Enterprise Security Policy Report: Mandatory Standards for Encrypted Client Data Lifecycle Management

This overview, provides the definitive security framework for client data lifecycle management. Client files constitute the core intellectual and professional capital of any regulated firm. The files, regardless of specific content (whether Personally Identifiable Information (PII), Protected Health Information (PHI), or proprietary commercial data), impose an inherent legal and ethical obligation for protection, demanding a defensible standard of technical and administrative due care. This report details the mandatory policy directives, cryptographic standards, and procedural controls necessary to fortify client data against internal, external, and legal threats, ensuring verifiable compliance and maximum confidentiality.

I. Strategic Imperatives and Regulatory Context

1.1. The Mandate for Confidentiality and Integrity: Defining the Duty of Care

Client files constitute the core intellectual and professional capital of any regulated firm. The files, regardless of specific content (whether Personally Identifiable Information (PII), Protected Health Information (PHI), or proprietary commercial data), impose an inherent legal and ethical obligation for protection, demanding a defensible standard of technical and administrative due care.

Establishing a robust Data Lifecycle Model (DLM) is non, negotiable for proving compliance and maintaining the duty of care. Security policy must rigorously govern five critical stages of data existence: Identification and Classification, Secure Storage (Vaults), Resilience and Backup, Secure Transfer and Key Exchange, and final Secure Disposal. Failure in any single stage constitutes a material breach of policy and potentially regulatory non, compliance.

The performance cost of strong encryption has been nullified by modern computing architecture. Contemporary processors equipped with the Advanced Encryption Standard New Instructions (AES-NI) execute AES-256 with negligible overhead, often exceeding typical storage I/O limits. Benchmarks confirm that AES-256-GCM operations achieve throughputs of 3,370.1 MB/s, and related modes such as AES-128-GCM can exceed 4,455.7 MB/s. Even generalized archive encryption using AES-256-CBC easily surpasses 1,131 MB/s. High, end systems utilizing modern solid, state drives (SSDs) in RAID configurations report BitLocker and VeraCrypt speeds exceeding 5,000 MB/s. Given that performance benchmarks demonstrate AES-256 encryption is competitive with or faster than most underlying storage throughputs, encryption must be treated as a mandatory, near, zero, overhead security feature. Consequently, any institutional decision to utilize weak or deprecated encryption standards (e.g., Zip 2.0/ZipCrypto) represents a choice to accept foreseeable, catastrophic risk for zero operational gain. This elevates the risk assessment from a discussion of technical limitations to a matter of policy negligence.

1.2. Regulatory Compliance Drivers: Mapping Technical Safeguards to Legal Requirements

Compliance with international and industry regulations forms the cornerstone of the security architecture. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) mandates specific technical safeguards that translate directly into policy requirements. These include implementing access controls, enforcing unique user identification, ensuring user authentication, utilizing audit logs and monitoring tools, and strictly requiring encryption of Protected Health Information (PHI) when it is both in transit and at rest.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) imposes stringent requirements concerning Accountability and the data subject’s Right to Erasure (Article 17). Accountability mandates that the organization must be able to demonstrate compliance through meticulous record, keeping. This necessitates detailed documentation, often maintained through a Chain of Custody (CoC), regarding the location and handling of data. The technical capacity to encrypt data and generate verifiable audit logs is foundational for fulfilling the administrative duties of conducting regular risk assessments and demonstrating overall regulatory adherence (the Accountability principle).

II. Architecture of Encrypted Data Storage (Vaults and Containers)

2.1. Cryptographic Standard Selection and Deprecation

The corporate encryption standard for all client files must be Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) with a 256, bit key length (AES-256). This selection represents the strongest version of the standard and is globally accepted as the enterprise baseline for confidentiality.

Correspondingly, all legacy and compromised encryption formats must be strictly prohibited for client data storage or transfer. Specifically, the ZIP 2.0 (ZipCrypto) encryption method is fatally compromised. Security analysts have demonstrated that this format can be cracked with off, the, shelf hacking tools, showing an 87% success rate within a few hours and a 97% success rate within a week, regardless of the password complexity. Continued use of ZipCrypto constitutes policy non, compliance and creates indefensible risk.

The recommended archival standard for client file containers is the 7z format utilizing AES-256. The 7z format offers several cryptographic advantages over ZIP-AES formats, including a more robust Key Derivation Function (KDF) implementation (discussed below), greater resistance to specialized password search tools, and fewer documented code execution vulnerabilities.

2.2. Archive Encryption (7z) vs. Full Disk Encryption (FDE/Volume)

Client data protection must employ a layered strategy utilizing both Full Disk Encryption (FDE) and granular archive containers.

FDE, encompassing tools such as VeraCrypt, BitLocker, and Apple’s FileVault, provides transparent, persistent, and passive protection for data residing on primary storage devices and workstations. Modern FDE solutions benefit heavily from specialized hardware integration. For instance, Apple Mac computers equipped with the T2 chip or Apple silicon integrate the storage directly with the Secure Enclave and the dedicated AES engine. This hardware security isolation provides a superior layer of protection for key management, mitigating side, channel attacks and securing sensitive user data even if the main kernel is compromised.

Archive containers (7z) are mandatory for two key use cases: secure data transfer to external parties and creation of granular, encrypted backups. They offer high portability across Windows, macOS (via tools like Ez7Z), and Linux environments. The high performance of both FDE and archival encryption ensures that the security feature does not impede operations. The required performance expectations, driven by hardware acceleration, are detailed in the following table.

Table 1: Hardware, Accelerated AES-256 Performance Benchmarks

| Encryption Mechanism | Hardware/Context | Operation | Throughput (MB/s) | Source Citation |

| AES-256-GCM (Cipher Mode) | Modern CPU (AES-NI) | Seal (Write) | 3,370.1 MB/s | |

| AES-128-GCM (Cipher Mode) | Modern CPU (AES-NI) | Seal (Write) | 4,455.7 MB/s | |

| 7-Zip AES-256-CBC | Modern CPU (AES-NI) | Encryption/Decryption | 1,131 MB/s | |

| TrueCrypt/BitLocker Benchmark | High, end Desktop (RAID0 SSD) | Read/Write | 5,000+ MB/s | |

| VeraCrypt Benchmark | Standard System | Read (Decryption) | 2,400 – 4,000 MB/s |

The compiled performance data confirms that AES-256 throughput far exceeds the input/output speeds of almost all standard network connections and many solid, state storage devices. This evidence mandates that encryption is adopted as a mandatory, non, optional component of data handling, without performance, based justification for using weaker ciphers.

2.3. Configuration Management: Eliminating Metadata Leakage

When creating encrypted 7z archives, a critical configuration setting must be enforced to prevent metadata leakage: the “Encrypt file names” checkbox must be explicitly selected.

File names often contain sensitive context that is equivalent to Protected Health Information (PHI) or identifying PII (e.g., “Client_Name_Settlement_Docs_2024.pdf”). If the file contents are encrypted but the file list within the archive is exposed, an adversary gains valuable reconnaissance, compromising client confidentiality and potentially violating regulatory requirements that cover all aspects of protected data, including context and metadata. This single configuration setting is a high, priority operational mandate to ensure that the archive header does not leak critical identifying information before password authentication is required.

2.4. Key Derivation Function (KDF) Rigor and Brute, Force Defense

The cryptographic strength of a password, protected container rests not just on the cipher (AES-256) but fundamentally on the Key Derivation Function (KDF). The KDF transforms the human, readable password into the cryptographic key and is engineered to incorporate a large, tunable work factor, such as a high iteration count, to make offline password guessing computationally infeasible.

The 7z format utilizes a custom KDF based on iterated SHA-256 hashing. This function is configured with a high iteration count, which has been estimated through analysis to be approximately 524,288 iterations or over 130,000 transformations. This high iteration count is the primary technical barrier against offline brute, force attacks, limiting the speed of password guesses to approximately 42.1 cycles per second in benchmark environments.

Full Disk Encryption tools offer superior KDF options. VeraCrypt, for instance, supports modern, memory, hard algorithms such as Argon2id (based on BLAKE2b) and allows configurable PBKDF2-HMAC functions. For non, system encryption, VeraCrypt defaults to 500,000 iterations, corresponding to a default Personal Iterations Multiplier (PIM) value of 485. The policy must favor Argon2id for new deployments due to its inherent resistance to specialized hardware attacks.

The deliberate disparity between the high speed of encryption (MB/s) and the extremely slow speed of KDF computation (guesses/second) establishes the security of the vault. By maximizing KDF iterations, the policy ensures that the low computational cost for legitimate users (one, time decryption upon mounting) is maintained, while the attack cost for adversaries (offline password cracking) remains prohibitively high.

2.5. Data Integrity and Resilience Protocols (Header Management)

Resilience planning for encrypted data must explicitly address the risk of cryptographic failure, distinct from standard data loss. The primary point of failure for FDE or volume containers is header corruption or loss, which renders the data volume unmountable and inaccessible.

For non, system volumes utilizing VeraCrypt, the policy must mandate regular creation and secure archival of the backup volume header via the provided utilities (Tools -> Backup Volume Header). It must be noted that restoring a volume header requires the exact password, PIM, and keyfiles that were valid when the backup was originally created. The backup header itself must be stored in a separate, secure, and auditable location, as its loss undermines the entire data recovery contingency plan.

For compressed archives, standard operating procedures must address extraction failures such as “CRC Failed”, “Data Error”, or “Unsupported Method”. Troubleshooting protocols require initial steps like malware analysis and re, downloading the file from a trusted source, followed by attempts to replace corrupted archive segments or utilize dedicated file repair utilities. This procedural readiness ensures that data integrity issues stemming from transmission errors or minor corruption can be rectified without compromising security.

III. Secure Backup and Data Resiliency Strategies

3.1. The Zero, Knowledge Requirement for Client Data Backup

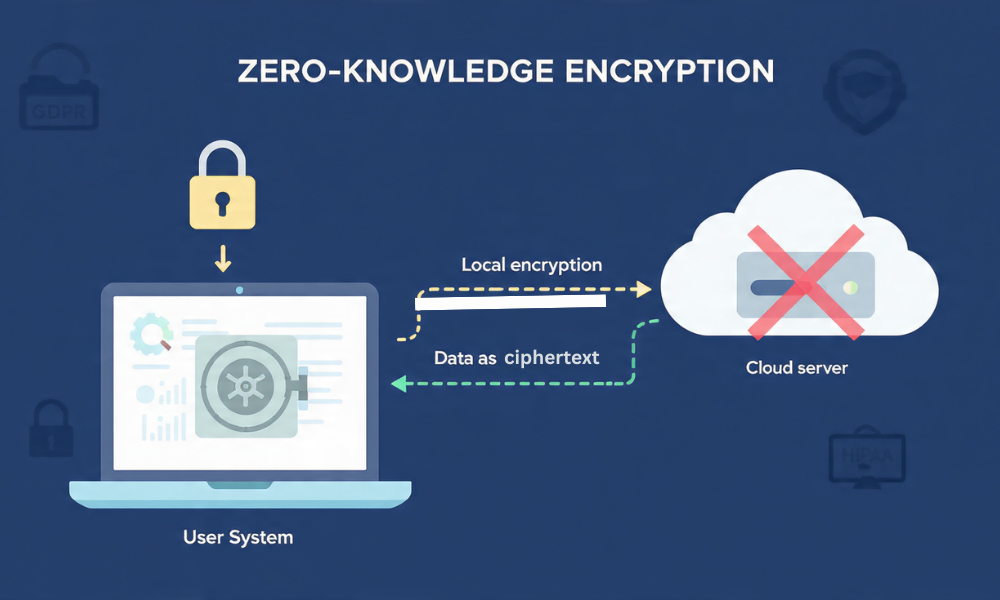

Traditional commercial cloud storage providers (e.g., Google Drive, OneDrive) operate on a provider, side encryption model, meaning the service retains the master decryption keys. This inherent design flaw exposes client data to unacceptable risks, including legal compulsion (subpoena or governmental access mandates) and compromise via internal provider breaches. For regulated client files, this level of provider authority over decryption constitutes a critical compliance risk.

The mandate for storing client file backups offsite is the utilization of Zero, Knowledge (ZK) architecture. Under the ZK model, data is encrypted client, side before transmission, and the service provider receives only the ciphertext, possessing no capacity to decrypt the data. The encryption keys remain solely under the control of the client organization.

Furthermore, selection of ZK providers must include vetting their legal jurisdiction, mitigating regulatory risks associated with foreign government surveillance or compelled access. The risk profile associated with cloud models is summarized below, reinforcing the mandatory ZK requirement for all sensitive client data.

Table 2: Cloud Storage Model Risk Assessment for Client Files

| Cloud Storage Model | Data Encryption Point | Key Custodian | Regulatory Risk Profile | Compliance Recommendation |

| Zero-Knowledge (ZK) | Client-Side | Client Organization Only | Lowest (Highest sovereignty) | Mandatory for PHI/High-Risk PII |

| End-to-End Encrypted (E2EE) | Mixed (Client/Transit/Server) | Provider/Third-party (Complex Mgmt.) | Moderate (Trust required in provider’s key system) | Suboptimal for client data |

| Traditional Cloud | Provider-Side | Provider Organization Only | Highest (Subject to subpoena, legal compulsion) | Forbidden for sensitive client data |

3.2. Backup Protocols and Encryption Efficiency

The operational flow for preparing large client files for backup must maximize efficiency while maintaining the integrity of the ZK model. Research indicates that modern multi, threaded compression algorithms, such as LZMA2 or BZIP2 within the 7z standard, significantly shrink file sizes (e.g., a virtual machine file may be compressed by nearly 50%) and are rapid, completing compression for large files in a matter of seconds to minutes.

Therefore, the optimal process flow involves performing compression before client, side AES-256 encryption. This sequence maximizes storage and network efficiency, reduces bandwidth utilization, and ensures that the final client, side encryption step maintains the required Zero, Knowledge integrity.

The organizational 3, 2, 1 backup strategy must be rigorously maintained, confirming that the “1 offsite” copy is explicitly covered by a ZK solution or is stored in a separate, high, assurance archive vault protected by FDE. Policy dictates that the priority must be cryptographic security (AES-256, 7z) over universal interoperability (Legacy ZIP). Staff training must emphasize that receiving parties require compatible tools, such as 7, Zip or Ez7Z on macOS, to successfully decrypt secure archives. This policy choice mitigates severe, systemic security risks at the cost of requiring external parties to adhere to a compatible, modern decryption process.

IV. Implementing and Maintaining the Digital Chain of Custody (CoC)

4.1. The Legal and Procedural Definition of Digital CoC

The Digital Chain of Custody (CoC) is the mandatory administrative and technical record required to prove the authenticity, integrity, and regulatory compliance of client data throughout its lifecycle. The CoC is not merely an inventory list but a detailed, real, time audit trail.

The objective of maintaining a CoC is to provide verifiable proof, a direct demonstration of Accountability, that client data has been stored, accessed, transferred, and ultimately destroyed in strict accordance with internal security policy and external regulations (e.g., HIPAA and GDPR technical and administrative safeguards).

4.2. Mandatory Audit Trail Requirements

The CoC demands exceptional logging granularity. The audit trail must meticulously document who handled the data asset, when the event occurred, where (the specific system, application, or vault path) the action took place, and what the action was (access, modification, encryption, deletion).

Technical log sources must be configured to capture this detail. At the OS and server level, Windows Event Logs must be utilized, requiring the configuration of specific auditing settings, including enabling Advanced Features within Active Directory Users and Computers and setting Object Access auditing to track success and failure events for relevant file paths and domains. This comprehensive log data is essential for tracking data access and validating media sanitization compliance for regulators.

The critical function of the audit log is its role as a liability shield. In the event of a breach investigation or regulatory audit, the audit logs are the only technical evidence capable of demonstrating that internal access was controlled, systems were monitored, and policy was enforced. A lack of logging or the presence of a “dark period” where logs are missing constitutes a catastrophic failure of the CoC and leads regulators to conclude that administrative safeguards were inadequate.

4.3. Access Control and Segregation of Duties

The Principle of Least Privilege must govern all access to client file vaults. Access must be strictly restricted based on the employee’s role, the necessity of the access, and predefined system permissions. Furthermore, administrative procedures must ensure the immediate removal and revocation of access for any departing employees. This revocation must encompass immediate disabling of system credentials (e.g., Active Directory accounts) and immediate invalidation or revocation of any shared archive passwords or keyfiles.

Table 3: Technical Implementation of Auditable Chain of Custody (CoC)

| CoC Stage | Required Action/Event | Required Documentation (Audit Log) | Compliance Linkage |

| Ingestion | File is moved to secure vault and encrypted. | Encryption parameters (AES-256), Handler ID, Vault Path, Timestamp. | PHI/PII Encryption, Integrity |

| Active Access | Vault is decrypted/mounted for use by authorized personnel. | User authentication success/failure, Start/End time of mount, Files accessed. | Access Control, Accountability |

| Transfer | File/Archive is securely transmitted (e.g., via ZK portal). | Recipient ID, Proof of E2E encryption applied, Confirmation of receipt. | Security in Transit, Accountability |

| Disaster Recovery | Header is restored or key is utilized for backup retrieval. | Header restoration log, Key ID used, Restoration success/failure. | Contingency Plan Testing, Integrity |

V. Secure Key and Password Management

5.1. Standards for High-Entropy Passphrases

Despite the strength of AES-256 and high KDF iteration counts, the security of the vault remains dependent on the entropy of the user, defined password. Organizational policy must enforce high, entropy passphrases, requiring a minimum length exceeding eight characters and incorporating a mixture of uppercase letters, lowercase letters, and numerals.

Personnel must understand the interplay between password entropy and KDF defense. The KDF’s multi, iteration barrier (e.g., 500,000 steps) drastically reduces the rate at which an attacker can test passwords. However, if the initial password possesses low entropy (i.e., it is short or predictable), the small key space can still be searched relatively quickly, defeating the protection offered by the high iteration count. Therefore, the policy mandates that employees generate and use passphrases of maximal length and complexity to leverage the full technical defense provided by the KDF.

5.2. Secure Password Sharing Protocols

Given that AES-256 encryption is practically unbreakable, the greatest vulnerability lies in the human transfer of the password or key. Insecure communication channels (email, non, secure messaging) are strictly prohibited for password exchange.

The mandatory protocol for externally sharing archive passwords with clients or partners must utilize ephemeral, secured, one, time secret exchange links. These services generate a link that permits the recipient to view the secret only once, after which the secret is permanently and irretrievably deleted, transforming a high, risk procedural weakness into a technical safeguard.

For sensitive internal key material transfers, or for establishing automated shared secrets between systems, the use of modern authenticated key exchange protocols is required. Protocols such as X3DH (Extended Diffie, Hellman) or PQXDH (Post, Quantum Extended Diffie, Hellman) establish a shared secret key between two mutually authenticated parties, ensuring essential properties such as forward secrecy and cryptographic deniability.

VI. Data Disposition and Compliance (Right to Erasure)

6.1. Procedures for Comprehensive Data Deletion

Data disposition must comply with the GDPR Right to Erasure, necessitating a process for the verifiable, secure, and permanent deletion of data that is no longer necessary for the purposes for which it was collected or processed.

The foundational requirement is the accurate location of all data copies. The organization must utilize the Chain of Custody (CoC) inventory to identify every instance of the client data, spanning primary storage, live backups, ZK cold archives, and any temporary transfer locations, to ensure comprehensive erasure.

All erasure requests must be managed through a formal process designed to confirm the identity of the requester and verify whether the data falls under any regulatory or legal exemptions. GDPR explicitly allows retention if the data is required for legal or regulatory compliance (e.g., tax records) or for the establishment, exercise, or defense of legal claims.

6.2. Secure Sanitization Techniques

The preferred method for secure sanitization of data residing within encrypted containers (FDE or VeraCrypt volumes) is cryptographic erasure. This technique involves the instantaneous and verifiable destruction of the encryption keys used to protect the data. Since the ciphertext is rendered permanently inaccessible without the keys, cryptographic erasure achieves the same security result as physical destruction but with greater speed and efficiency.

For media that was never protected by FDE or where cryptographic erasure is not possible (e.g., legacy physical backups), physical destruction (shredding or degaussing) is required, followed by the acquisition of a certified destruction certificate. All sanitization procedures must be preceded by a malware scan to ensure no data is being encrypted or deleted in a manner that obscures an underlying breach.

6.3. CoC Documentation for Final Disposal

The Chain of Custody for a data asset is only formally concluded upon verifiable destruction. The final documentation required to satisfy the Right to Erasure must be rigorously auditable. This log entry must detail the specific method of sanitization, the exact date and time of erasure, and the identification of the personnel responsible for executing the destruction. The creation of an authenticated disposal log is crucial because it represents the ultimate proof of compliance. Without this detailed, auditable documentation, the firm remains perpetually liable for data that could theoretically still reside in an untracked or unsanitized repository. The CoC must therefore strictly enforce the capture and secure archival of these destruction certificates and erasure logs to formally terminate organizational liability.

VII. Frequently Asked Questions

Is AES-256 truly uncrackable by brute force?

Yes. AES-256 uses a 256, bit key, requiring an estimated trillions of years for an average brute, force attack to succeed, ensuring its cryptographic integrity is sound against current computational capabilities. Security failures almost always stem from poor key management or implementation errors, not the algorithm itself.

Why is my web browser complaining about “Mixed Content” when I use HTTPS?

A Mixed Content warning occurs when a primary page is loaded securely over HTTPS, but some linked resources (e.g., images, scripts, or fonts) are called insecurely over HTTP. Browsers block or warn about this to prevent man, in, the, middle attacks, removing the secure padlock icon in the process.

What does “Perfect Forward Secrecy” protect me from?

Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS) ensures that if an attacker compromises a server’s long, term private key in the future, they still cannot decrypt any secure sessions that they may have previously recorded. It achieves this by ensuring that every session uses unique, temporary, and unrecoverable session keys.

Why is ChaCha20 sometimes preferred over AES-256 in high, speed protocols?

ChaCha20 is highly efficient in software, only contexts and general CPUs, making it ideal for low, latency network protocols like TLS 1.3. AES-256 is typically preferred for disk encryption where hardware acceleration (AES-NI) is available.

How do I check a website’s SSL certificate validity in Chrome or Firefox?

In Chrome, click the three, dot menu > More Tools > Developer Tools > Security tab, then click “View Certificate”. In Firefox, this information is found under Preferences > Advanced > Certificates tab > View Certificates.

I lost my encrypted USB drive. Can I recover the files without the password?

No. The file data on encrypted volumes (such as those protected by BitLocker or VeraCrypt) is mathematically inaccessible without the necessary decryption key or password, emphasizing the importance of secure key backup.

Is it legal to use screen recording software to bypass the black screen?

Recording DRM, protected content for private, non, commercial use, such as personal study or educational presentations, is often viewed as acceptable under principles like fair use. However, unauthorized redistribution, uploading, or selling of that content is illegal and violates the service’s Terms of Service.

Why does ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography) allow for shorter keys than RSA?

ECC provides a greater cryptographic strength for an equivalent key size compared to RSA because its underlying mathematical problem is harder to solve. This means a shorter ECC key (e.g., 256 bits) can provide security equivalent to a much longer RSA key (e.g., 3072 bits), leading to smaller file sizes and faster processing.

What specific risks do employees’ personal USB drives pose to a corporate network?

Personal drives pose risks including malware infection (due to use on unsecured home PCs), data exfiltration of corporate secrets, and violation of software licensing agreements through the unauthorized transfer of unlicensed software (Shadow IT).

What is the practical difference in speed between symmetric and asymmetric encryption?

Symmetric ciphers (AES, ChaCha20) are optimized for speed, often operating at speeds measured in gigabits per second for bulk data. Asymmetric ciphers (RSA, ECC) are significantly slower, often performing at only kilobits per second, making them suitable only for small tasks like key exchange.

How is the memory cost parameter (m) in Argon2id critical for security?

The memory cost parameter (m) requires an attacker to commit significant, non, cacheable amounts of RAM during the cracking process. This memory requirement significantly increases the capital investment and operating costs required to launch parallel cracking efforts.

What does a Widevine L1 requirement mean for my device?

Widevine L1 means the content provider requires the decryption key and video stream to be handled exclusively within a secure, dedicated hardware environment (GPU/SOC) that prevents the operating system from accessing the decrypted video data, thus enabling high, definition playback (1080p and 4K).

Why do I need to dismount my VeraCrypt volume before ejecting the USB?

Proper dismounting is required to signal to the operating system that the virtual volume connection is closed. Failing to dismount a VeraCrypt volume can lead to file corruption or data loss if the USB drive is removed while the system still holds cached data or file handles open.

Why is using a VPN sometimes cited as a cause for DRM errors?

DRM systems often use geo, blocking to ensure content is only played in licensed regions. If a VPN changes the user’s apparent IP address to a region not covered by the content license, the DRM license check will fail, resulting in a geo, blocking error.

If my application uses a proprietary file locking mechanism like USB Secure or Folder Protect, does that replace AES-256 encryption?

No. Proprietary file locking mechanisms (such as those offered by products like File Lock Pro) are primarily interfaces for access management and file visibility control. The actual data protection usually relies on robust, internationally recognized encryption standards like AES-256 for the critical byte, by, byte ciphering.

VIII. Conclusions and Directives

The analysis confirms that the technological impediments to high, security data management have been virtually eliminated by hardware, accelerated encryption. Consequently, organizational security posture is now exclusively determined by adherence to policy rigor and configuration management standards.

Key Directives for Enterprise Policy:

- Mandatory AES-256 and 7z Standard: All client files must be encrypted using AES-256, utilizing the 7z archive format for transfer and granular sharing. Use of legacy formats (e.g., ZIP 2.0/ZipCrypto) is prohibited and classified as policy non, compliance.

- Zero, Knowledge Backup Mandate: All offsite client data backups must be conducted using Zero, Knowledge cloud providers, ensuring the firm retains exclusive control of the decryption keys and vetting provider jurisdiction for sovereignty compliance.

- CoC Audit Requirement: A comprehensive Digital Chain of Custody must be implemented, requiring high, granularity audit logging (Who, When, Where, What) of all data access and handling events, utilizing Windows Event Logs and application, level logging to demonstrate accountability and defend the firm’s security posture.

- Configuration Enforcement: All archive creation must explicitly enforce the “Encrypt file names” setting to prevent metadata leakage, recognizing that file names themselves often contain PII or confidential information.

- Secure Key Exchange: Internal and external sharing of passwords must be conducted exclusively via ephemeral, one, time secret links or authenticated cryptographic exchange protocols (X3DH/PQXDH) to mitigate the human factor as the weakest link in the security chain.

- Verifiable Disposal: Data disposition must follow a process that utilizes the CoC to locate all copies and concludes with cryptographic erasure or physical destruction, documented by a final, auditable destruction certificate, fulfilling the GDPR Right to Erasure.