HTTPS/TLS vs. End-to-End Encryption: The Lock Icon Demystified

This executive guide, created by the security experts at Newsoftwares.net, provides the definitive distinction between transport and End-to-End security. The HTTPS lock icon confirms your connection to the server is secure, it verifies the server’s identity via Transport Layer Security (TLS). Crucially, this verification does not mean the service provider or server owner cannot read your data. End-to-End Encryption (E2EE), however, ensures that only the intended recipient’s device, and not the intermediary service provider’s server, can ever decrypt the message. This difference defines the trust boundary and who ultimately controls your privacy, ensuring verifiable data confidentiality and service integrity.

The definitive distinction is simple: The HTTPS lock icon confirms your connection to the server is secure, it verifies the server’s identity via Transport Layer Security (TLS). Crucially, this verification does not mean the service provider or server owner cannot read your data.

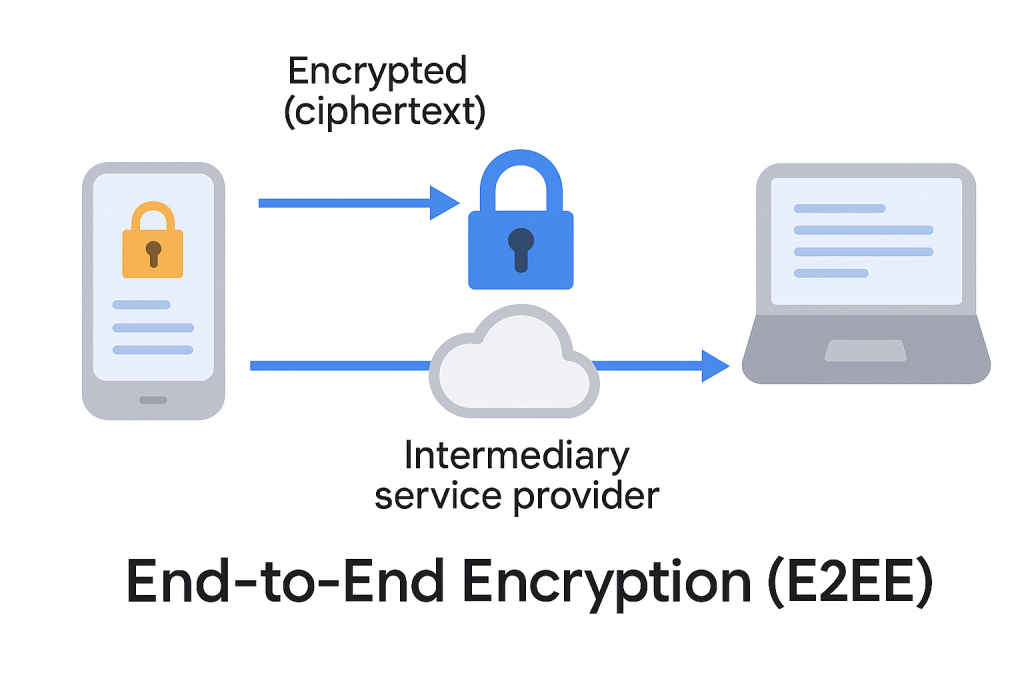

End-to-End Encryption (E2EE), however, ensures that only the intended recipient’s device, and not the intermediary service provider’s server, can ever decrypt the message. This difference defines the trust boundary and who ultimately controls your privacy.

The Padlock Paradox: In, Transit Security vs. Endpoint Secrecy

For most people, seeing the padlock in the address bar is the universal signal for safety. This signal confirms that the data traveling from your browser to the website’s server is shielded from interception by outsiders, such as hackers on your local coffee shop Wi, Fi or your internet service provider. This is the core promise of HTTPS, which is HTTP layered upon TLS.

However, the trust ends the moment the data reaches the server. Once there, the data must be decrypted into plaintext so the service provider can read it, process the transaction, deliver the content, or save it to a database. The critical realization here is that the service provider, whether it is Google, your bank, or a social media platform, has full access to the content.

The boundary established by standard TLS is client, to, server. This design fundamentally re, allocates organizational accountability. When a company relies only on TLS, it possesses the user’s plaintext data. This places the organization under strict scrutiny regarding regulations like HIPAA or GDPR, making them liable for the security of that data both in transit and at rest.

Conversely, E2EE shifts the point of trust. Since the service provider handles only undecipherable encrypted data (ciphertext), they cannot provide message content even if served with a regulatory subpoena, significantly limiting their exposure and protecting users from certain government data requests.

Table 1: TLS (HTTPS) vs. End-to-End Encryption (E2EE) Comparison

| Security Model | Decryption Location | Service Provider Access to Plaintext | Primary Security Goal |

| HTTPS/TLS | Server Side | Yes (required for processing/storage) | Transport integrity and server authentication |

| E2EE | Recipient Device Only | No (Only relays ciphertext) | Absolute user privacy and data secrecy |

Transport Security Deep Dive: Decoding the TLS Lock and Handshake

HTTPS layers standard HTTP on top of TLS (Transport Layer Security), which is the successor to SSL (Secure Sockets Layer). The essential role of TLS is two, fold: first, to verify the server’s identity via a trusted Certificate Authority (CA), and second, to establish rapid, encrypted session keys for the subsequent data transfer. The limitations of HTTPS are structural, rooted in this design which necessitates server decryption.

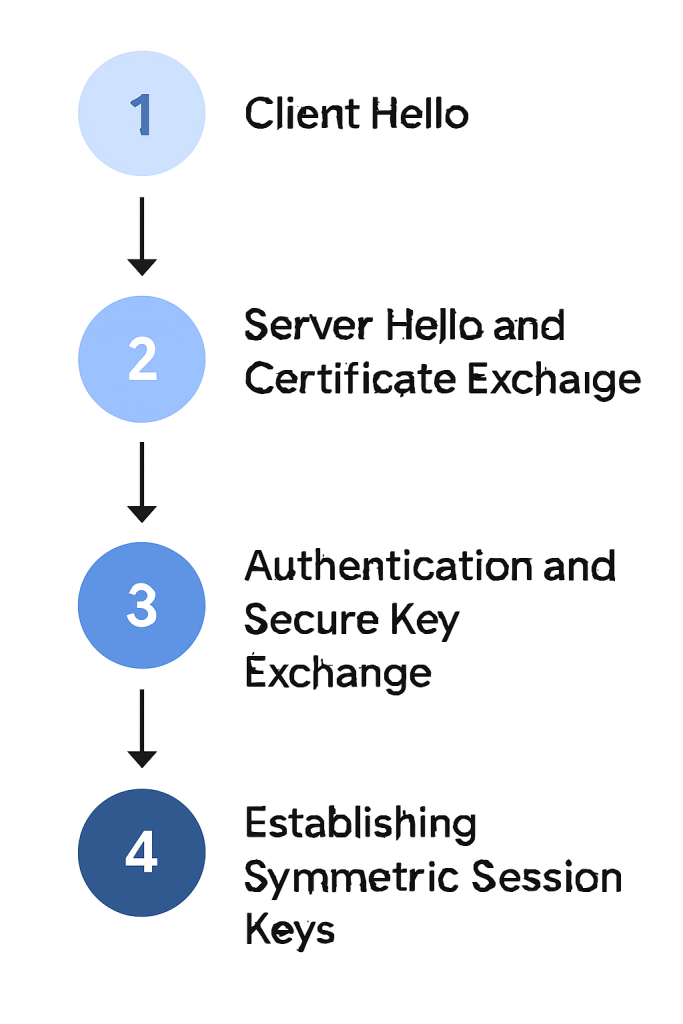

Protocol Tutorial: The Four Stages of the TLS Handshake

The TLS handshake is a complex, four, step choreography executed in milliseconds before any application data is sent. It is the cryptographic agreement that establishes the secure session. The precise steps can vary slightly depending on the specific key exchange algorithm chosen, but the core process is standardized.

- Step 1: The Client Hello Message:

Action: The client’s browser begins the process by sending a ‘hello’ message to the server. This message includes the TLS version the client supports, a prioritized list of supported cipher suites (like AES-256 or ChaCha20), and a string of random unique data known as the “client random”.

- Step 2: The Server Hello and Certificate Exchange:

Action: The server replies, acknowledging the client. The response contains the server’s chosen TLS version and the best matching cipher suite from the client’s list. Crucially, the server also sends its SSL/TLS certificate, issued by a trusted CA, and a second random unique string, the “server random”.

- Step 3: Authentication and Secure Key Exchange:

Action: The client uses the server’s certificate to perform two mandatory checks. First, it verifies that the certificate is signed by a CA that the client trusts. Second, it confirms that the domain name listed on the certificate matches the domain the client is trying to connect to. If the certificate is valid, the client and server execute a key exchange method (such as Diffie, Hellman) using asymmetric public/private key cryptography. This exchange securely derives a shared secret that both parties now possess.

- Step 4: Establishing Symmetric Session Keys:

Action: Both the client and server use the shared secret, the “client random,” and the “server random” to independently generate identical session keys. These symmetric keys are extremely efficient and are used to encrypt and decrypt all data for the remainder of the session. Both parties send a final confirmation message signaling that the secure channel is officially established.

This multi, step process explains why the old myth that “SSL slows down the internet” is untrue. The initial cryptographic heavy lifting (asymmetric encryption) is minimal and only happens once per session during the key exchange phase (Steps 1, 3). After that, the system switches to the significantly faster symmetric session keys, maximizing speed for high, volume data transfer.

A key security feature of modern TLS, especially when using protocols like Elliptic Curve Diffie, Hellman (ECDHE), is Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS). This feature ensures the symmetric session keys used in Step 4 are temporary and unique. Should an attacker compromise the server and steal its long, term private key at a later date, they still cannot use that key to decrypt recorded past session traffic, as the temporary session keys were discarded after use.

The entire TLS system relies entirely on the integrity of the Certificate Authority (CA). The CA is the single point of trust in this model. If a CA were compromised or acted maliciously, an attacker could obtain a valid, browser, trusted certificate for any high, profile site. This would enable a highly sophisticated Man, in, the, Middle attack that the user’s browser would still incorrectly flag as secure.

Actionable Steps: Checking and Verifying Your TLS Connection

Simply observing the lock icon is not sufficient proof of security. Users must verify the certificate details, the issuer, the domain match, and the expiration date, to confirm the server’s valid identity proof from the CA.

Tutorial 1: Verifying the SSL Certificate in Major Browsers

Checking the certificate expiration date is a vital, immediate troubleshooting step. An expired certificate immediately terminates the TLS handshake. Many common connection errors stem from administrators neglecting certificate renewal, a common administrative oversight that a robust Certificate Lifecycle Management (CLM) solution helps mitigate.

Chrome/Edge Walkthrough (Developer Tools Method)

- Action: Load the HTTPS website.

- Action: Open the browser menu (the Three, Dot icon) to the right of the address bar.

- Action: Navigate to More Tools > Developer Tools.

- Action: In the Developer Tools panel that opens, select the Security tab.

- Action: Review the Security Overview and click View Certificate.

- Verification Check:

Verify: Ensure the certificate’s

Issued Todomain matches the site you are visiting exactly, and verify that the certificate has not expired.

Firefox Walkthrough (Preferences Method)

- Action: Click the Firefox menu and select Preferences (or Settings).

- Action: Open the Privacy and Security panel.

- Action: Scroll down to the Certificates section.

- Action: Click View Certificates to open the Certificate Manager, allowing inspection of all accepted certificates.

The certificate acts as a digital passport. Verification confirms that the entity claiming to be example.com was legitimately authenticated by a global trust authority.

The Trust Gap: Where Data Becomes Vulnerable with TLS

The fundamental vulnerability of TLS lies in its requirement for server, side decryption. The data transfer is secure, but the destination, the web server, is not the final, private recipient. The server must use the derived symmetric session key from the handshake to decrypt the data stream. This decryption is necessary for the application layer to read the content, process the request (e.g., executing a database lookup), and potentially write the plaintext data into storage.

Server Control: The Plaintext at Rest Problem

Once the data is decrypted on the server, its security relies entirely on the service provider’s internal infrastructure and security policies. HTTPS provides protection against Layer 3/4 threats (network, level eavesdropping), but it offers no defense against Layer 7 (application, level breaches).

For instance, an attacker on a local Wi, Fi network cannot read the TLS traffic, but a malicious insider administrator at the website hosting company or an external hacker who exploits a web application vulnerability can read the data once it is decrypted on the server.

The data is now vulnerable to several critical points of failure:

- Internal Threats: Data is exposed to rogue employees or insider actions.

- Regulatory Disclosure: The platform possesses the plaintext, making it immediately subject to government subpoenas or legally binding disclosure requests.

- External Compromise: A breach allows an attacker to access the server’s memory, file systems, or database, where the plaintext data resides.

Relying solely on TLS can encourage dangerous complacency among developers and administrators regarding internal data security controls. The effort put into securing the transport layer (TLS) must be mirrored by robust at, rest encryption and strict access control on the server side, a necessity often forgotten because the assumption is that “the data is encrypted,” even though it is only encrypted in transit. The lock icon, in this context, provides a false sense of comprehensive security regarding the integrity of the server itself.

End-to-End Encryption: Achieving True Secrecy

E2EE fundamentally changes the trust model by ensuring data is encrypted on the sender’s device and remains ciphertext, even when passing through the service provider’s server, only decrypting at the recipient’s device.

E2EE Fundamentals: Client, Side Key Generation

E2EE utilizes asymmetric cryptography (public/private keys). The critical difference from TLS is that the private key, the only tool capable of decryption, is generated and held exclusively by the user on their device.

The service provider’s role is reduced to acting as a secure relay. It handles the exchange of public keys and transports the encrypted data. The server never sees the private key, thus, encrypted data relayed through the service provider is indecipherable to them.

The Gold Standard: The Signal Protocol Architecture

The Signal Protocol has become the technical benchmark for E2EE, providing robust security primitives adopted by major services, including WhatsApp, Google Messages, and optional “Secret Conversations” in Facebook Messenger.

Key architectural components include:

- Double Ratchet Algorithm: This highly sophisticated mechanism continuously generates new cryptographic keys for every message or message batch. This provides Forward Secrecy (if a current key is compromised, past messages remain secure because their keys were destroyed) and Future Secrecy (a known key does not allow prediction of keys used in future messages).

- Key Exchange: Initial secure key agreement uses a Triple Elliptic, Curve Diffie, Hellman (3, DH) handshake, often combined with prekeys (one, time ephemeral public keys uploaded in advance to the central server).

E2EE Trade, offs: The Cost of Maximum Privacy

While E2EE guarantees maximum data privacy, it imposes functional trade, offs that limit features requiring server interaction with plaintext data.

For example, when enabling E2EE in Zoom meetings, certain features are automatically disabled, including cloud recording, centralized polling, live transcription, and AI Companion features, because these require the server to be able to read and process the audio or chat data.

Beyond feature loss, E2EE also complicates traditional application functions. Server, side indexing for search (like in traditional email) becomes impossible. Effective solutions require complex, client, side searchable encryption, which adds technical complexity to the application.

It is also important to note that E2EE platforms still have access to, and store, metadata. While the message content is fully protected, the server still records who messaged whom, when, and how often. This metadata can be highly revealing about user connections and communication patterns, yet it is not protected by the E2EE protocol itself.

User Verification: Ensuring You Are Talking to the Right Endpoint

Because E2EE bypasses the trusted third, party verification of the CA system, a crucial human, centric step is required: key fingerprint verification.

The Critical Step: Key Fingerprint Verification

Without a CA to vouch for the public key, users must manually confirm the authenticity of the public key they received from their contact. This process is essential to prevent a simple Man, in, the, Middle (MITM) attack where an attacker attempts to swap their own public key in place of the intended recipient’s. If the attacker successfully introduces their key, they can decrypt, read, re, encrypt, and forward the message without either party realizing they are compromised.

Tutorial 2: Using System Key Verifiers and Security Codes (E2EE Proof of Work)

- Locate Verification Code:

Action: Within the secure messaging application, users must access the contact details or security settings to display the unique security code or cryptographic fingerprint (often a sequence of digits or a QR code) derived from their shared keys.

- Comparison:

Action: The code must be securely transmitted or verbally confirmed with the recipient. If the codes match, it constitutes cryptographic proof that the users are communicating directly and securely.

- System Assistance:

Action: To address the inconvenience of manual verification, systems like the Android System Key Verifier have emerged. These services help developers store and unify public key verification across compatible E2EE applications, making it easier for users to confirm they are communicating with the intended party.

The success of E2EE depends entirely on user behavior, the human factor is the weakest link. Because manual key verification is inconvenient, many users skip it, opening a vulnerability if the central key server responsible for key distribution were ever compromised.

Performance and Protocol Modernization (The Cipher Debate)

A long, standing argument against heavy security protocols was performance overhead. However, modern TLS has largely dispelled this myth. Production benchmarks show that the cryptographic load associated with TLS is minimal, often accounting for less than 1% of CPU usage and minimal memory overhead per connection.

Deep Dive: Stream Ciphers vs. Block Ciphers in TLS 1.3

The choice of symmetric cipher affects performance and implementation resilience, particularly in varied environments. Modern crypto engineering often focuses less on the absolute security level (as both ciphers below offer 256, bit security) and more on implementation security and consistent performance across diverse hardware.

- AES-256 (GCM): This is a block cipher that performs exceptionally well when hardware acceleration is available. Most modern processors (e.g., Intel AES-NI) include dedicated instructions that make AES extremely fast for disk encryption and high, end server processing.

- ChaCha20-Poly1305: This is a stream cipher optimized specifically for software implementation using general CPU instructions (SIMD). It excels in TLS 1.3 protocols, offering superior performance on resource, constrained devices, mobile platforms, or large cloud instances lacking dedicated AES hardware. It also offers a higher “safety margin” and is less prone to implementation mistakes than software, implemented AES.

A high, quality system will dynamically negotiate between AES-256 (if hardware acceleration is detected) and ChaCha20, maximizing throughput regardless of the client or server hardware. ChaCha20’s primary practical advantage is its predictable, fast performance across heterogeneous CPUs, mitigating the risk of timing attacks often associated with poorly implemented AES in software.

Table 2: Modern Cipher Comparison for High, Volume TLS

| Cipher Suite | Mechanism Type | Primary Optimization | Performance Benchmark Context | Implementation Advantage |

| AES-256 (GCM) | Block Cipher (Authenticated) | Dedicated Hardware (AES-NI) | Fastest option on high, spec servers/laptops with hardware acceleration. | Standard for compliance and enterprise environments. |

| ChaCha20-Poly1305 | Stream Cipher (Authenticated) | General CPU (Software/SIMD) | Superior performance for TLS 1.3 on mobile, embedded, or unaccelerated cloud instances. | Higher safety margin, less prone to implementation errors in software. |

Troubleshooting Connection Integrity

When the padlock icon fails or connection errors occur, the problem often traces back to configuration oversights or the exploitation of legacy insecure protocols by attackers. Attackers routinely exploit insecure server setups through methods like SSL Stripping and Downgrade attacks, which force connections back to insecure HTTP.

Immediate Fixes: Enforcing HSTS and Disabling Legacy HTTP

- Enforce HSTS (HTTP Strict Transport Security):

Action: Server administrators must implement the

Strict-Transport-Securityheader. This header forces browsers that have visited the site previously to only use HTTPS, preventing the client from ever initiating a connection over insecure HTTP, even after redirects. - Disable HTTP:

Action: Enforce HTTPS, only settings directly on the web server to completely eliminate the possibility of clients connecting over the insecure protocol.

The most common and often overlooked cause of a perceived “broken” secure connection is a Mixed Content Warning. If 99% of a page is secure, but a single resource, such as a small image or a CSS file, is loaded over an insecure http:// link, the browser correctly degrades or removes the lock icon. Troubleshooting these issues requires meticulous debugging via console logs to find the specific insecure references.

Server security failures are often administrative oversights rather than technological limitations. TLS vulnerabilities frequently exploited, such as expired certificates or downgrade attacks, are policy failures. Implementing Certificate Lifecycle Management (CLM) and enforcing strict headers are policy fixes that leverage existing, robust technology to eliminate these administrative risks.

Table 3: TLS/HTTPS Connection Error Symptoms and Fixes (Troubleshooting)

| Symptom / Exact Error Message | Root Cause | Non, Destructive Fix (Client) | Last Resort Fix (Server Administrator) |

| Padlock is missing or marked insecure (Yellow/Red). | Mixed Content Warning: Insecure http:// resources (images, scripts) are loaded on an https:// page. |

Action: Use browser Developer Tools console to locate the specific insecure resource link path. | Enforce Content Security Policy (CSP) and update all resource paths to relative URLs or https://. |

| Connection reset, ‘503 Service Unavailable’, or ‘TLS handshake failed’. | Expired certificate, system clock error, or severe mismatch in cipher suites. | Action: Correct system date/time. Clear browser cache and check proxy settings. | Renew the certificate immediately. Ensure the server supports modern TLS versions (1.2/1.3) and modern ciphers. |

| Browser reports security error after manual typing, even though HTTPS is expected. | Possible SSL Stripping attack or lack of HSTS enforcement. | N/A (The core fix must be server, side enforcement). | Implement HSTS headers and ensure redirect rules are properly managed using a Certificate Lifecycle Management solution. |

Strategic Implementation: Choosing the Right Security Model

Choosing between TLS and E2EE requires mapping the data’s sensitivity against the necessity for server, side processing. If data needs to be aggregated, indexed, or analyzed by the service (e.g., e, commerce order processing), TLS is the default choice, placing trust and liability on the service provider. If the goal is absolute, zero, knowledge privacy from the platform itself, E2EE is mandatory.

For complex applications, this requires embracing a “zero, knowledge” application architecture. Instead of building features like indexing and search on the server, E2EE forces the data and computation to the client device. This architectural constraint guarantees privacy but demands significantly more sophisticated client, side engineering.

Many platforms adopt a hybrid approach: using TLS for public, facing assets and administrative access, while reserving E2EE for specific, sensitive communication channels or data storage, balancing performance and privacy requirements.

Table 4: Security Model Selection by Use Case and Risk Tolerance

| Use Case | Service Provider Trust Required? | Core Requirement | Recommended Model | Reasoning |

| E-Commerce Checkout | High (for payment processing, fulfillment) | PCI Compliance | HTTPS/TLS | The merchant must decrypt and process financial details, trust is placed in the merchant’s regulated environment. |

| Personal Secure Messaging | None (goal is privacy) | Absolute Secrecy from Platform | E2EE (Signal Protocol) | High risk of surveillance or subpoena requires the service provider to be structurally excluded from message content. |

| Medical Record Sharing (Platform) | None (goal is HIPAA compliance/Zero, knowledge) | Client, side Encryption | E2EE | Legal mandates often require that the hosting platform cannot view Protected Health Information (PHI). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the difference between HTTPS and E2EE

HTTPS (TLS) secures the transport layer, encrypting data between your device and the server. E2EE secures the application layer, encrypting data directly between devices, ensuring the server cannot read the content.

2. Is WhatsApp truly End-to-End encrypted

Yes. WhatsApp utilizes the Signal Protocol, which employs advanced key management mechanisms, including the Double Ratchet Algorithm, to ensure that messages, calls, photos, and videos are only decipherable by the sending and receiving endpoints.

3. Does the green lock icon mean a website is safe to trust

No. The lock icon guarantees that the connection is encrypted and the site’s identity is verified by a Certificate Authority. It confirms transport security but does not vouch for the website’s honesty, reputation, or internal security against hackers.

4. What limitations result from enabling End-to-End Encryption

E2EE disables features that require the service provider to access and process the message content in plaintext. This commonly includes cloud recording, server, based AI features, live transcription, and centralized polling functionality.

5. Is ChaCha20-Poly1305 safer than AES-256

Both are cryptographically sound 256, bit ciphers. ChaCha20 is often preferred in software, only contexts (mobile, low, power servers) due to its superior speed and resistance to timing attacks when hardware acceleration (AES-NI) is not available, offering greater implementation consistency.

6. How do I fix a Mixed Content Warning error

Administrators must locate and change any residual http:// links within the site’s source code (typically for scripts, images, or CSS) to use https:// or relative URLs. The browser’s console logs (Developer Tools) will precisely pinpoint the insecure resource.

7. Why do I need to verify E2EE security codes

Since E2EE bypasses central Certificate Authorities, users must manually compare the cryptographic key fingerprint with the recipient. This prevents a potential Man, in, the, Middle attacker from substituting their own public key into the exchange, preserving endpoint identity.

Conclusions

The primary finding is that the browser padlock, the symbol of HTTPS/TLS, guarantees connectivity security but fundamentally misrepresents data privacy. TLS successfully secures the pipe but requires the destination server to open the contents. This structural requirement places user data entirely at the mercy of the service provider’s internal security and regulatory environment.

For users and organizations where data sensitivity is paramount, such as in healthcare or private communications, E2EE is not merely an optional security layer but a foundational architectural necessity. While E2EE imposes constraints on feature design, it is the only mechanism that reliably achieves true endpoint secrecy. Understanding this boundary of trust is the most critical step in evaluating and deploying modern security protocols.