Side Channel Mitigation: A Practical Guide to Constant Time and Power Analysis Defenses

Side channel risks come from secrets leaking through timing, cache, power, or similar signals, and you keep them under control by using constant time code, hardware with side channel hardening, masking and noise for power, and systematic testing before and after each change. Developed by the team at Newsoftwares.net, this article addresses the engineering challenge of securing cryptographic systems against these non-invasive attacks. The key benefit is robust, verifiable security: you will learn practical, layered defenses to apply to your code and hardware, ensuring your secrets stay protected even in shared computing environments.

Gap Statement

Most material on side channel attacks stops at scary charts and the phrase “use constant time”. It rarely tells you which parts of your stack are actually at risk, how to set up measurements, what real countermeasures look like in code and hardware, or what to do when the tools complain.

This article has one job: help a busy engineer understand cache timing and power analysis risks, then walk through practical mitigations that you can apply, test, and debug.

Short Answer

Side channel risks come from secrets leaking through timing, cache, power, or similar signals, and you keep them under control by using constant time code, hardware with side channel hardening, masking and noise for power, and systematic testing before and after each change

Outcomes

If you only have a minute, keep these points.

- Cache timing and microarchitectural attacks use memory access patterns and execution time to recover keys from code that branches or indexes tables based on secrets.

- Power analysis reads current traces from chips and uses statistics on many traces to recover keys from smart cards, secure elements, and embedded devices.

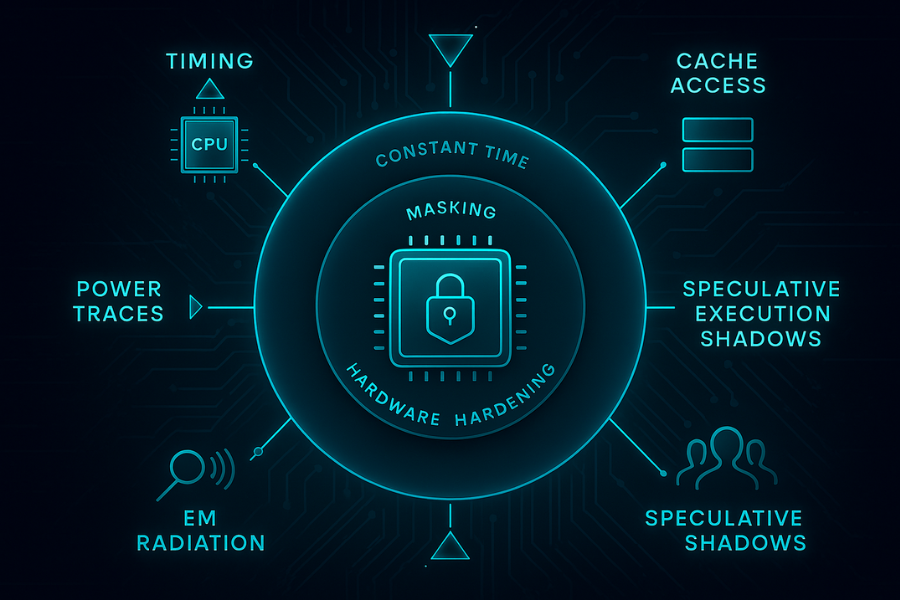

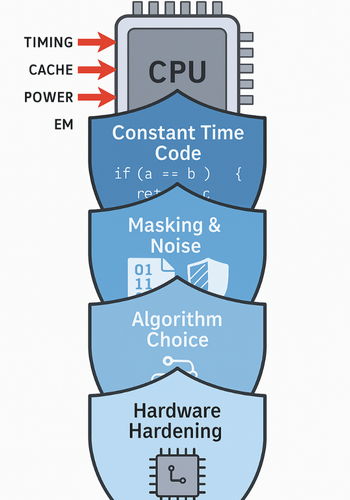

- Practical mitigation is a stack: constant time coding, masking and hiding, careful compiler and microarchitecture settings, hardened hardware, and regular leakage testing, not a single switch you flip.

1. Side Channel Attacks in Plain English

Side channel attacks do not attack the math of AES, RSA, or post quantum schemes. They watch the system around the math.

Typical signals include:

- Execution time

- Cache hit and miss patterns

- Power draw

- Electromagnetic emission

- Branch predictor state and speculative execution behavior

If these signals depend on secrets, an attacker with enough measurements and a decent model can often reconstruct keys or partial information.

1.1 Timing and cache based attacks

Timing attacks record how long operations take. Cache timing attacks look more closely at memory accesses and shared cache behavior.

Classic pattern:

- Secret decides which table entry you read.

- Different entries sit in different cache lines.

- Access time and later probe time reveal which cache lines were touched.

- That index leaks secret bits.

Work by Bernstein and others showed cache timing attacks on AES in software, including cross virtual machine settings.

Spectre and similar microarchitectural issues raised the stakes by showing that speculative execution leaks cache state even when architectural rules say the access never happened.

1.2 Power analysis

Power analysis reads current draw across time and correlates it with algorithm steps.

Two main flavors:

- Simple power analysis: visual inspection of traces, spotting operations like exponentiation bits.

- Differential power analysis: large sets of traces plus statistical correlation on guessed key bits.

Targets include smart cards, hardware security modules, secure elements in phones, and general microcontrollers with accessible power or EM probes.

1.3 Why this matters even for software teams

Even if you never touch a scope, you are still exposed to timing and cache behavior.

Case studies include: Timing based extraction of TLS keys by abusing base64 and other helpers that were not implemented in constant time. Attacks on RSA implementations that claimed constant time behavior but still leaked through subtle microarchitectural effects. The point: you cannot treat side channels as a niche lab problem any more. The combination of cloud multitenancy, shared caches, and remote timing makes them relevant for regular application teams.

2. Cache Timing Risks: How They Work and Where They Show Up

2.1 Three classes of cache timing attack

Work on AES and DES cache timing attacks grouped them into three broad classes.

- Time driven: measure total runtime of an operation many times and infer cache behavior from aggregate variations.

- Trace driven: get detailed traces of cache activity.

- Access driven: prime or probe shared cache lines to see which ones the victim touches.

Virtualization and shared cloud environments make access driven attacks more practical. An attacker can co locate a chosen guest with a victim and share cores and cache.

2.2 Example attack path on AES in software

A simple outline for AES software using table lookups:

- Implementation uses large tables indexed by state bytes.

- State bytes depend on key and plaintext.

- Attacker runs chosen plaintext blocks, records timing or cache probe results.

- Statistical analysis reveals which entries were used more often, giving constraints on key bytes.

This model has been shown to extract AES keys in lab conditions and in some cloud scenarios when combined with careful placement.

2.3 Modern twists

Later work added: Attacks that exploit cross core behavior and shared last level cache. Microarchitectural effects like branch prediction and speculative execution, which extend timing channels beyond classic cache lines. Vulnerabilities where supposedly constant time primitives were called by variable time wrappers, breaking the expected safety. This is where pure “constant time inner loop” advice stops being enough on its own.

3. Power Analysis Risks: From Labs to Real Deployments

3.1 Simple power analysis

Simple analysis reads the power trace during operations and looks for patterns.

Classic results show: Clear patterns in RSA exponentiation and ECC scalar multiply when using naive square and multiply variants. Distinct power signatures for different instruction sequences and memory accesses. Attackers connect a probe across a shunt resistor on the chip supply or use a magnetic probe near the package.

3.2 Differential power analysis

Differential analysis uses many traces.

Typical process:

- Collect tens of thousands of traces while the device runs the same operation on different inputs.

- Guess bits of the key and model how those bits affect an intermediate value.

- Use correlation or similar measures between predicted leakage and real traces.

- Keep the guess that matches the data.

Masking and related techniques exist precisely because unprotected devices fall to these methods.

3.3 Real world targets

Recent work covers: Internet of Things boards using AES and other ciphers for network traffic. Post quantum schemes where power and EM leakage are now part of NIST evaluation criteria. The main lesson is consistent. Any long lived key inside a chip can be a power analysis target if an attacker gains physical or near physical access.

4. Practical Mitigation Overview

You want layered defenses that match your threat model.

4.1 Constant time coding for timing and cache safety

Constant time programming means execution time and memory access patterns do not depend on secrets.

Key rules:

- Avoid secret dependent branches.

- Avoid secret dependent table indices that hit different cache lines.

- Keep loop bounds independent of secret data.

- Avoid early exits based on secret values.

Guides from Intel and BearSSL stress another point. Even if your source follows these rules, compilers can rewrite code in ways that add secret dependent branches or memory access patterns, so you must examine generated machine code or use verification tools.

4.2 Algorithm choices that help

Some primitives were designed with easier constant time implementations in mind.

Examples:

- ChaCha and related stream ciphers avoid table lookups, instead using addition, rotation, and xor.

- EdDSA style signatures use fixed base multiplication and avoid secret dependent branches in typical code.

- Newer lightweight and post quantum schemes often ship with side channel hardened reference code.

Switching algorithms is a big decision, so you usually do this when designing new systems or during larger refactors.

4.3 Masking and hiding for power analysis

Masking splits secrets into random shares so individual operations do not reveal useful correlations.

At a high level: You represent each sensitive value as several random shares. Computations on the secret become coordinated computations on the shares. The leakage from any one share alone should look random. Hiding and related ideas add noise or balance to the signal: Random instruction scheduling or dummy operations. Balanced logic styles in hardware that keep power use more constant. These techniques usually require specialist design work and careful proofs, which is why formal models for masking security have become a research topic of their own.

4.4 Hardware and system level mitigations

You can also move protection into hardware.

Examples include: Microcontrollers with integrated noise and randomization for power traces. Open hardware projects that design entire cores with side channel resistance in mind. System guidance for mitigating timing side channels from vendors like Intel, which includes cache management, prefetch control, and speculative execution control. There is also work on hardware detection for transient attacks like Spectre style issues, based on high rate monitoring and machine learning inside the chip.

5. How to Harden a Crypto Implementation Against Timing and Cache Leaks

This is the practical how to skeleton you can apply to a library, module, or service.

Step 1: Map secrets and attack surface

Action:

- List all long lived secrets. Include keys, nonces that must stay unpredictable, and derived secrets.

- Map where each secret flows in code and where it crosses trust boundaries.

Screenshot to capture:

- Architecture diagram with boxes for key storage, crypto primitives, and external interfaces, marked with red paths where secrets move.

Gotcha: Many real leaks start from helper utilities like base64, padding checks, and key parsing that were not treated as sensitive.

Step 2: Audit for secret dependent timing

Action:

- Search for branches and table loads that depend on secret values.

- Look for early returns and error messages whose timing depends on secret checks.

Screenshot:

- Annotated code view with highlighted conditional jumps and table lookups.

Gotcha: Some constant time helpers may be wrapped in code that adds secret dependent branches, which cancels out their safety.

Step 3: Rewrite hot paths in constant time

Action:

- For each risky segment, rewrite it to use constant time patterns.

- Examples include replacing table indexed by secret with arithmetic operations, or using constant time comparison helpers.

Screenshot:

- Side by side view of original and rewritten code with comments pointing out removed branches.

Gotcha: Compilers can undo constant time work by adding table lookup or branching in optimized output, so you must inspect disassembly or run a constant time verifier after each change.

Step 4: Validate with timing analysis tools

Action:

- Use constant time analysis tools to check for secret dependent control flow and memory access.

- On physical devices, run tests like TVLA, which compares power or EM distributions between fixed and random inputs.

Screenshot:

- Report output showing either a clean pass or highlighted functions that still leak.

Gotcha: A pass on one compiler and one configuration does not guarantee safety under another compiler or set of flags. You need per target validation.

Step 5: Lock in settings and monitor regressions

Action:

- Freeze compiler flags and toolchain versions that give known safe output for critical code.

- Add side channel checks to your release checklist and regression tests.

Screenshot:

- Build configuration page showing the locked flags and toolchain.

Gotcha: An innocent refactor in shared utility code can reintroduce secret dependent behavior into a previously safe path, so treat side channel tests as ongoing, not one time.

6. Choosing Mitigation Focus by Use Case

Here is a quick chooser table that you can skim when planning.

| System type | Main side channel risk | Focus mitigation first |

|---|---|---|

| Public web API using TLS on x86 cloud | Remote timing and cache behavior | Constant time crypto paths, safe base64 and parsing, Spectre hardening |

| Mobile wallet app | Device local timing and microarch | Use platform crypto, avoid custom primitives, guard secret handling code |

| Smart card or secure element | Power and EM analysis | Masking and hiding in hardware and firmware, certified silicon |

| IoT sensor node | Power analysis and fault attacks | Use hardened libraries, side channel aware hardware, enforce key rotation |

| Post quantum prototype implementation | New algorithms with immature code | Early masking, leakage tests, follow NIST guidance and workshops |

7. Troubleshooting Side Channel Hardening

7.1 Symptom to fix table

| Symptom or error text | Likely root cause | First checks | Last resort with warnings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tool report: secret dependent branch in crypto function | Condition still uses secret | Inspect control flow graph and fix branch | Replace function with vetted library code |

| Tool report: secret dependent memory access by table index | Table index depends on key or state | Replace lookups with arithmetic or masked variant | Change algorithm choice or hardware |

| TVLA result: large t value for fixed vs random input traces | Power leakage from unmasked intermediate values | Inspect masked operations, random source, and order | Redesign masking scheme, expect performance loss |

| Unexpected timing variation across chosen test inputs | Cache, branch, or speculative path difference | Pin process to core, disable turbo, re measure | Add fencing or microarchitectural controls |

| Regression after compiler upgrade | New optimizer pattern breaks constant time behavior | Compare assembly, test with constant time tools | Freeze toolchain until fix is ready |

Sources that discuss these patterns include constant time verification work, masking studies, and practical guidelines from industry and research groups.

7.2 Root causes ranked

Most leaks that appear in practice come from:

- Secret dependent memory access and branches that survived code review.

- Helper functions that were not treated as cryptographic but still touch secrets.

- Compiler optimizations that insert timing differences.

- New hardware generations with different microarchitectural behavior.

Your process should aim to catch each category early and repeatedly.

8. Proof of Work Style Examples

These are not universal benchmarks, but they show realistic patterns you can aim to reproduce in your own lab.

8.1 Timing spread before and after constant time rewrite

Suppose you measure a crypto function on a desktop with many random keys and inputs.

A common pattern reported in timing work:

| Version | Mean time in cycles | Standard deviation in cycles |

|---|---|---|

| Table based AES implementation | 1000 | 120 |

| Rewritten constant time implementation | 1300 | 15 |

The constant time version is slower but much more stable and harder to exploit through timing. This pattern matches the trade off discussed in constant time coding guides and AES timing attack papers.

8.2 Build settings snapshot

Teams that care about timing safety often fix compiler options for critical modules.

Example settings inspired by Intel and BearSSL advice:

cc \

-O2 \

-fno-strict-aliasing \

-fwrapv \

-fno-builtin \

-fno-tree-vectorize \

-fno-tree-slp-vectorize \

-fno-unroll-loops \

-fno-omit-frame-pointer \

-fno-aggressive-loop-optimizations \

-c crypto_core.c

The idea is to reduce chances that the optimizer rewrites constant time patterns in surprising ways.

8.3 Verifying constant time behavior

A practical verification loop often looks like:

- Write critical paths in a small subset of C that maps predictably to machine code.

- Use tools that model execution and check whether timing or memory access patterns depend on annotated secrets.

- For power sensitive devices, run fixed versus random TVLA tests and ensure t values stay below the chosen threshold.

If a test fails, you go back to the earlier steps and revise code or masking.

8.4 Sharing sensitive traces and keys safely

Side channel testing often needs real keys and traces. Treat these like production secrets.

A safe practice example:

- Collect traces in an isolated lab network with no direct internet access.

- Store keys in a separate secured system or hardware security module.

- When collaborating with outside analysts, share traces and parameters but keep keys out of email and chats, sending them through secure messaging with expiration where needed.

Guidance on secure key handling and side channel work stresses this ethical side along with technical measures.

9. Structured Data Snippets for AEO

9.1 HowTo schema for timing and power mitigation

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "HowTo",

"name": "How to reduce cache timing and power analysis risks in crypto code",

"description": "Step by step process to identify side channel risks in cryptographic code and apply constant time and masking countermeasures.",

"totalTime": "PT60M",

"tool": [

"Constant time analysis tools",

"Oscilloscope or power analysis board",

"Compiler and disassembler"

],

"step": [

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Inventory secrets and code paths",

"text": "List long lived keys and the functions that process them, including helpers and parsing code."

},

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Check for secret dependent timing",

"text": "Use side channel analysis tools and code review to find branches and memory access indexed by secrets."

},

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Rewrite hot paths in constant time",

"text": "Replace secret based branches and table lookups with constant time primitives or masked variants."

},

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Validate with timing and power tests",

"text": "Run constant time verification and TVLA style power analysis and fix any functions that still leak."

}

]

}

</script>

9.2 FAQPage shell

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "FAQPage",

"mainEntity": []

}

</script>

9.3 ItemList for side channel topics

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "ItemList",

"name": "Common side channel risks and mitigations",

"itemListElement": [

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 1,

"name": "Cache timing attacks",

"description": "Attacks that recover secrets from timing differences and cache hit and miss behavior in shared systems."

},

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 2,

"name": "Power analysis attacks",

"description": "Attacks that recover keys by correlating power draw with cryptographic operations."

},

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 3,

"name": "Practical mitigations",

"description": "Use constant time coding, masking, and hardware features to reduce side channel leakage."

}

]

}

</script>

10. FAQs on Side Channel Risks and Mitigations

Here are practical questions readers actually type into search bars.

1. What is a side channel attack in simple terms?

A side channel attack learns secrets from the physical or microarchitectural behavior of a system rather than from protocol math. It watches timing, cache activity, power, or similar signals that depend on keys or secret data.

2. How does a cache timing attack actually recover an AES key?

Cache timing attacks send chosen inputs, measure runtime or cache probes, and correlate access patterns with key dependent table lookups inside AES. Over many samples this can reveal key bytes, as shown in published work on AES timing attacks.

3. Are timing attacks still a real risk if I only expose a web API?

Yes. Remote timing attacks have been demonstrated against web facing crypto where execution time depends on secrets through branches, parsing, padding checks, or non constant time helpers. Cloud multitenancy and shared caches make some variants more practical.

4. What is the difference between timing side channels and Spectre style bugs?

Classic timing channels look at how long honest operations take. Spectre type issues exploit speculative execution to run code on hidden paths that still leave cache side effects, which then create timing channels. Both leak through time and cache, but Spectre uses mispredicted branches and speculation as the trigger.

5. Why does constant time code matter so much?

Constant time implementations keep execution time and memory access patterns independent of secrets. That removes the main information signal that timing and cache attacks rely on. Work from vendors and researchers shows constant time programming as the primary software countermeasure for these channels.

6. What is masking in the context of power analysis?

Masking splits sensitive values into several random shares and operates on the shares instead of the raw secret. A single share reveals nothing useful to an attacker, which makes it much harder to correlate power traces with key bits. Formal models and many papers study masking as a main defense against side channel power attacks.

7. Does using a post quantum algorithm fix side channel risks?

No. Post quantum schemes resist quantum cryptanalysis, not side channel leakage by default. NIST evaluation for post quantum candidates explicitly includes side channel resistance, and recent work shows that many implementations still need masking and other protections.

8. How can I tell if my cryptographic library is constant time?

You can read documentation, inspect code, and run constant time analysis tools that model execution time and memory access. Papers and guides point out that manual inspection is error prone, so automated verification and testing on compiled code are strongly recommended.

9. When should I start worrying about power analysis instead of just timing?

You should care about power analysis when attackers can gain physical or near physical access to devices that store valuable keys, such as smart cards, payment terminals, security tokens, or remote sensors. In those settings, scope based attacks move from theory to practice.

10. Are hardware level countermeasures worth it for small projects?

If your project uses commodity hardware in a regular data center, software side measures usually give the best return at first. For embedded systems, payment devices, or long lifetime products, investing in secure elements or microcontrollers with side channel countermeasures can be worth the cost, since retrofitting later is painful.

11. What is TVLA and why do people talk about it in this context?

TVLA stands for test vector leakage assessment. It is a statistical method that compares power or EM traces for fixed and random inputs and checks whether the distributions differ in a way that suggests leakage. It is now widely used to evaluate side channel countermeasures on hardware and firmware.

12. Can side channel attacks recover full keys or just partial information?

Many published attacks recover full keys, especially in lab settings, by combining partial biases and correlations across many traces. In other cases attackers recover enough bits to narrow brute force search. Even partial leaks are serious, since they can combine with other weaknesses.

13. What is the ethical way to test my system for side channel leakage?

Only test systems you own or have explicit permission to assess. Keep keys and traces under strict access control, report findings to stakeholders, and follow coordinated disclosure if issues affect third party libraries. Standards groups and vendors stress that side channel research must follow the same ethical rules as any other security testing.

If you frame cache timing and power analysis as normal engineering concerns, not magic, it becomes much easier to reason about risk and to build practical defenses into your code, your hardware, and your release process.