End-to-End vs In-Transit vs At-Rest Encryption , What’s Actually Protected

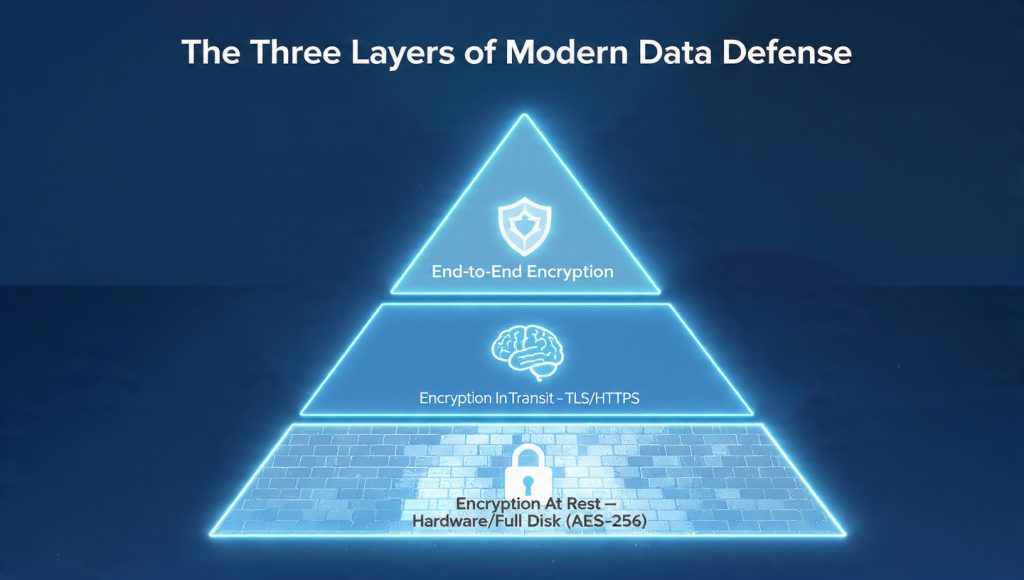

This executive guide, prepared by the security experts at Newsoftwares.net, provides the definitive framework for data protection. The word “encrypted” gets tossed around constantly, in emails, on laptops, and in cloud backups. But that label is misleading. Not all encryption protects the same data from the same adversary. When your critical file is moving, sitting in a database, or being sent via chat, it faces three fundamentally different types of threats. The simple truth is: What’s protected depends entirely on where the cryptographic lock is placed, and who holds the keys. If you rely on the wrong type of encryption, your data is exposed to insiders, cloud providers, or government requests, even if you see a padlock icon. This strategy ensures verifiable security and maximum resistance against modern cyber threats.

The word “encrypted” gets tossed around constantly, in emails, on laptops, and in cloud backups. But that label is misleading. Not all encryption protects the same data from the same adversary. When your critical file is moving, sitting in a database, or being sent via chat, it faces three fundamentally different types of threats. The simple truth is: What’s protected depends entirely on where the cryptographic lock is placed, and who holds the keys.

If you rely on the wrong type of encryption, your data is exposed to insiders, cloud providers, or government requests, even if you see a padlock icon.

One sentence promise and outcome: Stop trusting vague “encrypted” claims, understand the precise technical boundaries of In, Transit, At, Rest, and End- to-End encryption to build a truly defensible security posture.

II. Encryption In-Transit: Securing the Pipe

Encryption In, Transit (or “In, Motion”) protects data as it travels across a network. This is the security layer for nearly all internet activity.

The TLS Handshake: A Cryptographic Relay Race

When you see “HTTPS,” you are using the Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol. This protects 88.7% of all websites today. TLS doesn’t rely on one type of encryption, it cleverly uses two.

- Asymmetric Start: The client (your browser) uses slow, identity, focused asymmetric cryptography (based on the server’s public key certificate) to authenticate the server and securely exchange session secrets. This proves you are talking to the real bank, not a phishing site.

- Symmetric Finish: Once the identities are confirmed, the two parties secretly generate a fast, temporary symmetric key (the master secret). All subsequent bulk data, like streaming video or loading a large page, is encrypted with this fast symmetric key, making the connection high, speed and efficient.

The Trust Boundary: TLS creates a secure tunnel from your browser to the web server. Once the data reaches the destination server, the server decrypts it. This means the server, be it Google, Amazon, or your bank, always holds the key and can read the plaintext.

III. Encryption At-Rest: Securing the Storage Vault

Encryption At, Rest (EaR) secures stored data, whether it’s on a stolen laptop, a backup tape, or a server database. It uses powerful symmetric ciphers like AES-256 for speed.

A. Full Disk Encryption (FDE): The Hardware Lock

FDE protects the entire operating system, application files, and user data. It is the mandatory defense against physical device theft.

1. Hardware Acceleration (AES-NI)

On modern computers, FDE runs at near, zero performance cost because CPUs include dedicated hardware instructions (AES-NI) for the AES algorithm. Benchmarks show AES-256 operations running at speeds exceeding 1,100 MB/s, often limited by the speed of the disk itself, not the CPU.

2. Key Binding: TPM and Secure Enclave

FDE key management relies heavily on specialized, isolated hardware:

- Windows BitLocker: BitLocker binds its keys to the Trusted Platform Module (TPM) chip on the motherboard. The key is “sealed” to a specific, expected boot state, verified by Platform Configuration Registers (PCRs). If a hacker tampers with the bootloader, the PCR values change, and the TPM refuses to release the key, leaving the data permanently locked.

- Apple FileVault: On Macs with Apple Silicon or the T2 chip, FileVault keys are stored and managed by the Secure Enclave. This dedicated secure subsystem has its own isolated AES engine, which protects key material even if the main macOS kernel is compromised.

B. Archive Encryption: Securing Individual Files

When sharing files, Full Disk Encryption is useless. You must rely on container encryption like the .7z format.

1. Why You Must Ditch Legacy ZIP

Do not use the standard password protection offered by legacy .zip archives. These default to the weak proprietary Zip 2.0 (Legacy) encryption (often called ZIPCrypto). Security firms report an 87% success rate in cracking these files within a few hours using off, the, shelf tools.

The standard is the .7z format using AES-256, which is vastly superior.

2. The Critical Metadata Failure

The biggest operational failure in archive encryption is forgetting the single most important checkbox.

If you use 7, Zip (or any modern archiver), you must explicitly check the box labeled “Encrypt file names”. If you omit this step, an attacker can still open the archive and see a full list of all file names and sizes, for example, “Client, Invoice, 2024.pdf” and “CEO, Email, Archive.pst”, without needing the password. This metadata leakage compromises the entire privacy goal.

IV. End-to-End Encryption (E2EE): Securing the User

E2EE is the most powerful form of encryption because it changes the trust model. E2EE ensures the data is encrypted on the sender’s device and only decrypted by the recipient’s device. Crucially, the service provider (the entity running the chat app or storing the cloud file) never holds the master key and can never read the plaintext.

A. E2EE in Secure Messaging (The Signal Protocol)

Modern E2EE chat platforms like Signal use sophisticated protocols to maintain constant, perfect security.

The Signal Protocol uses the X3DH key agreement to establish a shared secret, and then uses a constantly evolving “Double Ratchet Algorithm” to generate new keys for every message. This provides forward secrecy, meaning that even if a hacker compromises today’s key, they can’t use it to decrypt messages sent last week.

Signal also hides metadata by encrypting the sender’s identity with a key the server doesn’t have, the sealed sender feature.

B. Zero-Knowledge Cloud Storage

Standard cloud services (Google Drive, Dropbox) rely on server, side encryption. They hold the keys, meaning they can be legally compelled to turn over your data in plaintext.

For highly sensitive data, the only solution is a Zero, Knowledge (ZK) cloud service. In a ZK system, you encrypt the data locally (client, side) before it ever leaves your laptop, using a tool like Cryptomator or a ZK provider like Proton Drive or Filen. The server receives only unintelligible ciphertext and cannot, by mathematical design, decrypt the data for anyone, not for hackers, and not for governments.

V. Key Derivation and Operational Resilience

The practical security of any encryption relies on two factors: the strength of the password and the integrity of the system.

A. The Key Derivation Function (KDF)

The Key Derivation Function (KDF) is the cryptographic tool that converts your human, readable password (which has low entropy) into the highly complex, 256, bit key needed for AES.

The KDF’s purpose is to be intentionally slow. It does this by forcing millions of computational steps (iterations) to transform the password.

- PBKDF2/Argon2id: Modern systems should use memory, hard KDFs like Argon2id (supported by VeraCrypt), which resist specialized GPU hardware attacks by demanding massive amounts of memory.

- Iteration Count: While older standards only recommended 10,000 iterations, current security standards now recommend high iteration counts, such as 600,000 for PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256. This ensures that even if a hacker steals the password hash, testing billions of passwords remains prohibitively slow and expensive.

B. Troubleshooting Integrity Failures

Operational problems often look like cryptographic failures, but they are usually data integrity issues.

| Symptom/Error Message | Cause and Context | Immediate Fix |

| 7-Zip CRC Failed | Cyclic Redundancy Check failure. Data corrupted during transfer (incomplete download) or due to malware/bad disk sectors. | Action: Run a malware scan, check the hard drive for bad sectors, and re, download the file from the source. |

| 7-Zip Data Error | Incorrect password or severe file corruption, sometimes caused by software misinterpreting binary data as text. | Action: Reboot the computer, or use the original files to create a new, clean archive using the exact same settings. |

| FDE Header Damaged | Physical damage or improper shutdown corrupted the volume header (e.g., in VeraCrypt), making the disk unmountable. | Action: You must use the utility to Backup Volume Header (VeraCrypt Tools menu) that should have been run when the volume was created. |

| In-Transit Failure | Certificate expired or handshake failure (common on older devices). | Action: Update the operating system and browser to support the latest TLS standards. |

C. Secure Key Sharing (The Human Element)

Since strong encryption is practically unbreakable, the weakest link is always the transfer of the password or key.

The mandate is to use ephemeral links. Services like One, Time Secret generate a link to the password that is accessible exactly once by the recipient and is then permanently destroyed. This ensures the key is never stored in a persistent message history or on an insecure server.

VI. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: If I use HTTPS (In-Transit), is my data protected on the server?

A: No. HTTPS only protects data during transmission between your device and the server. Once the data reaches the server, it is decrypted. Security on the server depends on the server’s own At, Rest security measures.

Q: Can hackers decrypt AES-256?

A: No. AES-256 is the gold standard for symmetric encryption, used by governments for top secret data. It is mathematically secure. If an AES-256 encrypted file is cracked, it means the attacker guessed the password, or the underlying KDF was weak.

Q: Why do I need E2EE if TLS is already secure?

A: TLS protects against external wiretapping, E2EE protects against the service provider. For example, in an E2EE chat, the company hosting the messages cannot read them, whereas a standard email provider using only TLS can.

Q: Does Full Disk Encryption (FDE) protect me from all malware?

A: FDE protects against theft of the drive or physical loss while the device is off. It does not protect against advanced threats, ransomware, or malicious insiders once the drive is mounted and unlocked (at which point the data is exposed in memory).

Q: What is the main risk of using the legacy ZIPCrypto method?

A: The proprietary Zip 2.0 (Legacy) encryption is fundamentally weak, with known flaws that make password cracking highly effective. Security tests show an 87% success rate in cracking these files within a few hours.

Q: Why does encryption run so fast on my laptop?

A: Encryption speeds are boosted by AES-NI (Advanced Encryption Standard New Instructions), dedicated hardware instructions built into modern CPUs. This makes the encryption process near, instantaneous, shifting the performance bottleneck to the disk speed.

Q: What is the primary job of a Key Derivation Function (KDF)?

A: The KDF converts a short, human, chosen password into a complex, high, entropy cryptographic key. Its primary job is to be computationally expensive (slow) to make automated brute, force attacks against the password infeasible.

Q: If I use 7-Zip, do I need to worry about metadata leakage?

A: Yes. By default, 7, Zip does not hide file names. You must explicitly select the “Encrypt file names” option when creating the archive, or attackers will see the contents list without the password.

Q: What is the difference between a TPM and the Secure Enclave?

A: Both secure FDE keys. The TPM (Windows/BitLocker) secures keys based on the system’s boot state (PCRs). The Secure Enclave (Mac/FileVault) is a dedicated, isolated processor with its own AES engine that protects keys even if the main macOS kernel is compromised.

Q: How does a Zero-Knowledge Cloud provider maintain data privacy?

A: ZK providers ensure the data is encrypted on the client’s device before it is uploaded. Since the encryption keys never leave the client, the provider only stores unintelligible ciphertext and cannot decrypt the data for anyone.

Q: Why does NIST recommend rotating cryptographic keys (cryptoperiods)?

A: Key rotation limits the exposure time of any single key. If a key is compromised, rotation ensures the attacker can only decrypt data covered by that key’s limited “cryptoperiod” (lifetime).

Q: If my data is unrecoverable due to a damaged VeraCrypt header, is the encryption still secure?

A: Yes. The encryption remains secure (confidential), but the data is inaccessible (loss of availability). This is a system integrity failure, not a cryptographic one. Backing up the volume header is the fix.

Q: Can I use AES-128 encryption instead of AES-256 for faster speed?

A: While AES-128 is technically strong, the speed difference is negligible due to AES-NI hardware acceleration. For maximum security, long, term archiving, and regulatory compliance, AES-256 is the mandated standard.

Q: Why are man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks a threat to E2EE?

A: E2EE is only secure if the endpoints are correctly authenticated. If a MITM attack compromises the initial key exchange (often due to an ignored security warning), they can substitute their own keys, breaking the E2EE chain.

Q: Does the GDPR Right to Erasure require me to physically destroy hard drives?

A: Not necessarily. If the data resides on a Full Disk Encrypted volume, securely deleting the volume’s master encryption key (cryptographic erasure) is a verifiable, efficient, and legally compliant method of irreversible data deletion that satisfies the Right to Erasure.

Conclusion

The definitive security strategy for data requires layering defenses based on the data’s state. Encryption in, transit (TLS) secures the network pipe, but End-to-End Encryption (E2EE) is mandatory for user privacy, structurally excluding the service provider from viewing the content. Full Disk Encryption (FDE) secures data at rest from physical threats, but the final, critical defense is operational: hardening human behavior through strong Key Derivation Functions (Argon2id) and the mandated separation of file and key during transfer. True security relies on the seamless and correct deployment of all three layers.