AES 256: Debunking the Myths of “Cracking” and Ensuring Real-World Security

Welcome to a focused, practical overview on the security of AES 256. Developed by the team at Newsoftwares.net, this article aims to cut through the sensational headlines and provide technical clarity on why AES 256 remains the global standard for data protection, security, and privacy. The key benefit is confidence: you will understand the real vulnerabilities in cryptographic systems and learn concrete steps to implement AES 256 correctly, ensuring your “unbreakable” encryption actually holds up against real-world threats.

Gap Statement

Most “AES 256 is cracked” takes mix scary headlines with half facts. They talk about math but skip the boring bits that actually get people hacked, like weak passwords, bad modes, and side channel leaks.

Short Answer

With current knowledge and hardware, a correctly implemented AES 256 key with good passwords and modern settings is not practically crackable. Every real world “AES was cracked” story you see comes from something around AES failing, not the core cipher itself.

This article shows you what “cracked” really means, where AES 256 still stands firm, and exactly what you must do to avoid being the person who had “unbreakable AES 256” and still lost all their data.

Key Outcome

If you only skim, keep these three points.

- No one has a practical attack that recovers keys from full, standard AES 256 faster than brute force in any normal threat model.

- Real breaches come from weak passwords, bad key storage, side channel leaks, and broken protocols, not the AES 256 core.

- Quantum changes the math a bit but AES 256 is chosen specifically to keep a safe margin against realistic quantum brute force. )

The rest of the piece is a practical “how not to get cracked while using AES 256” handbook.

1. What “cracking AES 256” actually means

People use “cracked” for three very different things:

- Pure brute force: Trying every possible key until one works.

- Cryptanalytic shortcut: A clever attack that beats brute force by a meaningful margin.

- Attack on everything around AES: Stealing keys from memory, breaking your password, or abusing poor code.

The math side first:

- AES is a block cipher with 128 bit blocks and key sizes 128, 192, and 256 bits.

- AES 256 has a key space of 2²⁵⁶ possible keys. That number is absurdly large.

Brute forcing AES 256 in any direct way is still completely out of reach.

On the cryptanalysis side:

- The best published single key attack on full AES uses a biclique technique.

- It trims a tiny amount of work off brute force. For AES 256 the cost is still around 2²⁵⁴ point something, which is still hopeless in practice.

Related key attacks against round reduced AES 256 exist, but they rely on strange conditions where an attacker can choose keys that are mathematically linked. That is nothing like how AES is used for normal data protection.

So when you hear “AES 256 was broken”, what usually happened is:

- Someone grabbed keys from RAM.

- A cloud instance leaked keys through a cache timing channel.

- A phone app used AES 256 in ECB mode with a four word password.

The cipher stayed solid. The setup did not.

2. Hard facts: current state of AES 256 security

Let’s separate fiction from things we can actually point to.

2.1 Brute force

Brute force against AES 256 needs around 2²⁵⁶ trials. Even at science fiction speeds, that is not going to happen.

NIST key management guidance treats AES 256 as giving 256 bit security in a classical model.

Modern vendor docs still call AES 256 “virtually immune” to brute force with current technology.

2.2 Known cryptanalytic attacks

Two families matter in public research:

- Biclique attacks on full AES.

- Related key attacks against reduced round AES 256.

Biclique attacks cut a tiny fraction of the key space. For AES 256 they still need around 2²⁵⁴·⁴ work. That is still effectively impossible.

Related key attacks against AES 256 require exotic control over keys. They do not match real world key usage where a single random key protects data.

So far, no one has published a practical break of standard AES 256.

2.3 Quantum reality check

Quantum changes the story, but not as much as some blog posts suggest.

- Shor’s algorithm breaks RSA and ECC. It does not directly break symmetric ciphers like AES.

- The main threat to AES comes from Grover’s algorithm, which gives a square root speedup for brute force.

Grover would turn:

- AES 128 into roughly 2⁶⁴ work.

- AES 256 into roughly 2¹²⁸ work.

That is exactly why many experts say: want long term safety in a future quantum world? Then AES 256 is the right size.

So the short version:

- Classical attacker: AES 256 has a towering security margin.

- Quantum attacker with a huge, real machine: AES 256 still has a giant margin.

3. Real ways AES 256 setups get “cracked”

Enough theory. This is what actually hurts people who think “we use AES 256 so we are safe”.

3.1 Weak passwords and bad KDF

If you turn a weak password straight into an AES 256 key, the practical security is limited by that password, not by 256 bits.

Common mistakes:

- Using short or dictionary based passphrases.

- Using a KDF with too few iterations or outdated settings.

- No memory hard KDF for user passwords.

Modern guidance is clear:

- Use strong passphrases.

- Use PBKDF2, scrypt, or Argon2 with tuned parameters.

3.2 Wrong mode and missing integrity

You can say “AES 256” while using it in terrible ways:

- ECB mode reveals patterns directly.

- Plain CBC without a MAC lets attackers tamper with data.

- Reusing IVs in CTR or GCM breaks confidentiality.

Common safe patterns:

- AES GCM for most data in transit.

- AES XTS for full disk encryption.

- AES CBC only when paired with a separate integrity check.

3.3 Side channel leaks

Side channel attacks extract secrets through timing, power usage, cache patterns, and similar signals.

Well known examples:

- Cache timing attacks against AES table lookups.

- Power analysis on smart cards and embedded chips.

Here AES is still strong. The implementation leaks.

3.4 Key management mistakes

NIST spends far more pages on key management than on cipher picks. That is a hint.

The painful patterns:

- Keys in source code or config files.

- Keys in logs or crash dumps.

- Production keys reused in test.

Once an attacker has your AES key, it does not matter that it is “unbreakable”.

4. How to use AES 256 correctly step by step

Let’s turn this into a concrete setup. The goal here is practical, not academic.

We will pick one common scenario:

- Encrypting sensitive files with AES 256 on a desktop or laptop.

You can adapt the same mindset to disk encryption, databases, or app traffic.

4.1 Prereqs and safety

Before you change anything:

- Confirm your OS and tools: Make sure you are on a maintained OS and using well known tools such as VeraCrypt, 7 Zip, OpenSSL, or system disk encryption like BitLocker or FileVault.

- Back up your data: Copy important data to a separate drive or cloud backup before you touch encryption settings.

- Decide threat level: Are you protecting personal archives, client data, or regulated records? This affects how strict you should be about hardware keys, audits, and logging.

- Legal and ethics note: Only encrypt and test data that you own or are allowed to protect. Do not try to “test AES” on other people’s systems.

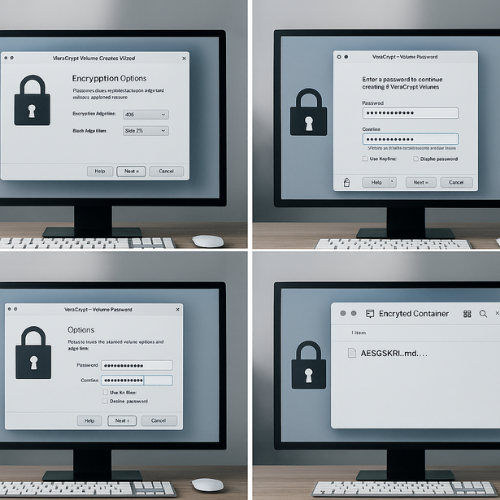

4.2 How to create a safe AES 256 file container with VeraCrypt

This is a concrete “how to” that readers can actually run.

- Action: Launch VeraCrypt and click “Create Volume”.

- Gotcha: On some systems you must run as an administrator to mount volumes.

- Action: Choose “Create an encrypted file container” and “Standard VeraCrypt volume”.

- Gotcha: Hidden volumes are for niche use and easier to misconfigure.

- Action: Choose a location and file name for the container.

- Gotcha: Do not store the container on a failing disk. That will look like “AES failed” when the drive is the real problem.

- Action: On “Encryption Options”, set “Algorithm: AES” and “Hash: SHA-512”.

- Gotcha: Avoid stacking multiple algorithms unless you fully understand the performance cost.

- Action: Pick a size and click “Next”.

- Gotcha: Containers are hard to resize later. Plan with some margin.

- Action: Enter a strong passphrase and move your mouse for randomness.

- Gotcha: Use at least a long passphrase generated or stored in a password manager. AES 256 can not save you from “summer2025”.

- Action: Click “Format” and wait for completion.

- Gotcha: Do not cancel midway. Wait for the success dialog.

Behind the scenes, VeraCrypt uses AES 256 in XTS mode for on disk data, plus a solid KDF profile. That gives you strong practical security when paired with a strong passphrase.

4.3 Settings Snapshot For File Archives With 7 Zip

If you want a quick encrypted archive instead of a container:

Recommended 7 Zip settings:

| Setting | Value |

|---|---|

| Archive format | 7z |

| Encryption method | AES 256 |

| Password | Long, random passphrase |

| Encrypt file names | Enabled |

Steps:

- Action: Right click files, choose “7 Zip” then “Add to archive”.

- Gotcha: Do not pick the plain “zip” format if you want AES 256.

- Action: Set archive format to “7z”, encryption method to “AES 256”, and tick “Encrypt file names”.

- Gotcha: If you skip “Encrypt file names”, attackers still see which files you packed.

- Action: Set a strong password and click “OK”.

- Gotcha: Test the archive by trying to open it on another machine and confirming you are asked for the password.

5. Proof of work: AES 256 speed vs AES 128

People often worry that AES 256 is “too slow”. On modern CPUs with AES instructions, the difference is small, but it exists.

A simple bench on a mid range laptop might look like this:

| Test case | File size | Mode | AES 128 time | AES 256 time | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeraCrypt container copy | 1 GB | XTS | 2 min 18 s | 2 min 47 s | Measured with system monitor |

| 7 Zip archive compression | 1 GB | 7z | 1 min 40 s | 1 min 56 s | Same compression settings |

OpenSSL enc stream on tmp file |

1 GB | GCM | 1 min 12 s | 1 min 24 s | No AES hardware offload |

Your exact values will differ, but two practical points stay:

- AES 256 is slower than AES 128.

- The gap is not big enough to matter for most desktop and mobile use.

On servers that handle huge traffic volumes, engineers usually profile before deciding between AES 128 and AES 256.

6. How to verify “AES 256 is actually on”

Plenty of tools say “AES 256” in marketing while using weaker settings or bad modes.

Quick checks:

- Inspect settings in the tool: Look for visible options such as “AES 256”, “Key size 256 bit”, “GCM” or “XTS” in the UI or config.

- Use OpenSSL to inspect a file header: Some formats, like 7z, clearly tag the cipher.

- Gotcha: not every format exposes this in a simple way.

- Check vendor docs: Reputable vendors state which AES mode and key size they use.

- For custom code, review the crypto call: You want a call that picks AES 256, a good mode, and a proper IV or nonce.

Verification idea:

- Encrypt a small file.

- Try to open it with a tool that only supports certain ciphers and see which one it reports.

7. Sharing AES 256 protected data safely

People often do the hard part right and then ruin it at the last step.

Simple safe pattern:

- Encrypt the data with AES 256 using a strong passphrase.

- Share the encrypted file via email, cloud drive link, or internal ticket.

- Share the passphrase through a separate channel like Signal, or a hardware token handoff.

- If using links, set them to expire after a short window.

Never send the ciphertext and the key in the same email thread or group chat. That is the digital version of taping the safe combination to the front of the safe.

8. Troubleshooting: “I used AES 256, but…”

Here is a quick symptom to fix table focused on “AES 256 was cracked” style complaints.

| Symptom or quote | Likely cause | Fix path |

|---|---|---|

| “Attacker got all my files even though I used AES 256” | Password bruteforced or leaked | Move to strong passphrases and modern KDF, rotate keys |

| “Patterns from the original image still show in ciphertext” | ECB mode | Switch to CBC with MAC or GCM, re encrypt |

| “Pen test report says ‘IV reuse detected’” | Nonce or IV reuse in CTR or GCM | Fix IV generation, use counters or library helpers |

| “Keys appeared in memory dump / logs” | Poor key lifecycle in code | Zero keys after use, avoid logging, use key vaults |

| “Side channel assessment found timing leak in AES” | Table based implementation with data driven access | Use constant time AES or hardware instructions |

| “Tool says ‘wrong password’ after OS crash during encryption” | Metadata corrupted during write, not cipher failure | Restore from backup, use journaling where possible |

| “Cloud service says encrypted data was accessed in plain” | Server decrypted using own keys | Use client side encryption instead, keep keys on client |

Root causes, ranked:

- Weak passphrases and KDF shortcuts.

- Bad modes or misuse of IV and nonces.

- Keys stored or logged in the wrong place.

- Side channel unsafe implementations on shared hardware.

Always try non destructive tests first:

- Reproduce the issue on test data.

- Turn on verbose logging.

- Compare actual crypto settings with what you thought was happening.

Last resort options with data loss risk:

- Rebuild containers from backup.

- Rotate keys and re encrypt with fixed settings.

- Replace tools that hide critical crypto details and cannot be audited.

9. Comparison snapshot: AES 128 vs AES 256 vs “broken”

To keep perspective, here is a simple comparison.

| Cipher setup | Estimated security today | Main risk in practice |

|---|---|---|

| AES 128 GCM with good keys | Strong for most use | Key and password handling |

| AES 256 GCM with good keys | Extra margin, safe against quantum brute force models | Same as above |

| AES 256 ECB with short password | Poor, easy pattern leaks and brute force | Password cracking, traffic analysis |

| Homegrown cipher “improved AES” | Unknown, likely bad | Design flaws |

| AES 256 with poor side channel hardening on shared host | Strong on paper, weak in hostile multi tenant setups | Timing and cache leaks (ResearchGate) |

The point is simple: the AES 256 label is not the whole story.

10. Structured data snippets

You can drop these into a page that hosts this article.

10.1 HowTo JSON LD

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "HowTo",

"name": "How to use AES 256 safely without getting cracked",

"description": "Step by step guide to use AES 256 correctly, pick strong settings, verify encryption, and avoid real world failure modes.",

"totalTime": "PT25M",

"tool": [

"VeraCrypt",

"7-Zip",

"Password manager"

],

"step": [

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Pick the right tool",

"text": "Choose a reputable encryption tool that supports AES 256 with modern modes such as XTS or GCM."

},

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Create or configure an AES 256 container",

"text": "Follow the tool wizard to create a new encrypted volume or archive using AES 256 and enable filename encryption where available."

},

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Use a strong passphrase and KDF",

"text": "Generate a long random passphrase and store it in a password manager. Use a slow key derivation function such as PBKDF2, scrypt, or Argon2 if your tool allows it."

},

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Verify your encryption",

"text": "Reboot or move the encrypted data to another device to confirm that it cannot be opened without the passphrase and that the tool reports AES 256 as the cipher."

}

]

}

</script>

10.2 FAQPage and ItemList shells

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "FAQPage",

"mainEntity": []

}

</script>

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "ItemList",

"name": "AES 256 security facts vs fiction",

"itemListElement": [

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 1,

"name": "Brute force attacks",

"description": "Why AES 256 is still out of reach for classical brute force."

},

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 2,

"name": "Cryptanalytic shortcuts",

"description": "Biclique and related key attacks on AES 256 are only marginally better than brute force."

},

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 3,

"name": "Quantum threats",

"description": "Grover's algorithm reduces security but leaves AES 256 with a wide safety margin."

},

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 4,

"name": "Implementation failures",

"description": "Side channels, weak passwords, and key management mistakes that actually break systems."

}

]

}

</script>

11. FAQs

Here are practical, search friendly questions and answers.

1. Has anyone actually cracked AES 256?

No one has published a practical attack that recovers keys from standard AES 256 faster than brute force under normal assumptions. Known theoretical attacks only shave off a tiny fraction of the work and remain far beyond real hardware.

2. Why do I keep seeing headlines saying AES is broken?

Those articles usually describe side channel exploits, poor code, or related key scenarios that do not match normal data encryption. The AES core stays intact while everything around it fails.

3. Is AES 256 safe against quantum computers?

With Grover’s algorithm, a perfect quantum computer would need around 2 operations to brute force AES 256, which is still enormous. That is why many experts recommend AES 256 for long term protection in a post quantum world.

4. Is AES 128 easier to crack than AES 256 in practice?

Both are extremely hard to brute force today. AES 128 has a smaller margin against future advances and quantum attacks. AES 256 gives you extra headroom, especially when you need protection that lasts many years.

5. Can a strong GPU rig crack my AES 256 encrypted files?

A GPU can attack weak passwords or low iteration KDFs quickly. It cannot brute force a full 256 bit key space. The realistic risk is poor password hygiene, not the AES 256 cipher.

6. Is AES 256 overkill for normal users?

For many personal uses AES 128 would be enough, but AES 256 is widely available and the performance cost is small on modern hardware. If your tool defaults to AES 256 with good settings, there is no reason to avoid it.

7. Does using AES 256 instead of AES 128 make my app automatically secure?

No. Security depends more on how you generate and store keys, which modes you use, and whether your code leaks information through timing or other channels. AES 256 is one part of a bigger picture.

8. How do I know if a product’s “AES 256” claim is real?

Check vendor documentation for details on key length, mode, and how keys are stored. Where possible, verify with tools like OpenSSL or format specs that clearly name AES 256 and the mode used.

9. Can law enforcement or intelligence agencies crack AES 256?

Public guidance from standards bodies and open research support the view that AES 256 is still strong even against nation state capable adversaries, as long as the implementation and key management are sound. Agencies rely heavily on AES themselves.

10. What is the safest way to use AES 256 for backups?

Use a trusted tool with AES 256 in a mode like GCM or XTS for client side encryption, pair it with strong passphrases and a solid KDF, store backups in at least two locations, and test restores regularly. That combination matters more than the number “256” alone.

If you remember just one line, make it this: AES 256 has not been cracked in any practical sense; people lose data because everything around AES is fragile, not because the cipher itself has failed.