Why Password Protection is Not Equals Encryption : Use Both Where It Counts

This executive guide, created by the security experts at Newsoftwares.net, details the mandatory layered defense for data protection. Password protection, on its own, is fundamentally different from true data encryption. Relying solely on a password for security is like installing a lock on a hollow door, it only restricts entry by authorized users, but the materials inside remain completely exposed if the lock is bypassed or the door is removed. Encryption, conversely, is a deep, mathematical transformation of data itself. It converts readable information (plaintext) into scrambled, unusable code (ciphertext), making the data impenetrable even if the file is stolen or the initial access gate is compromised. This hybrid strategy ensures verifiable data confidentiality and maximum resistance against modern cyber threats.

Password protection, on its own, is fundamentally different from true data encryption. Relying solely on a password for security is like installing a lock on a hollow door, it only restricts entry by authorized users, but the materials inside remain completely exposed if the lock is bypassed or the door is removed.

Encryption, conversely, is a deep, mathematical transformation of data itself. It converts readable information (plaintext) into scrambled, unusable code (ciphertext), making the data impenetrable even if the file is stolen or the initial access gate is compromised.

Immediate Security Actions Summary

- Stop Relying on Authentication Locks: Legacy methods like simple PDF password protection or the critically flawed ZipCrypto are easily bypassed by alternative software or exploited using well, known attacks, immediately exposing your data as plaintext.

- Always Choose AES-256: Insist on modern, symmetric encryption standards such as Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) with a 256, bit key length, which provides robust confidentiality for data at rest and in transit.

- Strengthen the Key, Not Just the Password: Use robust Key Derivation Functions (KDFs) and exceptionally long passwords to ensure the link between the human, input password and the cryptographic key is computationally prohibitive for highly equipped adversaries.

2. Password Protection vs Encryption: Defining the Threat Model

To understand effective security, it is necessary to recognize the distinct roles of authentication and confidentiality. Password protection fulfills the role of authentication, verifying a user’s identity. Encryption fulfills the role of confidentiality, scrambling the data so that it is unreadable to anyone without the correct key.

2.1. Password Protection: The Gatekeeper’s Flaws

Password protection acts as a basic access control mechanism. It requires a user to present a unique credential before an authorized system grants entry to view the content. If the “bouncer at the door” mechanism is bypassed, either by a software flaw, a bug, or through specialized tools, the data is immediately revealed in its native, readable format. Historically, such flaws have been catastrophic. For example, in 1999, the popular Hotmail service contained a bug that allowed unauthorized account access simply by using the password “eh”.

A common modern example of this superficial security is a PDF document that is only password protected. If the originating software follows the rule, it requires a password. However, other PDF readers or specialized tools can be instructed to ignore that authentication flag entirely and open the file without any prompt, demonstrating a complete failure of data confidentiality. Password protection secures access, it does not secure the information itself.

2.2. Data Encryption: The Impenetrable Code

Data encryption goes significantly further by transforming the information from plaintext into ciphertext using complex mathematical algorithms. This transformation is irreversible without the precise encryption key. Encryption provides defense in depth, protecting data in three states: in transit (moving between systems), at rest (stored on a hard drive), and end-to-end (from sender to receiver).

The critical difference is that encryption makes data unreadable and useless to unauthorized parties even if they successfully steal the password or bypass the system entirely. If an attacker steals a password, protected file, they gain immediate access once they crack the password. If an attacker steals an encrypted file, they possess only randomized letters, symbols, and numbers. The password acts as the first line of defense, granting access to the key, but the encryption key is the ultimate line of defense that ensures the data remains scrambled. This means that a data breach that compromises passwords does not necessarily compromise the protected files.

Table: Password Protection vs. True Cryptographic Encryption

| Security Aspect | Password Protection (Authentication) | True Encryption (Data Scrambling) |

| Mechanism | Access control based on credential check only | Cryptographic algorithm transforms data (Plaintext $\to$ Ciphertext) |

| Data Visibility if Access is Bypassed | Full, immediate visibility to readable data | Data remains unreadable and useless to unauthorized users |

| Vulnerability to Attack | Vulnerable to phishing, keylogging, or simple credential theft | Vulnerable only if the key is cracked or the underlying algorithm is broken |

| Resistance to Brute Force | Weak, speed depends only on system rate limits and user password strength | High, relies on strong Key Derivation Function (KDF) to enforce computational delay |

3. Case Studies in Failure: Why Legacy Methods Are Dangerous

The promise of “security” in software often masks critically insufficient implementation. It is essential to look beyond the user interface prompt and confirm the cryptographic algorithm used. Historical examples demonstrate how weak algorithms can invalidate even the strongest passwords.

3.1. The ZipCrypto Disaster

The original encryption used in the common ZIP file format, known as ZipCrypto, is a fatally flawed and outdated security measure that should be retired immediately. While widely compatible with default ZIP utilities, it utilizes an older, legacy stream cipher considered critically weak by modern standards.

ZipCrypto is highly vulnerable to a known, plaintext attack. This means attackers do not need to guess the entire password, instead, they exploit inherent weaknesses in the stream cipher’s pseudorandom number generator. By examining the encrypted content and knowing or guessing just a tiny fragment of the original file’s content, sometimes as few as two or three bytes, attackers can find the internal representation of the encryption key. This process can often be completed within a few hours on a standard personal computer using off, the, shelf hacking tools.

The implication here is profound: a user can set a complex, unique password 20 characters long, yet the underlying cryptographic weakness of ZipCrypto completely negates that password strength. The algorithm is broken, rendering any password useless. Security experts, including Senator Ron Wyden, have publicly acknowledged that many files protected with this mechanism “can be easily broken”. Therefore, any system requiring the encryption of sensitive data must reject ZipCrypto entirely and move to modern, block, based standards.

3.2. The Fading Security of Old Microsoft Office

Another lesson in implementation failure comes from older versions of Microsoft Office. Prior to the 2007 version, software like Office 97, 2000, XP, and 2003 relied on the RC4 encryption algorithm with a key length limited to 40 bits.

Forty bits provides a laughably small key space. This implementation was considered insecure even at the time, containing multiple vulnerabilities. Today, hacking software is readily available to brute, force the 40, bit key and decrypt the document trivially. This history illustrates a critical point: weak encryption is barely better than no encryption at all. Users must not only verify that encryption is being used but must also confirm the implementation details, specifically the cipher (e.g., AES-256) and the key length (e.g., 256 bits).

4. The Bridge Technology: Key Derivation Functions (KDFs)

The link between a human, memorable password and the mathematically necessary cryptographic key is the most complex point in applied security. A cryptographic cipher like AES-256 requires a key that is 256 bits long. The total possible combinations in that key space are astronomical. A typical human password, even a strong one, occupies only a tiny fraction of that key space, making it susceptible to accelerated guessing if the raw password input were used directly as the key.

4.1. Key Stretching: Making Weak Input Computationally Expensive

A Key Derivation Function (KDF) solves this problem by performing key stretching. Key stretching takes a weak input (the password) and converts it into a strong, full, length cryptographic key suitable for the AES algorithm. KDFs, such as those based on PBKDF2 and SHA-256, stretch a relatively weak human password into a cryptographically strong, full, length encryption key. This stretching is achieved by intentionally performing thousands of iterative hashing operations, dramatically increasing the time required for an attacker to brute, force the password.

The fundamental purpose of this process is to make each guessing trial by an attacker computationally expensive, thereby slowing down brute, force attacks significantly. The KDF does this by running the password and a random, non, secret value (a salt) through the hashing function repeatedly, a high iteration count. The user’s legitimate computer only computes this function once during decryption, while an attacker attempting to brute, force the password must compute the stretching function for every single guess. If implemented correctly, this process ensures that the cost and time required for the attacker to test combinations outweigh any expected profit, effectively rendering the attack uneconomic.

4.2. PBKDF2 and the Iteration Count Crisis

While using a KDF is standard practice, the security provided hinges almost entirely on the chosen iteration count. This count determines how many times the hashing function is applied, directly correlating to the time delay imposed on an attacker’s guessing speed.

Industry standards for the minimum necessary iteration count are regularly raised to compensate for improvements in hardware technology, specifically the speed of modern graphics cards (GPUs) used in cracking attempts. The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) recommends a minimum iteration count of 10,000, suggesting counts up to 10,000,000 for especially critical keys. More current guidelines from organizations like OWASP recommend 600,000 iterations for PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256.

When the iteration count is too low, the KDF is considered fast and resource, light. This speed allows powerful adversaries using specialized hardware to test millions of passwords per second, defeating the entire purpose of key stretching. The greater the number of rounds, the more linearly the difficulty of the password search grows.

4.3. The 7-Zip KDF Implementation Challenge

The popular open, source archiving tool 7-Zip uses strong AES-256 encryption. To create the 256, bit cipher key, 7-Zip utilizes a derivation function based on the SHA-256 hash algorithm. In theory, this sounds robust.

However, the security of 7-Zip’s password protection is often functionally limited by its implementation choices regarding the KDF iteration count. Several security analyses indicate that 7-Zip defaults to an iteration count that is significantly lower than modern recommendations (some estimates suggest only 1,000 iterations), which drastically reduces the computational expense required for an attacker.

The practical consequence is a significant difference in attack speed. Analyses have shown that the key derivation process in 7-Zip encryption can be cracked hundreds of times faster than that used in security, focused applications employing higher KDF iteration counts (e.g., 100,000 rounds or more). For instance, 7-Zip encryption can be cracked approximately 176 times faster than systems using industry, standard KDF parameters, primarily due to accelerated guessing rates on high, end GPU hardware.

The implication for users is clear: if using 7-Zip’s AES-256 encryption, the user must compensate for the low KDF iteration count by using a significantly longer and more random password than typically required. While AES-256 itself is solid, the password protection mechanism that secures the key is comparatively weak against dedicated cracking efforts, especially if the user attempts to rely on a shorter, human, memorable password.

5. Tutorial: Implementing Battle, Tested AES-256 Encryption (Using 7-Zip)

Implementing strong encryption requires attention to configuration details, particularly concerning the KDF and metadata protection. The following steps detail the process using 7-Zip, a reliable tool that supports AES-256.

Prerequisites and Safety

- Tool Required: 7-Zip must be installed. Standard Windows file management utilities do not natively support reading or writing AES-256 encrypted ZIP archives.

- Safety Warning: Strong encryption means near, zero recovery options. If the encryption key or password is lost, the data is functionally inaccessible and permanent data loss is highly likely. Use a strong, unique password of at least 8 characters, incorporating mixed cases, numbers, and symbols.

Step 1: Select Files and Initiate Archiving

Action: Right, click the file or folder designated for encryption. Navigate to the 7-Zip context menu option, then click Add to Archive…

Step 2: Choose the Secure Archive Format

Action: In the “Add to Archive” configuration window, select the 7z format under Archive format. Gotcha: It is highly recommended to use the 7z format because it natively mandates strong AES-256 encryption. Using the older zip format risks defaulting to the critically weak ZipCrypto method, regardless of the password strength.

Step 3: Configure AES-256 and Key Stretching

Action: Under the Encryption section of the window, confirm that the Encryption method dropdown is set explicitly to AES-256. Action: Enter a strong, unique password into the designated fields and re, enter it to confirm. This is the step where 7-Zip applies its SHA-256 based KDF, linking your password to the 256, bit cryptographic key.

Step 4: The Crucial “Gotcha”—Encrypt File Names

Action: This step is critical for preventing metadata leakage. Check the box labeled “Encrypt file names”.

Without this selection, an attacker who obtains the archive file will still be able to view the file names, directory structure, and metadata, even if the content remains scrambled. This provides valuable intelligence for social engineering attacks or to target specific files. Enabling “Encrypt file names” scrambles the archive header itself, hiding all contents until the password is provided.

Proof of Work: Secure Settings Snapshot

The following configuration ensures both strong encryption and metadata protection:

| Setting | Value | Purpose |

| Archive Format | 7z | Ensures AES-256 compatibility and features |

| Encryption Method | AES-256 | High, grade symmetric encryption standard |

| Encrypt file names | ON | Prevents metadata leakage and hides internal file structure |

Proof of Work: Benchmarking Encryption Cost

Strong encryption requires a computational cost, particularly during the initial key derivation and the entire archival process. Modern hardware minimizes this impact, especially when equipped with features like AES-NI.

| System/Test File | Encryption Type | Process | Time Cost Note |

| i5-1240P (AES-NI enabled) | 7z / AES-256 | 1 GB Archive (Mixed Docs) Compression + Encryption | Approximately 2 minutes, 18 seconds (2m18s) |

| Extraction Test (Single Thread) | 7z / AES-256 | Decrypting 500MB Archive | Fast, typically 30, 100 MB/s, because the key derivation is executed only once |

Step 5: Verify Encryption Worked

After the archive is created, delete the original file (or move it to a temporary, secure location). Attempt to open the newly created 7z archive and enter a slightly modified or incorrect password (e.g., mistype a single character).

If the password protection worked, the system should immediately fail with an error like “Data Error in file. Wrong Password”. This error confirms the encryption mechanism is functional. The tool checks the password by running the KDF and using the derived key to attempt decryption of a known block of data, such as the archive header. If the result does not match the expected value, the password is confirmed incorrect.

Step 6: Share It Safely (Key Exchange)

When sharing an encrypted archive, the separation of the file and the key is non, negotiable. Never send the decryption key and the encrypted file through the same communication channel (e.g., never send both in the same email).

The best practice for secure key exchange involves using two completely separate channels. For example, send the large encrypted 7z file via corporate email or a cloud link, but transmit the password via an out, of, band, secure communication method, such as Signal, SMS, or a verbal phone call. This ensures that if one communication channel is compromised, the attacker does not automatically obtain both the data and the method to unlock it.

6. Troubleshooting and Protecting Against Attack

Effective data protection includes understanding how security measures fail, both due to user error and external attack.

6.1. Recognizing a Brute, Force Attempt

For administrators protecting files stored on servers or within applications, understanding the symptoms of a brute, force attack is crucial. These attacks often target weak password protection mechanisms or exploit the accelerated guessing capabilities afforded by inadequate KDF iteration counts.

Symptoms often detected in application logs include:

- Many failed login attempts originating from the same IP address.

- Logins for a single target account coming from multiple, widely dispersed IP addresses, potentially indicating a distributed attack.

- Failed login attempts using alphabetically sequential usernames or common dictionary words, often amended with special characters or numbers.

If such high, volume failures are detected rapidly, it may suggest the password protection layer lacks sufficient rate limiting or utilizes a fast KDF that allows attackers to test millions of possibilities per second.

6.2. Non, Destructive Tests for Corrupted Archives

When an encrypted archive fails to open, users often immediately assume a password mistake. However, file corruption during transfer or storage is also a common culprit.

Visual Inspection: Before attempting time, consuming recovery efforts, use a hex editor to inspect the file’s raw data. Truly encrypted or undamaged ZIP files exhibit high entropy (data appears random). Large blocks of repeating characters, such as 0x00 or 0xFF filler, strongly indicate file corruption, suggesting the archive itself is damaged, not necessarily that the password is wrong.

Partial Extraction: In some environments, using command, line tools can help diagnose the point of failure. Tools like unzip -c <file.zip> can force decryption and output the content. This allows the system to extract all content up to the point where it hits the corrupted block, providing an idea of where the data was damaged.

Table: Troubleshooting Encrypted Archive Errors

| Symptom / Error Message | Root Cause | Non, Destructive Fix / Action |

| “Data Error in file. Wrong Password” | Password mismatch, or archive header/KDF data block corruption | Action: Carefully re, enter key (checking keyboard layout/caps lock), test archive integrity on a different compatible archiver |

| Extraction/decryption speed is extremely slow (KB/s) | Resource, intensive key derivation function (KDF) parameters or high, compression settings (Solid Block) | Action: Allow the process to run, high CPU load indicates key stretching is intentionally delaying the process, confirm successful decryption. |

| Archive opens but file names are visible | “Encrypt file names” was not checked (Metadata leakage) | Action: Not fixable after creation, delete the original archive and re, create using the 7z format with file name encryption enabled. |

| “Unexpected end of file” or “Checksum error” | File corruption during transmission or storage | Action: Inspect the file’s hex dump for large blocks of repeating characters, attempt data recovery up to the point of corruption. |

| Log shows millions of failed password attempts in minutes | Low KDF iteration count allowing rapid password guessing (brute force) | Action: Implement system rate, limiting and account lockout mechanisms, require users to use passwords with higher entropy (longer length) to compensate. |

6.3. Last, Resort Options and The Reality of Data Loss

If a user relies on a legacy cipher like ZipCrypto, third, party recovery tools often exploit the known algorithmic weaknesses to rapidly find the key. However, if the file was secured with a modern standard like AES-256, and the password is genuinely forgotten or lost, recovery is highly unlikely.

This reality is not a bug, it is the fundamental feature of strong encryption. Forgetting the key to strong encryption must be treated as permanent data loss. If the data were recoverable without the key, the encryption would be ineffective against unauthorized access. This reinforces the necessity of storing encryption passwords or keys securely within a dedicated password manager or robust offline backup system.

7. Strategic Deployment and Future, Proofing

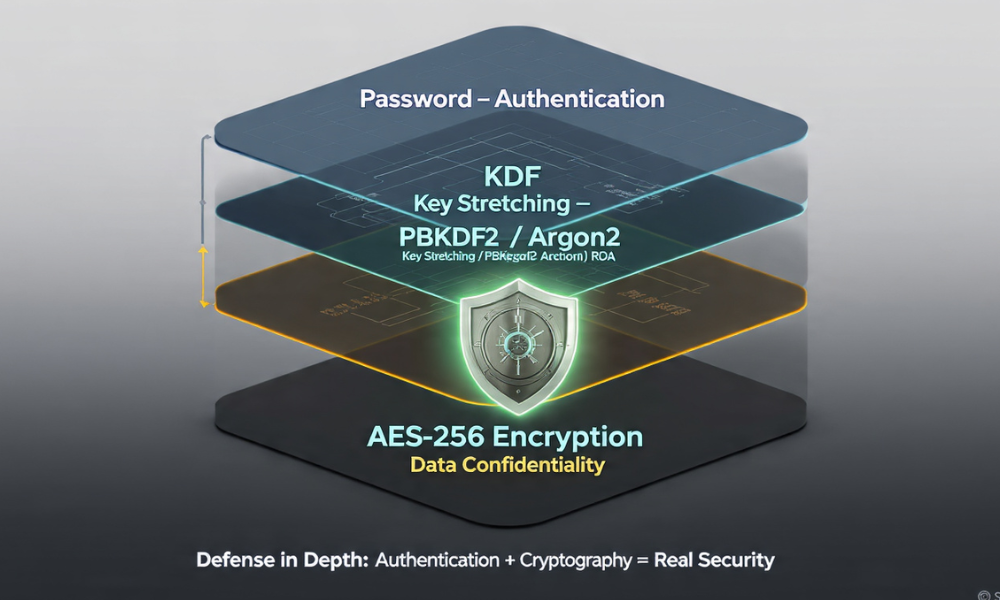

Securing data requires treating password protection and encryption not as interchangeable terms, but as complementary components in a defense, in, depth strategy.

7.1. Defense in Depth: Why We Use Both

The password (or passphrase) serves the crucial role of protecting the Key Derivation Function’s input. The KDF converts this human input into a cryptographic key. That key, in turn, protects the data itself using AES-256. If an attacker bypasses the initial password screen, the encryption ensures the data remains confidential. If the attacker gains the file, the KDF ensures that guessing the password required to unlock the key is computationally infeasible.

Effective security means ensuring both the authentication layer (password complexity) and the confidentiality layer (AES-256) are robust, and that the bridging technology (KDF iteration count) is configured to meet current hardware attack realities.

7.2. Hardware Acceleration and Modern Standards

The computational cost associated with strong encryption is mitigated in modern systems by hardware acceleration. Dedicated CPU instructions, known as AES-NI (Advanced Encryption Standard New Instructions), speed up the execution of AES algorithms. This acceleration allows legitimate users to encrypt and decrypt large files rapidly, while the high iteration counts set by KDFs still effectively throttle attackers who must perform complex computations for every password guess.

Looking forward, while PBKDF2 remains common in file archivers, the security community is actively promoting memory, hard functions such as Argon2. These next, generation KDFs are specifically designed to require not just processing power, but also large amounts of RAM during the key derivation process. This requirement intentionally defeats the efficiency of specialized GPU or ASIC hardware often used by professional attackers, offering superior protection against high, speed, parallel brute, force attacks compared to PBKDF2.

8. Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What happens if I forget the encryption password?

A: If the file was encrypted using a modern, strong algorithm like AES-256, forgetting the password means the data is likely permanently unrecoverable. Encryption is designed to make recovery impossible without the correct key, unlike simple password protection which may offer reset options.

Q: Does password-protecting a Word document count as true encryption?

A: Modern Microsoft Office files (2007 and newer) utilize strong AES-256 encryption. However, older file formats relied on critically weak, 40, bit RC4 encryption, which is trivially broken with readily available tools. Users must verify the format and underlying algorithm used.

Q: Why is AES-256 considered more secure than the older ZipCrypto?

A: AES-256 is a modern block cipher designed to resist known cryptographic attacks. ZipCrypto is a fundamentally flawed stream cipher vulnerable to known, plaintext attacks, allowing hackers to determine the internal key state and decrypt the file in a matter of hours, regardless of the password’s complexity.

Q: How can I tell if my system is vulnerable to brute-force attacks?

A: If your encryption implementation uses a Key Derivation Function (KDF) with an iteration count significantly below the OWASP standard of 600,000 rounds, it is highly vulnerable to rapid password guessing, especially from attackers using high, end graphics processing units (GPUs).

Q: Should I worry about the KDF iteration count if I use a very long, random password?

A: If your password is truly random and exceeds 25 characters, the overall entropy is so high that cracking remains infeasible, regardless of a lower KDF iteration count. The KDF primarily functions to protect users who rely on shorter, human, memorable passphrases against fast attack hardware.

Q: What is the primary job of a Key Derivation Function (KDF)?

A: The KDF converts a short, human, chosen password into a complex, high, entropy cryptographic key. Its primary job is to be computationally expensive (slow) to make automated brute, force attacks against the password infeasible.

Q: If I use 7-Zip, do I need to worry about metadata leakage?

A: Yes. By default, 7-Zip does not hide file names. You must explicitly select the “Encrypt file names” option when creating the archive, or attackers will see the contents list without the password.

Q: What is the difference between a TPM and the Secure Enclave?

A: Both secure FDE keys. The TPM (Windows/BitLocker) secures keys based on the system’s boot state (PCRs). The Secure Enclave (Mac/FileVault) is a dedicated, isolated processor with its own AES engine that protects keys even if the main macOS kernel is compromised.

Q: How does a Zero-Knowledge Cloud provider maintain data privacy?

A: ZK providers ensure the data is encrypted on the client’s device before it is uploaded. Since the encryption keys never leave the client, the provider only stores unintelligible ciphertext and cannot decrypt the data for anyone.

Q: Why does NIST recommend rotating cryptographic keys (cryptoperiods)?

A: Key rotation limits the exposure time of any single key. If a key is compromised, rotation ensures the attacker can only decrypt data covered by that key’s limited “cryptoperiod” (lifetime).

Q: If my data is unrecoverable due to a damaged VeraCrypt header, is the encryption still secure?

A: Yes. The encryption remains secure (confidential), but the data is inaccessible (loss of availability). This is a system integrity failure, not a cryptographic one. Backing up the volume header is the fix.

Q: Can I use AES-128 encryption instead of AES-256 for faster speed?

A: While AES-128 is technically strong, the speed difference is negligible due to AES-NI hardware acceleration. For maximum security, long, term archiving, and regulatory compliance, AES-256 is the mandated standard.

Q: Why are man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks a threat to E2EE?

A: E2EE is only secure if the endpoints are correctly authenticated. If a MITM attack compromises the initial key exchange (often due to an ignored security warning), they can substitute their own keys, breaking the E2EE chain.

Q: Does the GDPR Right to Erasure require me to physically destroy hard drives?

A: Not necessarily. If the data resides on a Full Disk Encrypted volume, securely deleting the volume’s master encryption key (cryptographic erasure) is a verifiable, efficient, and legally compliant method of irreversible data deletion that satisfies the Right to Erasure.

Conclusion

The analysis confirms that conflating password protection with cryptographic encryption represents one of the most significant security weaknesses in consumer and small business data handling. Password protection is merely an authentication gateway that can be bypassed or ignored by specialized software, leaving data exposed. True encryption, leveraging standards like AES-256, provides data confidentiality by fundamentally scrambling the information.

Implementation details, however, often introduce hidden vulnerabilities. The failure of systems like ZipCrypto and old Microsoft Office standards demonstrates that even the strongest passwords are useless against critically weak algorithms and key lengths. Furthermore, modern, robust ciphers like AES-256 can be undermined by insufficient key stretching. Tools that use fast KDFs (low iteration counts) significantly accelerate an attacker’s ability to guess passwords, forcing legitimate users to employ extreme password lengths just to compensate.

For highly sensitive data, organizations and individuals should move immediately to modern archiving tools (like 7-Zip) configured to use AES-256 encryption in the 7z format, ensuring the “Encrypt file names” option is enabled to protect metadata. When managing high, value client or proprietary data, relying on encryption architecture based on these high, standard KDF and AES parameters saves critical time and mitigates significant regulatory risk later on.