The Integrated Defense Architecture: Fortifying Data Transit, Access, and Storage

This executive guide, created by the security experts at Newsoftwares.net, provides the definitive framework for modern data protection. The modern digital ecosystem requires an integrated defense strategy that begins with a clear understanding of network encryption boundaries. The analysis confirms four key mandates for any organization seeking to establish state, of, the, art security, a strategy that moves beyond simple compliance to verifiable security and sustained confidentiality.

I. Beyond the Padlock: Unmasking Network Security (TLS vs. E2EE)

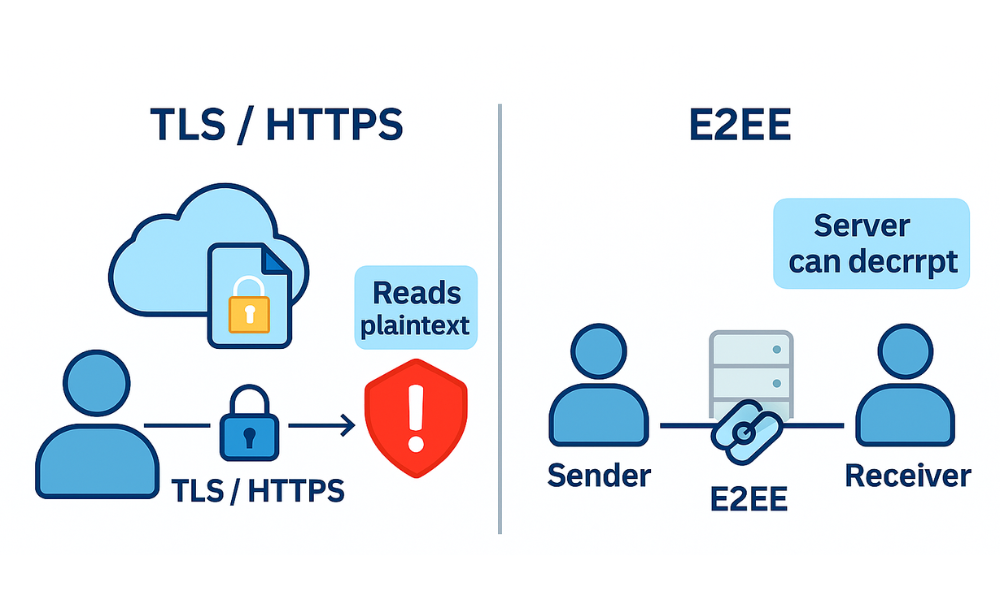

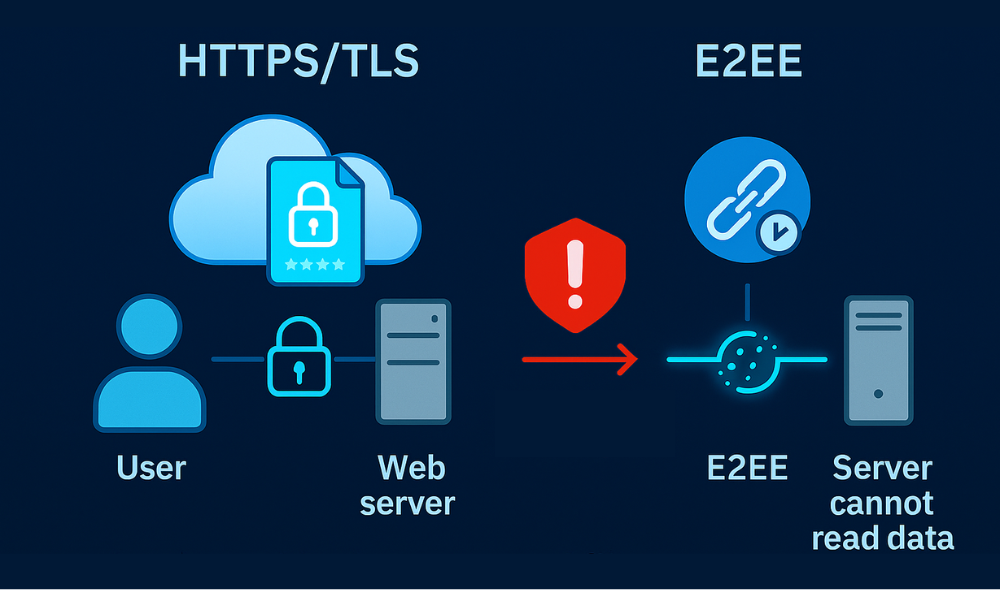

The modern digital ecosystem requires an integrated defense strategy that begins with a clear understanding of network encryption boundaries. Many users rely implicitly on the padlock icon in their browser, believing it signals complete privacy. However, a deeper analysis reveals that Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) is a critical, but fundamentally limited, layer of defense.

The Critical Distinction: Why HTTPS Fails the Privacy Test

HTTPS is simply the standard HTTP protocol layered on top of TLS (Transport Layer Security). When a connection is made, a complex cryptographic negotiation occurs, encrypting data between the client (your browser) and the immediate web server. This is known as transport, level security. This connection shields data from interception by local network snoopers or the internet service provider.

The central point of vulnerability in HTTPS is the trust model: the server, which manages the long, term private key, possesses the ability to decrypt the entire message stream into plaintext. This means that the service provider itself, the company owning the server, is a plaintext intermediary. If that server is compromised, or if the provider is compelled by law enforcement to surrender data, the communications are exposed. While the padlock indicates a secure connection, it does not guarantee the website itself is secure or trustworthy.

End-to-End Encryption (E2EE) establishes a completely different trust model. With E2EE, data is encrypted on the sender’s device and remains encrypted as undecipherable ciphertext while traveling through the service provider’s network. Decryption occurs only on the intended recipient’s device. The service provider’s servers merely relay scrambled data and do not possess the necessary key to read the content. This architectural shift is why E2EE protocols, such as those used by Signal or WhatsApp, move beyond mere compliance to true user privacy guarantees by deliberately removing the service provider from the chain of trust.

Key Differences: Transport Layer Security (HTTPS) vs. End-to-End Encryption (E2EE)

| Feature | HTTPS/TLS (Transport Security) | E2EE (End-to-End Encryption) |

| Encryption Scope | Client to immediate Server only (transport, level). | Client to Client (Recipient) only. |

| Server Access to Data | Server can decrypt and read plaintext. | Server relays encrypted ciphertext, cannot decrypt. |

| Key Management | Server manages long, term private key (CA verified). | Keys generated and stored locally on endpoints. |

| Security Risk | Requires implicit trust in the server operator. | Protected even if the server is compromised or subpoenaed. |

The Mechanics of Trust: Decoding the TLS Handshake

The TLS handshake is the foundational process that establishes a secure session before any application data is exchanged. It is a critical negotiation that verifies identity, agrees on encryption protocols, and securely generates temporary keys.

Detailed Breakdown of the 4, Step Process

The TLS handshake comprises a series of datagrams transferred between the client and server. The specific sequence can differ based on the key exchange algorithm chosen, particularly between TLS 1.2 and the more streamlined TLS 1.3.

- Step 1: The ‘Client Hello’ Message

Action: The client initiates the process by sending a ‘hello’ message. This message contains the highest TLS version the client supports, a list of cipher suites it is willing to use (e.g., combinations of AES-256 and key exchange methods), and a random string of bytes known as the “client random”. In TLS 1.3, clients often send ephemeral key shares for algorithms like Elliptic Curve Diffie, Hellman (ECDHE) immediately in this first message to reduce latency.

- Step 2: The ‘Server Hello’ Message

Action: The server replies by selecting the best, matching TLS version and the preferred cipher suite from the client’s list. Crucially, the server sends back its SSL certificate and the “server random” string generated by the server.

- Step 3: Authentication and Key Exchange

Action: The client authenticates the server by verifying the SSL certificate. This involves checking two main criteria: ensuring the certificate is signed by a trusted Certificate Authority (CA) and confirming that the domain name matches the certificate. If this verification succeeds, the client and server execute a key exchange, such as RSA or ECDHE, which allows both sides to securely generate an identical shared secret using asymmetric cryptography.

- Step 4: Session Keys Established

Action: Using the shared secret generated in the previous step, along with the “client random,” and the “server random” values, both parties independently generate identical symmetric session keys. These temporary keys are highly performant and are used to encrypt and decrypt all subsequent bulk data traffic for the remainder of the session. The establishment of these keys marks the official beginning of the secure connection.

Architecting Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS)

Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS) is a modern cryptographic requirement, designed to protect communications from future decryption attempts. PFS ensures that a unique session key is generated for every user, initiated session.

The architectural premise of PFS is highly important: it protects against the scenario where a server’s long, term private key is compromised in the future, rendering historical data that was recorded and encrypted in the past indecipherable. This is achieved by using ephemeral (short, lived) key exchange protocols, primarily Ephemeral Elliptic Curve Diffie, Hellman (ECDHE).

During the TLS handshake, instead of using the server’s static private key, ECDHE allows both the client and server to generate unique, temporary key pairs for that specific session. They exchange the public parts of these keys over the insecure channel and mathematically derive an identical shared secret, which is then used to generate the symmetric session keys. Because these ephemeral keys are never stored and cannot be derived from the server’s static TLS certificate, the compromise of the static certificate does not permit the decryption of any past session data. This is a non, negotiable security requirement, particularly for sectors like financial services and communications.

Performance Metrics: When Speed Meets Security (AES vs. ChaCha20)

Modern cryptography relies on a hybrid encryption model. Asymmetric encryption (like RSA or ECC) is used solely for the initial, computationally expensive task of securely exchanging the session key. Symmetric encryption (like AES or ChaCha20) is then used for the subsequent bulk data transfer. This approach leverages the speed of symmetric ciphers, which can be up to 5,000 times faster for large data sets than asymmetric methods.

A critical consideration in implementation is selecting the appropriate symmetric cipher based on hardware capabilities.

Cryptographic Strength Comparison: Equivalent Key Sizes

To prevent any weak links in the hybrid chain, both the asymmetric key exchange mechanism and the symmetric bulk cipher must offer equivalent security levels. Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) allows for significantly shorter keys while maintaining security strength equivalent to much longer RSA keys, leading to faster handshakes (e.g., ECDHE).

| Security Level (Bits) | Symmetric Key (e.g., AES) | Asymmetric Key (RSA) | Asymmetric Key (ECC) |

| 112 | 3TDEA | 2048 | 224, 255 |

| 128 | AES-128 | 3072 | 256, 383 |

| 192 | AES-192 | 7680 | N/A |

| 256 | AES-256 | 15360 | N/A |

Data synthesized from NIST and IETF guidelines.

AES-256 vs. ChaCha20 in Practice

- AES-256 (Advanced Encryption Standard): This block cipher is the default industry standard for disk encryption and bulk data transfer. When coupled with hardware acceleration, such as Intel’s AES-NI instruction set, AES-256 offers exceptional performance. For fixed computing environments where hardware is consistent and guaranteed (e.g., modern servers or laptops), AES-256 remains the optimal choice. Its 256, bit key makes it practically immune to brute, force attacks.

- ChaCha20 (Stream Cipher): This cipher is optimized for performance in software, only contexts, particularly favored within high, speed protocols like TLS 1.3. ChaCha20’s simpler structure makes it easier to implement correctly, giving it a better safety margin and greater resilience against implementation errors compared to AES. When deploying across highly diverse hardware environments or embedded systems where dedicated AES acceleration may be absent, ChaCha20 (often paired with Poly1305 for authentication) frequently provides a more reliable and predictable performance boost.

The decision between AES and ChaCha20 illustrates a crucial trade, off. While ECDHE adds necessary cryptographic overhead to enable PFS, the subsequent bulk cipher selection determines the channel’s real, world throughput. An organization must choose based on whether it can rely on hardware acceleration (favoring AES) or if it needs robust, efficient software performance across highly varied devices (favoring ChaCha20).

II. The Last Line of Defense: State, of, the, Art Access Control

When network traffic is secured and the application layer is protected, the final defense against compromise often rests on the integrity of the authentication layer, the conversion of a human, chosen password into a cryptographic key.

The Password Hashing Revolution: From PBKDF2 to Argon2id

Traditional password hashing mechanisms struggle against the exponential rise in parallel processing power offered by modern GPUs and ASICs (Application, Specific Integrated Circuits).

The longstanding industry standard, PBKDF2 (Password, Based Key Derivation Function 2), relies almost entirely on increasing the iteration count to slow down brute, force attempts. However, this defense has proven inadequate. Powerful, parallel hardware can still test billions of hashes cheaply. Furthermore, widespread implementation negligence has weakened its standing: many legacy systems default to using outdated algorithms like SHA-1 or critically low iteration counts, making them orders of magnitude weaker than modern standards. Careless implementation, such as silent failure to utilize proper parameters, can also result in the generation of insecure, predictable keys.

The industry mandate has shifted from reliance on computational cost alone to demanding memory hardness. Argon2, the winner of the Password Hashing Competition (PHC), was designed specifically to counter hardware, based attacks. Argon2 demands a significant, non, cacheable amount of RAM to perform its operations. This memory requirement drastically increases the economic cost for attackers who must utilize specialized hardware with limited, expensive memory to launch parallel cracking efforts.

Argon2 comes in three variants, each optimized for different threats: Argon2d (optimized against GPU cracking), Argon2i (optimized against side, channel timing attacks), and Argon2id (the hybrid, recommended variant). Argon2id combines the strengths of both, providing resistance against GPU attacks while minimizing side, channel vulnerability, making it the balanced choice for most modern applications.

Optimizing Argon2id for Maximum Resistance

The theoretical strength of Argon2id is only realized through careful tuning of its three core parameters: the memory cost (m), the time cost (t), and the degree of parallelism (p). The goal is to set these values as high as the authentication server can tolerate without causing unacceptable latency (e.g., keeping hashing time under 500 milliseconds for user login).

This parameter selection is an economic defense strategy. By requiring high memory consumption, Argon2id forces attackers to spend more money on memory, rich hardware rather than relying on standard, cheap GPU farms.

Best Practice Tutorial: Implementing OWASP, Recommended Argon2id Parameters

The parameters must be benchmarked rigorously against the server’s actual resource constraints. Setting the memory cost (m) excessively high risks a denial, of, service (DOS) condition, as the hashing process can exhaust server RAM. The OWASP community provides baseline recommendations that balance security with acceptable latency:

Modern Password Hashing Parameters: Argon2id Optimization

| Memory Cost (m) (MiB) | Time Cost (t) (Iterations) | Parallelism (p) (Threads) | Optimization Trade, off |

| 46 | 1 | 1 | High RAM usage, lower CPU usage |

| 19 (OWASP Minimum) | 2 | 1 | Balanced protection against GPU/ASIC attacks |

| 12 | 3 | 1 | Lower RAM, increased CPU usage |

| 64 (High, End Server Example) | 2 | 4 | Leveraging multi, core parallel processing |

The recommendation of 19 MiB of memory, 2 iterations, and 1 degree of parallelism is considered the baseline for modern application deployment. This choice represents a favorable trade, off between CPU and RAM consumption while ensuring resistance to the dominant threat vectors.

Despite the proven efficacy of Argon2id, poor configuration remains the most common failure point. Data indicates that nearly half of all Argon2 implementations found in public repositories use parameters weaker than the recommended OWASP minimum. Setting the memory cost too low is a fundamental error, as it eliminates the economic barrier the algorithm is designed to create, effectively nullifying its memory, hardness advantage against GPU attacks.

Furthermore, cryptographic strength is never a substitute for password entropy. Research demonstrates that even the strongest Argon2 configurations fail to mitigate risks associated with weak, easily guessed passwords. For dictionary, derived credentials, compromise rates remain above 96% regardless of the hashing algorithm used. This confirms the necessity of pairing Argon2id with strong credential policies, such as enforcing maximum lengths of 64 characters, allowing password managers to operate effectively via copy, paste functions, and mandating Multi, Factor Authentication (MFA) to address the persistent human vulnerability. MFA, utilizing physical security keys or two, factor apps, ensures that a compromise of the hashed password alone does not grant access.

III. Securing Data at Rest: Strategies for Physical Media Protection

Once data leaves the network perimeter and is stored on physical media, a new set of risks emerge, primarily centered around unmanaged USB drives and external storage devices.

The Unmanaged USB Crisis: Risk and Regulatory Fallout

Unencrypted portable media represents one of the most persistent and costly vulnerabilities for organizations.

Financial and Legal Consequences

The financial repercussions of losing sensitive data are severe. The IBM Cost of a Data Breach 2024 report indicates the average global breach cost has climbed to $4.88 million. For financial institutions, this cost rises significantly higher. Regulatory bodies impose steep penalties when data loss involves negligence, such as storing unencrypted information on lost physical media. A notable example involved a UK Local Authority, which incurred an £80,000 fine simply for losing an unencrypted USB stick containing citizen data.

Malware and Policy Evasion

USB drives are not merely passive storage devices, they are sophisticated vectors for corporate network infection.

- Malware Transmission: Malware families like Agent Tesla, AsyncRat, Valyrian, and Gamarue actively spread through USB devices. These drives can execute malicious payloads, software designed to install spyware, leak sensitive data, or corrupt files, the moment they are connected to a business asset.

- Deceptive Files: Attackers exploit file formats to hide malicious code. They use polyglots, files disguised with two different extensions, or embed malicious macros within seemingly innocuous documents, such as Microsoft Office files or PDFs. When a user opens the document and enables macros, the hidden malicious script executes.

- Shadow IT and Compliance: Unmanaged external drives also facilitate “Shadow IT,” allowing employees to bypass licensing agreements by transferring pirated or unauthorized software onto company computers. This exposes the organization to severe compliance fines, potentially reaching $150,000 per violation.

Given the high financial and legal risks, relying solely on user discretion is insufficient. Corporate security must implement a two, pronged defense: mandatory encryption and stringent, centralized administrative control over all removable media access.

Choosing the Right Storage Encryption

When securing data at rest, the choice between hardware, based and software, based encryption impacts performance, security, and portability.

| Feature | Hardware Encryption (e.g., Kanguru Defender) | Software Encryption (e.g., VeraCrypt, BitLocker) |

| Performance | Virtually no performance impact, cryptographic processes handled by dedicated chip. | Can incur severe performance overhead, as encryption uses the main CPU. |

| FIPS/Compliance | Often meets FIPS 140-2 Level 3 standards. | Requires OS/Software certification, generally less compliant for high, security mandates. |

| Portability | Drive is portable, software not required on host PC (just password prompt). | Host PC typically requires OS integration (BitLocker) or software installation (VeraCrypt) to mount the volume. |

The gold standard for storage encryption is AES-256 in XTS mode. AES-256 is mathematically robust, and XTS mode is essential because it eliminates certain pattern, based vulnerabilities that can arise when encrypting large blocks of data (e.g., multi, gigabyte files), ensuring enhanced protection across the entire volume.

VeraCrypt vs. BitLocker To Go:

- BitLocker To Go: Microsoft’s solution, ideal for seamless encryption of USB drives within a Windows environment. However, it typically lacks native cross, platform support and is often restricted to Professional or Enterprise versions of Windows.

- VeraCrypt: A high, security, open, source solution that provides superior cross, platform portability (Windows, Mac, Linux). Although it requires software installation on the host PC to mount the volume, its robust security features make it the preferred choice for cross, platform and high, assurance environments.

Deployment Tutorials for Physical Media Security

Tutorial 1: Implementing VeraCrypt for Portable Security

VeraCrypt allows users to create secure, encrypted file containers that can be stored and transported safely.

- Create Volume:

Action: Launch VeraCrypt and select “Create Volume”. For portability, choose “Create an encrypted file container” to define a secure volume that looks like a normal file but requires the password to mount.

- Encryption Options:

Action: Choose “Standard VeraCrypt volume”. Select the container file path, and in the encryption options screen, choose the robust AES-256 algorithm.

- Password and Size:

Action: Define the size of the virtual volume and choose a strong, unique password. VeraCrypt supports the use of physical keyfiles for added multi, factor protection.

- Format and Completion:

Action: Move the mouse cursor randomly for entropy generation, then click “Format.”

- Accessing the Volume (Mounting):

Action: To use the encrypted data, the VeraCrypt application must be running on the host machine. Click “Select File” (for a container file) or “Select Device” (for an entire drive/partition). Choose an available drive letter from the main window. Click “Mount,” enter the password (and keyfile, if applicable), and click “OK.” The volume now appears as a standard local drive letter.

- Critical Step: Dismounting:

Action: Before physically ejecting the USB drive or external media, the user must select the mounted volume in VeraCrypt and click the “Dismount” button. Gotcha: Failure to dismount properly risks immediate data corruption or loss because file system operations may not have fully completed when the drive is removed.

- Troubleshooting (Header Recovery):

Action: In the rare event of header corruption (preventing the volume from mounting), VeraCrypt includes a recovery function. Users can select the volume, navigate to Tools -> Restore Volume Header, and follow instructions to restore the header from a previously saved backup.

Enterprise Governance Tutorial: Auditing and Blocking USB Access via Windows Group Policy (GPO)

Enterprise security depends on centralized control that overrides user discretion. IT administrators must use Windows Group Policy Objects (GPO) to enforce restrictions.

- Access Group Policy Management Console (GPMC):

Action: Open the GPMC, create a new GPO, and link it to the relevant Organizational Unit (OU) containing the corporate endpoints.

- Navigate to Storage Restrictions:

Action: Browse to

Computer Configuration > Policies > Administrative Templates > System > Removable Storage Access. - Implement Blocking Policies:

Action: To prevent unauthorized data exfiltration and malware introduction, enable the following two policies:

Removable Disks: Deny write access: This prevents employees from copying any data from the corporate machine onto unauthorized external media.Removable Disks: Deny execute access: This prohibits malicious programs stored on the USB drive from running automatically when connected.

- Mandatory Auditing (Event Viewer):

Action: To satisfy audit requirements and track unauthorized activity, administrators must ensure Windows is logging USB events.

- Action: Navigate to

Application and Services Logs > Microsoft > Windows > DriverFrameworks-UserMode. - Action: Right, click the

OperationalLog, select Properties, and ensureEnable Loggingis checked.

This action forces the system to maintain a detailed audit trail of USB connection events, allowing administrators to track device access times and authorization attempts post, incident.

- Action: Navigate to

IV. The Digital Rights Frontier: DRM, Piracy, and Circumvention

Digital Rights Management (DRM) is technology designed to enforce copyright restrictions on digital media, limiting how legitimate consumers can use purchased or licensed content. This area illustrates a conflict where complex technological security measures frequently hinder the user experience without fully deterring determined piracy.

The Unsolvable Problem: The Analog Hole Principle

The primary limitation of all DRM schemes is an inescapable paradox: the Analog Hole. If digital content must be converted into a human, perceptible analog form (e.g., pixels on a screen, sound waves from speakers) for consumption, that analog output can be digitally recaptured in an unrestricted format. This fundamental weakness means that no matter how sophisticated the encryption or licensing controls are, once the content is visible or audible, it has bypassed all digital restrictions.

The existence of the Analog Hole explains why sophisticated leaks often originate from authorized users, accounting for nearly one in three video leaks. Since stopping the leak entirely is impossible, publishers rely on forensic watermarking. This technique embeds unique, dynamic, and often invisible identifiers into the content on a per, session or per, user basis. If a leak occurs, this watermark allows the publisher to definitively trace the unauthorized copy back to the specific individual or device responsible.

DRM in Action: Widevine Security Levels and HDCP

Digital streaming platforms employ multi, DRM systems like Widevine (Google), PlayReady (Microsoft), and FairPlay (Apple). These systems dictate content quality and access based on the integrity of the device’s decryption environment. Widevine, which governs Android and Chrome, based streaming, illustrates this enforcement hierarchy:

- Widevine L3 (Software Decryption): This is the minimum security level. Decryption occurs entirely in the device’s software environment (the OS). Since the unencrypted video stream is visible to the operating system’s window compositor, screen recording is technically feasible, though streaming quality is typically restricted to Standard Definition (SD) or low High Definition (e.g., 720p maximum) to discourage capture.

- Widevine L1 (Hardware Decryption): Required for high, quality streams (1080p and 4K content). L1 mandates a full chain of trust, meaning the encrypted stream is routed directly to a dedicated, secured cryptographic chip (GPU or system, on, chip). The hardware actively prevents the OS from accessing the decrypted video buffer. L1 also requires a successful HDCP (High, Bandwidth Digital Content Protection) handshake with the connected display device to ensure the display itself is trusted.

To further mitigate the analog hole and deter capture, streaming services often employ high, frequency key rotation. The decryption key is changed every few seconds (e.g., every 10 seconds). This renders any key stolen during a capture attempt obsolete almost immediately, ensuring that only a small segment of the stream can be decrypted before the key expires.

The consequence of aggressive DRM and HDCP enforcement is often a direct penalty to the legitimate user experience. While determined pirates easily bypass HDCP L2/2.2 using inexpensive hardware splitters, legitimate users are often met with black screens or connection errors when using older monitors, specific adapters, or screen, sharing tools. This paradoxical outcome demonstrates that DRM’s technical friction disproportionately affects authenticated consumers.

Piracy Mitigation and Troubleshooting Tutorials

When a screen capture utility or a browser environment clashes with DRM enforcement, a “black screen” is the common result, often accompanied only by audio playback.

Tutorial 1: Screen Capture Bypass , Disabling Hardware Acceleration

The black screen occurs because the browser and GPU route the video through a protected pipeline (L1/HDCP) that is hidden from the operating system’s screen recording APIs. One temporary workaround is to disable the secure pipeline by forcing the decoding process onto the main CPU.

- Identify the Root Cause:

Action: A black screen indicates that the browser is enforcing content protection policies, usually Widevine L1 or HDCP.

- The Workaround:

Action: Disable the hardware acceleration feature in the browser settings. This forces the GPU to surrender control, breaking the dedicated secure video path.

- Step-by-Step (Google Chrome):

Action: Click the three, dot menu, navigate to “Settings,” and then click System.

- Action: Locate the toggle labeled “Use hardware acceleration when available.” Toggle this setting OFF.

- Action: Confirm the prompt to relaunch the browser for the new setting to fully take effect.

- Test the Protected Video:

Action: Start the protected stream and activate the desired screen capture tool.

Verification: The recording should now display the video content clearly, replacing the previous black screen.

Gotcha: If the video still renders a black screen after disabling hardware acceleration, the content provider is strictly enforcing L1. At this stage, a technical attacker must resort to a hardware, level bypass, such as an HDCP stripper.

Tutorial 2: PDF Restriction Removal , Unlocking Copying and Printing

PDF files frequently employ password security, typically relying on an “owner password” (or permissions password) to restrict actions like copying, editing, or printing. If the user knows the password required to open and view the document, these permissions can often be cleared by re, saving the file through a modern browser’s internal PDF renderer.

Steps (Using Chrome or Edge Browser):

- Open the Restricted PDF:

Action: Drag and drop the restricted PDF file directly into the browser window.

- Initiate Printing:

Action: Press

Ctrl+P(Windows) orCmd+P(Mac) to open the standard print dialogue box. - Select Destination:

Action: Change the printer destination dropdown list from a physical printer to “Save as PDF”.

- Save the New File:

Action: Click “Save” and choose a destination and name for the newly processed file.

Verification: Open the newly saved file in any PDF viewer. It will now allow unrestricted copying of text blocks and printing of the document, proving the original restriction was merely a policy directive.

Alternative Removal (With Known Password): If the permissions password is known, the creator or authorized user can remove restrictions using Adobe Acrobat. The user navigates to “Tools” > “Protect” > “Encrypt” > “Remove Security,” inputs the password, and confirms the removal.

V. Software and App DRM: The Offline Barrier

Protecting installed applications and games often involves verifying license authenticity, which historically led to the controversial practice of Always, On DRM (AODRM).

A. The Failure of Always, On DRM (AODRM)

AODRM requires the customer to maintain a constant internet connection to an authentication server to use a purchased product, even for single, player modes. This policy was designed to prevent piracy by making core application functions reliant on continuous server checks.

AODRM proved to be highly user, hostile. Forcing constant connectivity introduced a single point of failure. When authentication servers went down, legitimate paying customers were locked out of games like Diablo III and SimCity. The resulting user backlash was severe. Furthermore, AODRM rarely stopped determined pirates, who focused their efforts on cracking and patching the authentication routines to isolate the core application from the online check.

B. Comparison: Major Multi, DRM Systems

A more sophisticated approach involves managing the lifespan of the content key through key rotation, rather than requiring constant user connectivity. Key rotation periodically changes the encryption keys during live playback, such as during a streaming event. High, frequency key rotation, where the key is switched every few seconds (e.g., every 10 seconds), makes traditional file capture and ripping techniques extremely difficult because the captured data segments are encrypted with an already expired key.

Content strategists must choose a multi, DRM solution because enforcement relies on integrating platform, specific systems across diverse operating environments.

Comparison of Leading DRM Ecosystems

| Criterion | Google Widevine | Microsoft PlayReady | Apple FairPlay |

| Primary Ecosystem | Android, Chrome, Smart TVs | Windows, Edge, Xbox | iOS, macOS, Safari |

| Complexity for Provider | Lower (Licenses easily provided) | Moderate (Requires Content Certificate) | Higher (Requires Content Certificate) |

| Hardware Dependence | L1 is mandatory for UHD/HD | Strong integration with Windows | Required for high assurance |

| Best Use Case | Broadest cross, platform reach | Enterprise Windows environments | Exclusive Apple device distribution |

While the underlying cryptography used across these platforms is similar, the complexity for the content provider differs significantly. Apple and Microsoft require content owners to obtain specific, proprietary certificates to issue licenses, creating an administrative bottleneck. Google’s Widevine often integrates more flexibly with third, party DRM licensing services, simplifying cross, platform implementation.

VI. Forensic Tracing: The Strategy After the Leak

Acknowledging that the Analog Hole ensures content can be stolen, the most realistic defense shifts from absolute prevention to ensuring that every leak is traceable. This is achieved through forensic tracing, which makes content theft an immediate accountability failure.

The distinction between simple watermarking and dynamic fingerprinting is critical here. Static watermarking involves a fixed, visible logo or overlay. This is easily defeated by cropping the frame, blurring the mark, or using accessible AI tools designed to erase predictable overlays. This method is quickly becoming obsolete.

Dynamic Fingerprinting is the required solution. This process embeds a unique, variable mark specific to the authenticated user, session, or device. The mark might display the user ID, session timestamp, or a unique cryptographic token, often changing location or visibility randomly throughout the playback. A forensic system can then analyze a leaked copy and instantly trace it back to the authorized user responsible for the breach.

Forensic tracing is paramount because the internal threat is severe. Authorized users, including employees, partners, or paying customers, are responsible for nearly one-third of all video leaks. A strong dynamic watermarking system turns the content itself into an indispensable accountability and audit mechanism.

4.2. Session, Based Forensic Watermarking

Forensic watermarking is the technical solution used to address the analog hole. It involves dynamically overlaying unique, session, specific identifiers onto the visual content during playback. This mark is tied directly to the authorized user’s account, session ID, and timestamp. The watermarks can be visible (a clear deterrent) or embedded subtly into the pixel data, ensuring the mark survives external camera capture, compression, cropping, and re, encoding.

When combining traditional DRM with session, based forensic watermarking, content owners ensure that if a copy leaks, the media pirate can be positively identified and potentially held criminally liable.

Share, Safely Example (Deterrent Implementation)

Action: A content publisher releases a high, value video course protected by Widevine L1. Before streaming, the publisher applies mandatory forensic watermarking that subtly but permanently displays the user’s account ID and the current IP address throughout the video stream. If this video appears on an unauthorized platform, the publisher instantly extracts the embedded user ID from the leaked file. This proof of work provides the evidence required for immediate license revocation and supports legal proceedings against the authorized user who betrayed the terms of service.

VII. Troubleshooting DRM Playback Failures

Most instances of DRM playback failure are not due to a content hack or a breakdown in the encryption itself. Instead, they are usually the result of user, side configuration errors, such as VPN usage, disabled browser modules, or unsupported display resolutions. Addressing these issues reduces user friction and minimizes support load.

The ranked root causes include a missing or corrupted Widevine module, VPN usage triggering geo, blocking, non, compliant display resolutions (below 720p), and device conflicts such as active macOS AirPlay functionality.

B. Troubleshoot Skeleton: Symptom $\to$ Verified Fix

This table provides specific resolutions for common DRM error symptoms, focusing on non, destructive user fixes.

Common DRM Playback Errors and Solutions

| Symptom | Root Cause | Non, Destructive Test / Fix for User | Mitigation for Publisher |

| Video plays audio but screen is black (Mac/PC) | Widevine L3 attempt failed, OS capture blocking video stream. | Action: In Chrome/Brave settings, navigate to system settings and re, enable “Use hardware acceleration when available,” then relaunch the browser. | Enforce minimum L1 requirement for HD content, or dynamically restrict quality to SD if L1/HDCP fails compliance checks. |

DRM Error Code (PLAYER_ERR_DASH_DRM_KEY_SESSION) |

Missing, disabled, or corrupt Widevine Content Decryption Module. | Action: Navigate to chrome://settings/content/protectedContent and ensure “Sites can play protected content” is selected. |

Provide clear, platform, specific support documentation guiding users to enable protected content settings for their browser. |

| Geo-blocking Message or “Content not available” | VPN or proxy is active, masking true user location. | Action: Disable VPN/proxy. Verify geographical region availability. | Monitor and respond to VPN/proxy usage by restricting access or requiring identity verification. |

| Playback Refuses to Start (low quality) | Device resolution below the 720p or 1080p DRM minimum requirement. | Action: Adjust device display settings to 720p or higher. | Enforce minimum resolution requirement based on security policy. |

| Playback Fails on macOS | AirPlay mirror casting may violate HDCP restrictions. | Action: Turn off AirPlay functionality on the macOS device. | Provide clear user guidance on disabling mirroring features. |

5.3. Hardening Defenses Against Common Hacks

Publishers must implement strict policies to counteract known technical exploits.

Mitigating the Hardware Acceleration Trick: When users disable hardware acceleration, they deliberately force the playback system into the vulnerable Widevine L3 software mode. The only reliable defensive solution is to adopt an uncompromising policy: L1 or HDCP failure must trigger an immediate, dramatic restriction of content quality or a complete halt to playback. Content quality should be proportional to the reported security level.

The VDI Threat (Citadel Strategy): Protecting highly confidential or internal training materials demands securing the endpoint environment itself. Adversaries often use virtual machines or compromised remote access sessions to capture screens. The enterprise solution is robust sandboxing. Tools like Citrix Workspace App Protection are necessary to defeat screen capture within the session by scrambling keystrokes (anti, keylogging) and blocking the OS’s screenshot APIs, ensuring that protected content remains inaccessible even within a VDI environment.

Section 6: Future, Proofing and Final Strategy

The longevity of a content protection system depends on its ability to evolve and its acceptance by the paying user base.

6.1. Balancing Security and User Experience (UX)

An effective DRM strategy must balance maximal protection with a smooth user experience, avoiding frustrating technical hurdles, constant logins, or unexpected playback failures. The strategic goal is that security mechanisms, especially for video, should operate invisibly. However, document protection that requires proprietary viewers, while highly secure, introduces unavoidable installation friction. Publishers must carefully assess their audience’s willingness to adopt new software. While a solution like Locklizard offers maximum security by enforcing its proprietary client and OS hooks, a mass, market publisher might prioritize wider accessibility over absolute security, accepting the risk posed by browser or plugin, based DRM. The choice should always reflect the highest level of security that the target customer base will accept without actively seeking circumvention methods.

6.2. Final Verdict by Persona

The optimal anti, capture solution varies based on the type of asset, the financial value, and the audience distribution mechanism.

Final Content Protection Strategy Verdict

| Persona | Primary IP Asset | Recommended Anti, Capture Strategy | Key Trade, off |

| Online Course Creator (SMB Admin) | 1080p Video Tutorials | Widevine L1 enforcement + Session, Based Forensic Watermarking. | Watermarking is slightly visible (a minor UX cost), but it guarantees traceability if a device falls back to weaker L3 protection. |

| Financial/Legal Publisher | PDF Research Reports, Compliance Manuals | Proprietary Secure Viewer (e.g., Locklizard or VeryPDF). | Highest security against document leakage, but requires users to install new viewing software, adding significant customer friction. |

| Enterprise Training Manager | Internal SaaS Apps, Confidential Demos | VDI solution (e.g., Citrix App Protection) and multi, DRM enforcement for streamed media. | High initial cost and complexity for VDI implementation, but essential for preventing insider leaks and protecting highly sensitive internal data. |

Section 8: Protecting Portable Assets: The USB Encryption Imperative

Physical media, particularly USB drives, remains one of the most significant attack vectors and sources of data loss for organizations. Malware families such as Agent Tesla, AsyncRat, and Gamarue actively attempt to spread through USB storage devices moved between personal and corporate systems.

More critically, unencrypted physical media represents a massive compliance risk. The average global cost of a data breach reached $4.88 million in 2024, rising to $6.08 million for financial industry enterprises. Failure to encrypt removable storage leads to significant regulatory penalties. For example, one UK local authority faced an £80,000 fine after losing an unencrypted USB stick containing confidential data.

Encryption of removable storage is not optional, it is fundamental compliance. Corporate environments must enforce policies using Group Policy Objects (GPO) in Windows to deny execute, read, or write access to unauthorized removable storage devices. Active security monitoring tools like SafeConsole allow administrators to remotely manage and audit encrypted drives. Administrators can also audit local device usage by checking the Windows Event Viewer’s DriverFrameworks-UserMode > Operational log.

B. Comparison: BitLocker vs. VeraCrypt

Choosing the right encryption solution depends heavily on the organizational need for cross, platform portability versus ease of deployment within a Windows environment.

Comparison of USB Encryption Tools

| Criterion | Windows BitLocker To Go | VeraCrypt (Open Source) |

| Portability / OS Support | Windows-centric (requires manual setup on Mac/Linux) | Fully Cross, Platform (Windows, macOS, Linux) |

| Availability | Requires Windows Pro/Enterprise/Education | Free to use on all platforms |

| Security/Robustness | Strong, but proprietary. Does not encrypt external drives by default. | More robust and auditable (open, source) |

| Key Management | Requires Microsoft Recovery Key | Volume Header backup/restore possible |

BitLocker is easier for Windows users due to its native integration. However, its dependency on specific Windows editions and its proprietary nature make it unsuitable for environments requiring cross, platform data exchange. VeraCrypt, which is free and open, source, provides superior flexibility and security auditing features necessary for true enterprise, level protection, despite its steeper learning curve.

If an encrypted drive is lost, the data remains inaccessible to recovery tools unless the correct password or decryption key is provided first. The vulnerability shifts entirely to the user’s key management practices.

IX. Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Does disabling hardware acceleration weaken my general security?

A: Disabling hardware acceleration bypasses software, level DRM for video playback, but it does not generally weaken core security layers like HTTPS. It may increase the Central Processing Unit (CPU) load, which can degrade performance for other tasks.

Q2: How long does it take to break AES-256 encryption?

A: AES-256 is mathematically robust and effectively uncrackable using current brute, force methods. It would take modern supercomputers trillions of years to guess the key, confirming that the vulnerability lies in key management, not the algorithm itself.

Q3: Is the padlock icon (HTTPS) the same as End-to-End Encryption (E2EE)?

A: No. The HTTPS padlock confirms Transport Layer Security (TLS), which encrypts data only between your device and the server. E2EE (e.g., Signal Protocol) ensures only the two communicating endpoints hold the keys, meaning the intermediary server cannot decrypt the content.

Q4: Can a hacker still bypass DRM if I use high-frequency key rotation?

A: High, frequency key rotation makes traditional file, capture attacks (ripping) extremely difficult because the decryption key expires rapidly, often every 10 seconds. However, it does not defeat the Analog Hole, a user can still re, record the screen output using an external camera or physical HDCP bypass hardware.

Q5: What are the risks of using unmanaged USB drives at work?

A: Risks include malware infection (e.g., Agent Tesla, AsyncRat), significant financial penalties due to data loss (e.g., £80k fine), and risks associated with piracy or unauthorized software transfer.

Q6: Why is ChaCha20 sometimes preferred over AES-256?

A: ChaCha20 is a stream cipher that performs exceptionally well in software, only contexts and general CPUs, making it ideal for low, latency network protocols like TLS 1.3. AES-256 is typically preferred for disk encryption where hardware acceleration (AES-NI) is available.

Q7: How do organizations audit USB drive usage on corporate networks?

A: Organizations can use Group Policy Objects (GPO) to restrict or deny unauthorized removable storage access. For active logging, administrators can check Windows Event Viewer’s DriverFrameworks-UserMode > Operational log or deploy central management tools like SafeConsole.

Q8: If I lose an encrypted USB drive, can the data be recovered?

A: Data recovery tools cannot access files stored on an encrypted drive unless the correct password or decryption key is provided first. Recovery efforts must first focus on successfully unlocking the volume using the correct credentials.

Q9: Why did Always, On DRM fail with games like SimCity and Diablo III?

A: AODRM created a Single Point of Failure. When authentication servers suffered downtime or outages, legitimate paying customers were locked out of the product entirely, leading to massive user frustration and abandonment.

Q10: What is the benefit of dynamic watermarking over a static logo?

A: A static logo is easily removed, cropped, or blurred. Dynamic watermarking uniquely identifies the specific user session by embedding variable account details into the content stream, making the content a forensically traceable accountability tool.

X. Final Thoughts: Realistic Defense and Deterrence

Content copy protection demands a layered security model built on realistic expectations. Reliance on a single layer of software DRM is a failing strategy because the Analog Hole is an insurmountable limitation.

True digital protection requires combining robust, hardware, enforced DRM (L1) to handle the casual, external threat, with the indispensable layer of forensic dynamic watermarking to deter and track the trusted, internal leaker.

The cost of inaction is too high to ignore. Compliance failures and data loss are financially catastrophic, the average cost of a breach in the financial sector hit $6.08 million in 2024. Therefore, the deployment of basic full, disk encryption solutions, such as BitLocker or VeraCrypt, is not merely a best practice, it is a fundamental compliance mandate.

For maximum assurance when high, value assets must travel outside the secured network, organizations should mandate hardware, encrypted USB drives. These devices (such as FIPS 140, 2 certified units) ensure that all cryptographic processes are isolated and tamper, resistant, maintaining data integrity even if the physical drive is lost.