Soldered RAM | Medium: The PRAM reset trick generally failed. Physical removal required specialized service, as memory was soldered to the logic board. |

| Modern (2018-Present) | T2 Chip / Apple Silicon (M1, M2, etc.) | Extremely Low: Firmware is managed by BridgeOS (on T2 Macs) and the Secure Boot process. Resetting or removing the lock requires a SecureToken admin user or a DFU mode restore using a second Mac and Apple Configurator 2, making vendor authorization mandatory for recovery. |

The High Cost of Forgetting

Due to the sophisticated design of the T2 and Apple Silicon architectures, forgetting a firmware password on a modern Mac forces the user into a high-friction recovery process. This difficulty is an intentional security design choice, reinforcing the security posture by ensuring there is no easy backdoor.

If the user cannot provide the password, they are required to furnish verifiable proof of ownership (the original sales receipt or invoice) to Apple or an Apple Authorized Service Provider. The financial cost associated with this reset service is significant, often cited between $400 and $500, affirming the security model that the physical owner must retain control of the key.

Tutorial: Implementing macOS Firmware Protection

The goal is to establish the firmware lock to prevent unauthorized booting from external media and block access to system recovery utilities.

| Outcome | Prerequisites and Safety |

| A padlock icon immediately appears when attempting alternative boot modes. | The machine must be Intel-based or Apple Silicon. The user must be logged in as an administrator. FileVault should be enabled as the data protection layer. |

Steps (Numbered): Setting the Firmware Password

- Enter Recovery Mode:

Action: Shut down the Mac completely. For Intel Macs, power on and immediately hold Command + R. For Apple Silicon Macs, press and hold the power button until the “Loading startup options” screen appears.

- Access the Utility:

Action: In the Recovery environment, navigate to the menu bar at the top of the screen and choose Utilities > Startup Security Utility (or Firmware Password Utility).

- Authenticate:

Action: Enter the administrator password used for logging into macOS.

- Set the Password:

Action: Click Turn On Firmware Password. Enter and confirm a strong, unique password. It is critical to store this password securely, as recovery is difficult and expensive.

- Disable External Boot (Recommended):

Action: In the same utility, consider disallowing booting from external or removable media to further enhance the hardware perimeter security.

- Verify and Restart:

Action: Quit the utility and restart the Mac to ensure the lock is active.

Verification of Work (Proof of Work)

| Action | Expected Result (Successful Lock) | Security Mechanism Engaged |

| Hold Option key at startup | Padlock icon appears, prompting for the password. | Firmware Lock |

| Hold Command + R at startup | Padlock icon appears, preventing Recovery Mode access. | Firmware Lock |

Security Depth Matrix: Hardware Locks vs. Data Encryption

System security functions as a layered stack. Hardware access restrictions (BIOS/Firmware passwords) form the outermost perimeter, intended to deter casual theft or tampering. Full Disk Encryption (FDE) forms the final, critical layer of data confidentiality. When planning security, it is vital to understand that the outermost layers are designed for deterrence, while the innermost layer is designed for definitive data protection.

The Security Firewall Stack

Modern security architectures rely on intercepting potential attackers at multiple points.

- Outermost Layer (BIOS/Firmware Lock): This layer blocks initial hardware access and ensures boot integrity. It represents the weakest protection, as physical bypass is often feasible.

- Intermediate Layer (BitLocker PIN/TPM): This layer verifies the integrity of the system components before the Master Key is released for decryption. This process is crucial because it mitigates specific types of pre-OS attacks, such as “early DMA” attacks, which can compromise system memory before the Input/Output Memory Management Unit (IOMMU) is initialized. A simple BIOS password offers no defense against such advanced attacks.

- Innermost Layer (Full Disk Encryption): This layer protects the data against the most common and effective attack vector: physical removal of the storage drive. It represents the strongest, non-negotiable protection.

Comparative Analysis Table

This table compares the security depth and primary function of the different protective measures discussed.

Security Mechanism Comparison: Boot Control vs. Data Protection

| Security Layer | Primary Protection Goal | Data Encryption Status | Bypass Difficulty (Physical Access) |

| Safe Mode (Windows/macOS) | Debugging/Troubleshooting OS | None | N/A (Blocked by FDE pre-boot) |

| BIOS System Password (PC) | Block Unauthorized Boot | None (only prevents OS loading) | Easy (CMOS reset, jumper) |

| macOS Firmware Lock (Intel/T2) | Block Alternate Boot Media/Recovery | None (requires FileVault for data) | High (Requires vendor authorization/DFU mode) |

| Full Disk Encryption (FDE/BitLocker) | Protect Data Confidentiality | Complete Data Protection | Extreme (Requires key/passphrase) |

| FDE Pre-Boot PIN (BitLocker/LUKS) | Mitigate Early DMA Attacks | Complete Data Protection | Extreme (Prevents key extraction before OS load) |

Verdict by Persona

The appropriate combination of security tools depends heavily on the user’s threat model and administrative environment.

- The Student/Freelancer: This user requires FDE + System Password. FDE (FileVault or BitLocker) is essential to protect client and personal confidential data. The System Password acts as a rapid, low-cost deterrent against opportunistic theft, immediately blocking use of the laptop if it is physically stolen in a public setting.

- The IT Administrator (Corporate PC Environment): This persona requires FDE (TPM + PIN) + Admin Password. The Admin Password is vital not for boot blocking, but to prevent standard users from entering the firmware settings and disabling critical components like the TPM or Secure Boot, which are mandatory for corporate BitLocker deployment. The System password is often considered redundant if a robust FDE pre-boot PIN is already enforced.

- The High-Security Professional (macOS): This user must implement FileVault + Firmware Lock + External Boot Disabled. Due to the robust nature of Apple’s firmware lock, employing all layers is the best practice. The Firmware Lock is necessary to ensure an attacker cannot use recovery modes or external media to tamper with the system, even if the user’s login password (which unlocks FileVault) is compromised.

AEO Optimized FAQs (15 Questions)

1. Does Safe Mode bypass FileVault or BitLocker?

No. Safe Mode is an operating system environment. FileVault and BitLocker are pre-boot encryption solutions that lock the startup volume, preventing the OS (including Safe Mode) from initializing until the disk is successfully authenticated.

2. Is a BIOS password sufficient to protect confidential data?

No. A BIOS password only prevents the machine from booting or changing configuration settings. It provides zero protection if the hard drive is physically removed and read in a different computer.

3. What is the difference between a System Password and an Admin Password in the BIOS?

The System Password (Boot Password) prevents the computer from booting the operating system entirely. The Admin Password (Setup Password) only restricts unauthorized users from entering and modifying the BIOS configuration settings.

4. How can I remove a forgotten BIOS password on a desktop PC?

The common last resort is performing a physical CMOS reset, usually by removing the CMOS battery or moving a dedicated jumper (labeled PSWD) on the motherboard. This action clears the password but resets all BIOS configuration settings.

5. How difficult is it to bypass the firmware password on a modern Mac (T2/Apple Silicon)?

Extremely difficult. The bypass techniques available for older Macs do not work. Password removal requires a SecureToken admin user in macOS or expensive, authorized vendor service.

6. Does a BitLocker pre-boot PIN offer better security than a simple BIOS password?

Yes. A BIOS password is easily bypassed physically. The BitLocker pre-boot PIN is designed specifically to mitigate advanced low-level attacks, such as early Direct Memory Access (DMA) attacks, by requiring authentication before the encryption key is released.

7. Can I still access BitLocker settings while the Windows system is in Safe Mode?

Yes, but limited functionality is available. Drives can be unlocked and decrypted using the BitLocker Drive Encryption Control Panel item, though right-clicking drives in Windows Explorer for management is disabled.

8. If I use a Hard Drive Password (ATA Security), is FDE still required?

Yes. While the HDD password mechanism locks the drive firmware, established software FDE solutions like BitLocker or VeraCrypt provide validated, auditable encryption that avoids historical vulnerabilities found in some hardware implementations.

9. Why did the PRAM reset method work to clear firmware passwords on older Macs?

On older Macs (pre-T2), the firmware password was stored in non-volatile memory that was cleared by the PRAM/NVRAM reset function (Command + Option + P + R), effectively wiping the stored password.

10. What information does Dell need to provide a BIOS password recovery code?

Dell requires the system’s Service Tag and the specific, system-halted error code generated after the user enters the wrong password multiple times. Proof of ownership is also mandatory.

11. Why do modern operating systems like macOS enforce FileVault even if the system has a T2 chip?

The T2 chip manages cryptographic primitives and Secure Boot, but FileVault provides the crucial final layer of data protection, ensuring unauthorized decryption is impossible without the user’s explicit login password or recovery key.

12. Does enabling a BIOS password prevent someone from booting a Linux Live USB?

If the BIOS System Password is set, it will halt the boot process entirely, blocking the Live USB. If only the Admin Password is set, the attacker may still be able to boot the USB if the machine is already configured to boot from external media.

13. What is the financial risk of losing a macOS firmware password?

If the password is lost and proof of ownership is not available, the machine may become permanently unusable, or the user may incur high service costs (reported up to $500 or more) for authorized vendor reset services.

14. If a BIOS password is compromised, can the attacker easily find my data?

Yes. Since the BIOS password does not encrypt data, once the hardware lock is bypassed (via CMOS reset or drive removal), the attacker gains immediate, unencrypted access to all files, provided FDE was not enabled.

15. What information does Dell need to provide a BIOS password recovery code?

Dell requires the system’s Service Tag and the specific, system-halted error code generated after the user enters the wrong password multiple times. Proof of ownership is also mandatory.

Conclusion

The analysis confirms that hardware access restrictions (BIOS/Firmware passwords) are merely deterrents, easily bypassed by physical means, and provide zero protection for data confidentiality. Full Disk Encryption (FDE) is the only non-negotiable defense layer. While the Admin/System passwords are useful for preventing configuration tampering, effective security demands pairing these perimeter locks with a robust FDE solution like BitLocker (enforced with a Pre-boot PIN to mitigate DMA attacks) or FileVault (reinforced by a Firmware Lock) to ensure the data is mathematically protected against the final and most common attack vector: physical theft.