Modern Smartphone Encryption: iOS and Android Defaults and Limits

This technical overview, developed by Newsoftwares.net, details the core security paradox of modern smartphones: strong encryption is compromised for convenience the instant the device is unlocked. We examine the layered protection of the iOS Secure Enclave and Android’s File, Based Encryption (FBE) to explain why the “After First Unlock” (AFU) state is the greatest security weak point. This guide offers actionable steps to restore maximum security, ensuring your device’s data protection remains both robust and convenient.

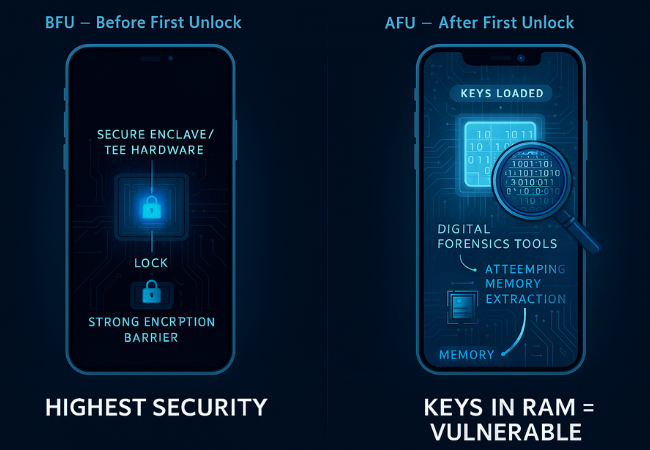

Modern smartphone security rests on a critical paradox: to ensure usability, phones must sacrifice their maximum level of data protection the instant the user unlocks the device. While manufacturers deploy state, of, the, art encryption ciphers, the true measure of security hinges on the device’s operational state, whether it is powered off, or actively processing data.

The greatest security weak point for modern devices is the transition from a highly secure, offline state to an active, usable one.

The State of Device Security

- Before First Unlock (BFU): Data is cryptographically secure. Decryption keys are stored in hardware and require the user’s full passcode to initiate derivation, often taking years of brute, force attempts to crack due to hardware rate limiting. This represents the device’s highest defense posture.

- After First Unlock (AFU): Crucial decryption keys, specifically the Credential Encrypted (CE) keys on Android and equivalent keys on iOS, are intentionally loaded and resident in volatile memory (RAM). This state is highly vulnerable to sophisticated physical forensic attacks, which can dump the memory contents and steal these resident keys.

- Actionable Defense: To guarantee the strongest possible protection, the device must be rebooted. Rebooting forces the system back into the BFU state, which demands a full passcode entry before any user data can be accessed.

I. The Core Architecture: iOS and Android Encryption Defaults

Understanding why unlocking the phone introduces risk requires a detailed look at the core encryption architectures used by Apple and Google. Both systems rely on dedicated hardware to manage key access, but their structural differences determine their unique vulnerabilities.

1.1. iOS Data Protection: Layered Security by Class

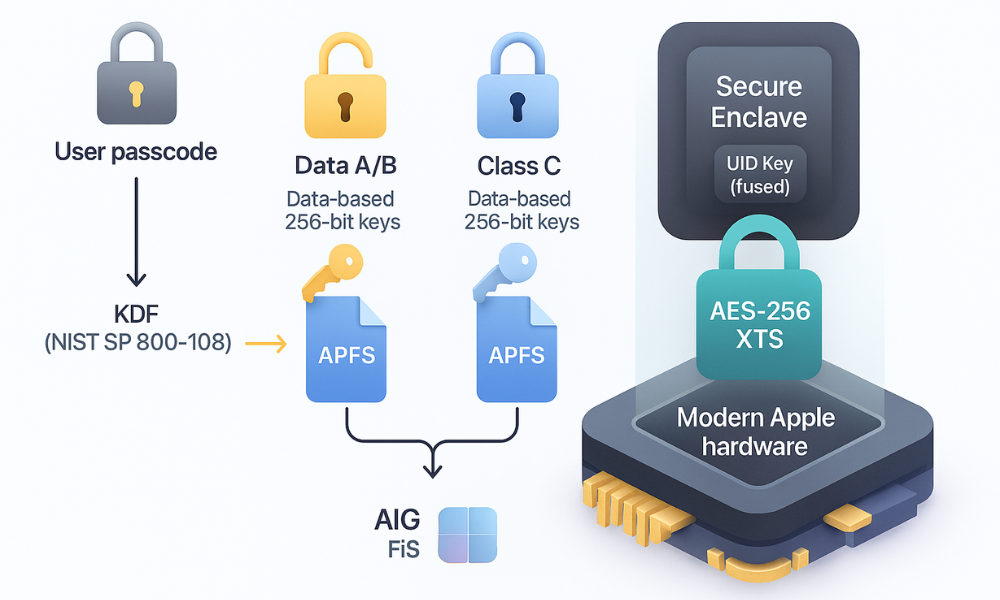

Apple implements Data Protection based on the Apple File System (APFS). This system employs a sophisticated key hierarchy that significantly complicates forensic extraction. Instead of relying on a single volume key, APFS creates a unique 256, bit per, file key for every file written to the flash storage. This structure forces an attacker to target millions of unique keys, providing a substantial defensive advantage.

The foundation of iOS security is the Secure Enclave, a dedicated subsystem that manages key derivation. The Secure Enclave fuses a unique User Identification (UID) key, burned into the hardware, with the user’s passcode. This combination runs through a robust Key Derivation Function (KDF), compliant with the NIST Special Publication 800, 108 standard. This KDF process securely stretches the user, supplied secret (the passcode) into high, quality cryptographic keys. This added complexity drastically mitigates offline brute, force attacks by increasing the time and computational resources needed for key derivation.

The Data Protection Class System

iOS determines data accessibility and security by assigning files to specific Data Protection classes. The security offered is directly related to the user experience trade, off: higher security means lower immediate availability.

- Class A/B (Highest User Security): Keys protecting this data are wiped from the Secure Enclave memory upon device reboot. This data requires full user authentication (passcode or biometric) after the reboot, making it the primary target of AFU memory extraction tools.

- Class C (Standard Protection): This is the default for many system files and third, party apps. Keys for this data remain available after the first unlock, persisting until the device is rebooted. This offers less immediate protection than the higher classes, prioritizing seamless operation once the user has entered their initial credentials.

For the encryption itself, newer devices (A14 and M1 Apple Silicon generations and later) use AES-256 in XTS mode. Older, but still modern, devices (A9 through A13) use AES-128 in XTS mode.

1.2. Android FBE: Separating Credentials and System Needs

Android uses File, Based Encryption (FBE), which succeeded the older Full Disk Encryption (FDE). The switch to FBE was necessary to support Direct Boot functionality, allowing the device to perform critical tasks like alarming or basic calling immediately after reboot, but before the user enters their passcode.

The Critical CE vs. DE Storage Split

FBE achieves Direct Boot by segmenting data storage into two partitions with different security requirements:

- Credential Encrypted (CE) Storage: This is the default location for private user data, including application data and private files. Access to this partition is strictly tied to the user’s lock screen PIN or password. The keys are only accessible after the initial user unlock.

- Device Encrypted (DE) Storage: This partition holds system files and data essential for Direct Boot mode. The keys protecting DE storage are bound to the hardware, specifically the Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) and Verified Boot process, rather than the user’s password.

The necessity of having DE keys available during Direct Boot means they are inherently less protected than CE keys. An attacker who manages to exploit a flaw in the device’s TEE execution environment, bypassing the need for a password guess, could potentially compromise DE storage even in the BFU state.

Secure FBE implementation is highly dependent on dedicated hardware:

- It requires KeyMint/Keymaster and Gatekeeper to be implemented within a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE).

- A Hardware Root of Trust mechanism, such as the Titan M security chip found in Pixel devices, is required. This root of trust ensures that the DE keys are not accessible if an unauthorized custom OS is loaded onto the device.

The security level across the Android ecosystem varies widely. While the default content encryption mode is typically AES-256-XTS, some manufacturers prioritize performance on devices lacking hardware AES acceleration. These devices may optionally utilize Adiantum encryption for content or metadata. While cryptographically secure, the choice to use Adiantum instead of AES-256-XTS is a clear example of prioritizing device speed over using the current maximum standard cipher.

Encryption Cipher and Use, Case Matrix

The following table defines the cryptographic choices made across the mobile landscape, highlighting the frequent security versus performance trade, off.

Encryption Cipher and Use, Case Matrix

| Cipher/Mode | OS Use Case | Primary Benefit | Security Context | Devices Targeted |

| AES-256-XTS | iOS (A14+), Android (Default Content) | Highest security, leverages dedicated hardware acceleration (AES-NI). | Standard for flagship devices, high theoretical resistance to known attacks. | Modern Flagship devices |

| Adiantum | Android (Option for Content/Metadata) | Efficiently fast on CPUs lacking hardware AES acceleration. | Strong protection, but explicitly chosen for performance optimization on lower, end hardware. | Mid, range and entry, level Android devices |

| NIST SP 800-108 KDF | iOS Key Derivation | Securely stretches user, supplied secrets into high, quality keys. | Mitigates offline brute, force attacks by increasing key derivation complexity. | All modern iOS devices |

| Hardware-Wrapped Keys | Android (Metadata/Keys) | Keys are encrypted and managed exclusively by the TEE/Titan M chip. | Keys are never exposed to the general OS kernel, preventing extraction even if the operating system is compromised. | Google Pixel devices, high, end Android flagships |

II. The Limits of Modern Encryption: Forensic Reality Check

If current encryption standards are so strong, why do commercial forensic tools continue to advertise success against the newest devices? The answer lies in the constant arms race between hardware security and software exploitation.

2.1. Zero, Days and the Accountability Gap

A zero, day is a security vulnerability unknown to the public or developers, meaning no patch exists to mitigate it. When these vulnerabilities are found and weaponized by threat actors or forensic companies, they can bypass the layers of defense built into the modern operating system.

The security landscape is further complicated by the tendency of smartphone manufacturers to downplay or conceal security flaws. This lack of transparency means users and IT administrators cannot accurately assess their risk profile. This concealment creates an extended window of vulnerability before necessary mitigations can be deployed.

2.2. Forensic Tools vs. Secure Hardware

Because hardware, based rate limiting makes brute, forcing a strong passcode in the BFU state computationally impossible, forensic companies have shifted their focus. Tools like Magnet GrayKey and Cellebrite consistently update their capabilities, providing full support for the newest operating systems, including iOS 17 and high, end devices like the Samsung S24 and Pixel 6/7 series, as of early 2024.

These tools exploit either low, level bootloader flaws or, more commonly, target the device while it is in the AFU state. The strategy is to exploit the running OS or related processes to dump the resident decryption keys from memory. The speed with which these tools update their capabilities confirms that relying solely on generic vendor security patches is insufficient. Users must adopt a defensive operational posture to counteract this reality.

Strong encryption forces investigators to acquire specialized, expensive tools and operate under specific warrant provisions. The continuous evolution of these tools ensures the ongoing legal and technical debate regarding cell phone privacy and search warrants remains active in jurisdictions like the US.

It is also important to note that encryption protects the file system, but it does not guarantee file erasure. Forensic processes can often recover data marked “deleted” by the user, including texts, photos, and GPS records, until the physical flash memory blocks are overwritten.

III. Actionable Security: Deep, Dive Isolation Tutorials

Enhancing security beyond the default AFU state requires the user to utilize specific isolation features designed to segment data and limit exposure.

3.1. Extreme Isolation: Activating iOS Lockdown Mode (How, To)

Lockdown Mode is designed for users facing highly targeted digital threats, such as state, sponsored spyware. It operates by severely restricting normal device functionality, thus drastically reducing the attack surface.

Prerequisites and Safety:

Lockdown Mode restricts message attachments, blocks complex web features like certain JavaScript or just, in, time (JIT) compilation, and disables specific conferencing inputs. This may break standard functionality for many apps and websites.

Steps:

- Open the Settings app.

- Tap Privacy and Security.

- Scroll down to the bottom, tap Lockdown Mode.

- Review the restrictions summary and tap Turn On Lockdown Mode, then confirm the selection.

- Tap Turn On and Restart, then enter the device passcode when prompted.

Gotcha:

To ensure a trusted, but restricted, website functions correctly, the user must manually exclude it. This is done by navigating to the website, tapping the Page Menu button, and turning off Lockdown Mode specifically for that domain. This configuration may not persist across all browsing sessions.

Verification:

Attempt to open a third, party app or a message containing a non, standard attachment (not a common image file). The system should block the content, confirming the mode is active and restricting inputs.

3.2. Android Isolation: Setting Up Samsung Secure Folder (How, To)

Samsung’s Secure Folder provides a localized, encrypted container for files and apps, separated from the main operating environment.

Prerequisites and Safety:

The Secure Folder requires a local Samsung account to enable the password reset function, which is critical for recovery. Files must be local, files saved on a Cloud account cannot be moved directly into the Secure Folder.

Steps:

- Navigate to Settings, tap Security and privacy, and then tap More security settings. Tap Secure Folder.

- Tap Continue to agree to permissions. Sign in to your Samsung account if prompted, and tap OK.

- Choose the security method (PIN, password, pattern, or biometric) and set the credentials. It is vital to ensure the Reset with Samsung account option is enabled at this stage.

- To move files: Open an application like Gallery or My Files, select the file(s) you want to move, tap More, then tap Move to Secure Folder.

Gotcha (Critical Vulnerability):

Secure Folder is architecturally based on the Android Work Profile framework. If the user has a separate corporate or third, party Work Profile active (using an MDM solution or an application like Island), apps running in that secondary profile may gain unauthorized access to the contents of the Secure Folder due to known policy misconfigurations.

Verification:

Open the Secure Folder and confirm the moved files are visible only within that container. Check the Quick Settings panel to ensure the Secure Folder toggle is active and accessible.

3.3. Enterprise Isolation: Creating a Generic Android Work Profile (How, To)

A generic Android Work Profile provides robust isolation used primarily for corporate security, segmenting enterprise data from personal applications.

Prerequisites and Safety:

This requires enrollment through a Google Workspace account or a Mobile Device Management (MDM) solution. The profile grants the organization’s IT administrators control over the contained apps and data, including policy enforcement and remote wipe capability.

Steps:

- In the device settings, begin the process of adding a new work or school account (Google Workspace).

- Enter the Google Workspace email address and password.

- Accept the necessary Terms of Service and Privacy Policy. When prompted, tap Accept and continue to create the dedicated work profile container.

- Follow the prompts to set a screen lock specifically for the Work Profile. This lock is managed separately from the personal device lock.

Verification:

Confirm that all newly installed work applications display a small briefcase icon overlay. This indicates they are running within the separate, segmented work profile container, isolating their data from the personal side of the device.

IV. Troubleshooting and Edge Cases

When utilizing advanced encryption features, users frequently encounter errors that stem from hardware failure, credential loss, or device integrity checks.

4.1. Secure Folder Access and Integrity Failures

Secure Folder errors typically arise from three primary causes: the loss of user credentials, a failure of the device integrity check (often associated with rooting), or a critical failure of the underlying storage hardware.

4.2. Troubleshooting Secure Container Errors

The reliance on the Samsung account for Secure Folder password reset, while convenient, introduces a critical security trade, off. This linking creates a single point of failure that, if compromised, could grant an attacker access to the “secure” container by bypassing the local PIN or pattern.

Troubleshooting Secure Folder and Device Integrity

| Symptom/Error String | Root Cause | Non, Destructive Test | Last Resort (Data Loss Warning) |

| Secure Folder password forgotten. | Credential loss, biometric fallback failure. | Attempt the Forgot option on the prompt and reset using the linked Samsung account credentials. | Seek expensive, dedicated forensic recovery service, minimal chance of success. |

| Secure Folder “unable to lock” or icon is grayed out. | Application hidden or failure to initialize. | Check the Quick Settings panel for the icon. Verify files exist via My Files > Internal Storage > Download > Secure Folder. | Uninstall and immediately reinstall Secure Folder. Warning: Data stored inside will be lost. |

| Cannot access data, Secure Folder locked automatically. | Device integrity compromised (e.g., rooted or running custom ROM). | Run a proprietary hardware health check (e.g., Samsung Knox Status check). | Factory reset the device to restore official firmware. Data in Secure Folder is likely permanently inaccessible. |

| Android displays: “Encryption unsuccessful.” | Critical failure of internal memory (EMMC chip) or corrupted storage. | Attempt to boot into Recovery Mode (using Power/Volume combinations) to check system logs for hardware faults. | Immediately back up all accessible data, then perform a full Wipe Data/Factory Reset via Recovery Mode. If the error persists, the EMMC chip needs professional replacement. |

The “Encryption unsuccessful” error demonstrates that the security promised by file, based encryption is entirely dependent on the physical health of the flash storage. If the EMMC memory chip fails, the encrypted data cannot be read, proving that encryption relies on a functional hardware foundation, not merely software ciphers.

4.3. Known Architectural Weakness: The Work Profile Overlap

Samsung’s implementation of Secure Folder relies on policy, based segregation. This architecture is sometimes inadequate when a second, independently managed Work Profile (such as one deployed by corporate MDM) is running simultaneously. This scenario creates a data path bypass, allowing applications within the second Work Profile to view and potentially access files stored in the Secure Folder.

If a device is used for both highly sensitive personal data (in Secure Folder) and corporate functions (Work Profile), users must assume the corporate administrator may have potential, unintended visibility into the Secure Folder contents. The only effective mitigation is to run the Secure Folder on a device that is not actively managed by any other corporate or third, party Work Profile framework.

V. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Does turning my phone off protect my data

Yes. Rebooting the device is the single most effective operational defense. It forces the device back into the BFU state, clearing the essential decryption keys from RAM and making hardware memory extraction virtually impossible without a zero, day exploit.

2. How long is my phone vulnerable after I unlock it (AFU)

The device remains vulnerable to sophisticated forensic tools as long as it remains powered on and unlocked. The AFU vulnerability persists until the device is explicitly powered down or rebooted.

3. Does backing up to Google Drive or iCloud bypass device encryption

Yes. Device encryption only protects the local storage. Once data is transferred to the cloud, it is protected by the cloud provider’s security architecture, which is independent of your local device’s hardware key chain.

4. Are biometrics (Face ID/Fingerprint) safer than a passcode

Biometrics serve as a convenience layer, authorizing the immediate release of the key derived from your primary passcode. They do not introduce a stronger cryptographic layer, only a faster AFU trigger.

5. Is Adiantum encryption safe if it’s designed for slow CPUs

Adiantum is considered cryptographically secure and was designed by Google to optimize performance. Its use means the manufacturer prioritized device speed over using the absolute maximum standard (AES-256-XTS).

6. Can files I delete inside Secure Folder ever be recovered

Deleted files may persist on the physical disk until the memory blocks are overwritten. Recovery is extremely difficult, usually requiring costly forensic services, even for the original owner.

7. What is Direct Boot mode in Android

Direct Boot mode is the operational state immediately after reboot and before the user enters their password. It relies on Device Encrypted (DE) storage to maintain critical functions like phone calls and alarms.

8. If I root my phone, does FBE still work

Rooting compromises the Verified Boot process and the hardware root of trust. This invalidates the trust chain required by FBE and applications like Secure Folder, causing them to lock up to prevent unauthorized access.

9. What is a hardware, wrapped key

A key wrapped by hardware is encrypted by a master key stored deep within the TEE/Secure Enclave. The wrapped key is only ever unwrapped and used within the secure hardware boundary, protecting it from general OS compromise.

10. How does iOS Data Protection Class C differ from Class A

Class A data requires the user’s passcode or biometric after a reboot, offering maximum security. Class C data is available earlier after the first unlock, relying more heavily on the underlying device key hierarchy.

11. Do modern security chips like Titan M truly prevent extraction

Chips like Titan M significantly increase the difficulty of extraction by forcing attackers to target the TEE firmware itself or require expensive zero, day bootloader exploits, making BFU attacks impractical for typical threat actors.

12. Can law enforcement force me to provide my password

While warrants are required to search a phone’s contents, legally compelling a user to provide a password or PIN remains a complex legal issue, often dependent on jurisdiction and precedents regarding self, incrimination.

13. Why do I need a Work Profile if I already have Secure Folder

Secure Folder is a consumer utility for data segregation. A Work Profile is an enterprise feature designed for IT administration, allowing managed policy enforcement and remote wipe capability, which Secure Folder lacks.

14. Does using a VPN protect my data against encryption exploits

A VPN protects data in transit (network traffic). It offers no protection against an attacker who gains physical access and exploits the device’s internal encryption system in the AFU state.

15. How can I check if my Android device’s encryption is hardware, backed

Checking for features like hardware wrapping (e.g., wrappedkey_v0) often requires using technical commands (adb shell) or system information apps, as manufacturers rarely disclose this level of detail in consumer settings.

VI. Conclusion

Modern smartphone encryption represents a deliberate and necessary compromise between absolute security and daily usability. Dedicated hardware roots of trust and trusted execution environments provide robust protection when the device is locked or powered off (BFU state). This powerful defense successfully forces specialized forensic tools to focus their efforts on memory, resident keys accessible immediately after the initial unlock (AFU state).

The critical difference between BFU security and AFU security is time, the expensive, dedicated computational time required to crack the passcode is replaced by the relatively short time required to exploit a running operating system. For the average user, hardware, backed encryption offers powerful protection against opportunistic theft. However, for users facing targeted digital threats, the operational posture must shift. Strong encryption is merely a barrier that buys time and raises the cost of exploitation. The simplest and most effective defense remains powering down or rebooting the device when privacy is paramount, forcing a return to the cryptographically secure BFU state.