Encryption Frequency: When, Why, and How to Secure Files, Drives, Emails, Backups, and Cloud Data

This comprehensive overview, developed by Newsoftwares.net, establishes that encryption must be continuous and policy, driven, not occasional. It should be mandatory and applied based on the data’s classification and its current state, At Rest, In Transit, or In Use. For any data requiring confidentiality, the acceptable answer is to always encrypt across the entire data lifecycle. This continuous approach is necessary to satisfy modern compliance demands and prevent catastrophic data exposure, ensuring both security and user convenience.

Encryption must be continuous and policy, driven, not occasional. It should be mandatory and applied based on the data’s classification and its current state, At Rest, In Transit, or In Use. For any data requiring confidentiality, the acceptable answer is to always encrypt across the entire data lifecycle.

This continuous approach is necessary to satisfy modern compliance demands and prevent catastrophic data exposure.

Encryption Checklist Summary

- Rule of Thumb: If data is Restricted or Confidential (e.g., PII, IP, Financial records), it must be secured using NIST, approved algorithms like AES-256, consistently throughout its storage and transmission.

- For Devices: Use Whole Disk Encryption (WDE) such as BitLocker or FileVault to protect against device loss or theft. This is essential for any mobile device, including corporate laptops.

- For Cloud: Avoid relying solely on provider, side keys. Always use Client, Side Encryption (CSE), typically through tools like Cryptomator, before uploading sensitive files to public services like Google Drive or Dropbox.

- For Keys: The encryption is only as secure as the key. Prioritize key backup redundancy (offline copies) and use modern, memory, hard key derivation functions (KDFs) like Scrypt to protect against brute, force attacks.

1. Defining the “When”: Policy, Data States, and Frequency

Security professionals recognize that data security is not achieved by encrypting a file once, but by maintaining cryptographic protection as the data moves through its organizational life cycle. This continuous requirement is defined by two factors: data classification and the data’s state of being.

1.1. The Critical Policy: Data Classification Dictates Obligation

Organizations cannot properly manage encryption without first classifying their data based on sensitivity. This process determines the necessary level of technical control. Data is typically classified into high, medium, or low sensitivity levels, corresponding to the potential impact if the data were compromised.

High sensitivity data includes financial records, intellectual property, and authentication data. If compromised, this data results in a catastrophic impact on the organization or individuals. Consequently, such data demands encryption both at rest (DAR) and in transit (DIT). Conversely, low sensitivity data, such as public website content, primarily requires only integrity checks during transmission.

NIST Special Publication 800-171 mandates that all data requiring confidentiality protection should be encrypted whenever there is a possibility that an unauthorized person could gain access. This applies not only to data actively used in the operational environment but also to all copies, including data stored in backup environments. Furthermore, if data was previously encrypted using an obsolete algorithm, it must be re, encrypted using current NIST, approved encryption functions. The commitment to encryption is thus an ongoing commitment to modern standards.

Data Classification and Encryption Requirement Table

| Sensitivity Model 1 | Impact of Compromise | Encryption Requirement | Example Data Types |

| Confidential (High) | Catastrophic | Mandatory DAR + DIT (E2EE/Client, Side) | Financial Records, Intellectual Property, Authentication Data |

| Internal Use Only (Medium) | Non, Catastrophic | Mandatory DAR, Strong TLS/DIT (Situational E2EE) | Non, confidential emails, Internal reports |

| Public (Low) | Minimal | Baseline HTTPS/TLS for transmission | Public website content |

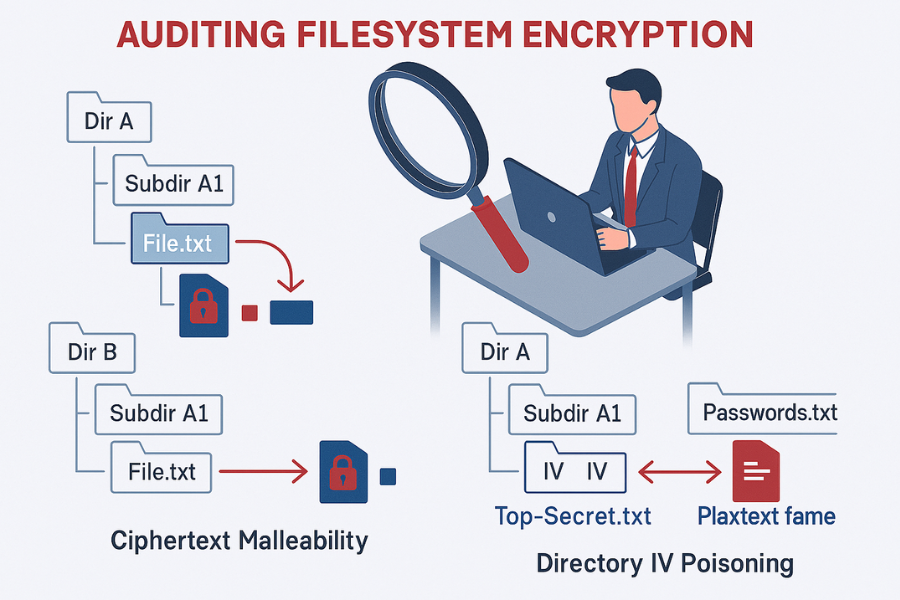

1.2. The Three States of Data that Demand Encryption

Effective data management requires governance across the six stages of the data life cycle: collection, storage, processing, sharing, analysis, and retirement. Encryption protocols must cover the three distinct states of data within this cycle.

Data At Rest (DAR)

This state covers data stored statically on physical media, including hard disks, solid, state drives, tapes, and archived backups. Encryption at rest is achieved via Whole Disk Encryption (WDE) or file, level container encryption.

Data In Transit (DIT)

Data is in transit when it is transferred between components, applications, or network locations. Protection in this state requires securing the communication channel using protocols like TLS (Transport Layer Security) for websites and emails, or VPNs.

Data In Use (CI , Confidentiality in Use)

This is the state where data is actively being processed in memory (RAM) or by the CPU. Protecting data in this specialized state requires highly advanced controls. Some modern computing environments, such as specialized AMD and Intel chipset, based Confidential Compute VMs, keep the data encrypted in memory by using hardware, managed keys during processing.

The Hidden Risk of Mobile Devices

NIST guidance, specifically SP 800-171, indicates that Data At Rest (DAR) encryption is not strictly required for servers or desktops located within a facility’s secure boundary, as other security controls are presumed to be in place. However, the same standard clearly mandates that Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI) on mobile devices must be encrypted.

This distinction creates a dangerous operational grey area. Since most modern employees use laptops that routinely leave the secure facility, relying on the internal network boundary exemption is irresponsible. Deploying DAR encryption, such as BitLocker or FileVault, across all endpoint devices is considered “cheap and easy insurance” to prevent data loss if a device is physically lost or stolen. Therefore, for virtually all corporate environments, whole disk encryption functions as a de facto requirement to secure data consistently.

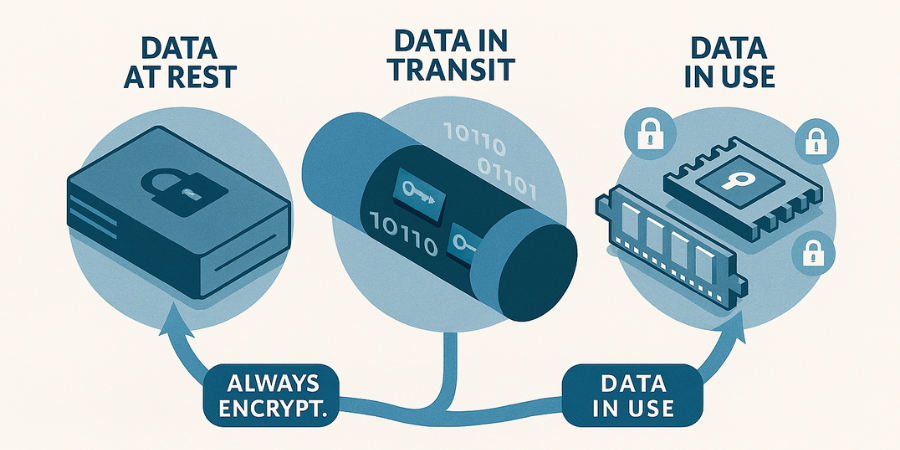

2. Encrypting Data At Rest (Drives and Local Files)

Whole Disk Encryption (WDE) is the foundational layer of protection against unauthorized access resulting from physical theft. Microsoft BitLocker is the standard tool for Windows systems, relying heavily on the Trusted Platform Module (TPM) for key security.

2.1. BitLocker Drive Encryption (Windows Standard)

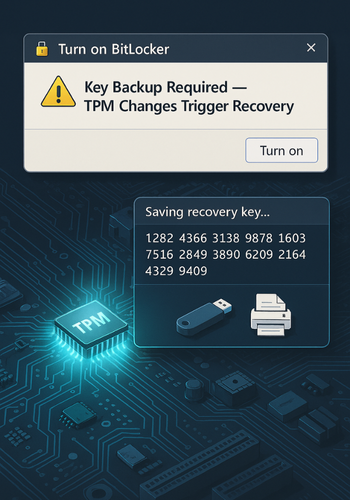

The prerequisite for smooth BitLocker operation is ensuring the device’s TPM is correctly configured. Before initiating the encryption process, a technician must confirm that the TPM is activated within the BIOS settings, typically found under the Security or TPM Security menu.

Critical Safety Step: Suspending Protection

BitLocker uses Platform Configuration Register (PCR) values stored in the TPM to verify the integrity of the boot environment. Any change to hardware, firmware, or BIOS settings can change these values, triggering the BitLocker recovery screen. It is mandatory to suspend BitLocker protection temporarily before applying any UEFI, BIOS, or TPM firmware updates to prevent the system from entering recovery mode unnecessarily.

Steps: Enabling BitLocker and Key Backup

The process of enabling BitLocker is straightforward, but the subsequent key management step is the most critical to security and long, term data access.

- Start Encryption: Access the BitLocker Drive Encryption settings, usually found in the Control Panel under System and Security. Select the drive to encrypt (often the C: drive) and choose “Turn on BitLocker.”

- Choose Key Backup Method: The 48, digit recovery key is the only method to regain access if the TPM fails or the hardware configuration changes. This key must be saved redundantly and securely.

- Offline USB Storage: Choose “Save to a USB flash drive.” This creates a backup completely protected from network, based attacks.

- Text File/Network Location: The “Save to file” option allows storage in a secure network location or another encrypted drive.

- Physical Print: Choosing “Print the recovery key” and storing the paper copy in a secure, offsite location, such as a bank safety deposit box, provides a crucial physical barrier against digital failure or breach.

- Managed Environments: For corporate devices, verification must be made to ensure the key is stored successfully in Microsoft Entra ID or Active Directory Domain Services (AD DS) before the encryption process is finalized.

- Choose Encryption Scope: The user selects whether to encrypt the entire drive or just the used disk space. Encrypting the entire drive is safer for devices that may later store highly sensitive files.

- Verification: After the process completes, the drive icon in the file explorer should display a lock symbol, confirming protection.

2.2. File Container Encryption

For systems running Windows Home, which lacks BitLocker, or for cross, operating system file sharing, container, based encryption using tools like 7, Zip provides robust, file, level protection.

When creating an encrypted archive, the security of the operation depends on the chosen algorithm and settings. It is critical to select AES-256 encryption (the gold standard) and, crucially, to check the option to “Encrypt file names” within the utility’s settings. If file names remain unencrypted, an attacker who gains access to the archive structure can still glean context about the contents, such as the titles of sensitive documents, even if they cannot read the files themselves.

The Hidden Cost of WDE Key Failure

The process of key backup is not merely a formality, it is the ultimate data preservation mechanism. If a user loses the 48, digit recovery key and the system is triggered into recovery mode due to an unexpected event, such as a faulty firmware update, the only available recourse besides entering the key is complete Operating System reinstallation. This highlights that key management, the secure storage and retrieval of the recovery key, is practically more important than the strength of the encryption algorithm itself.

3. Protecting Data In Transit (Email and Communication)

Data sent across the internet requires protection against unauthorized disclosure. The required level of protection depends on whether the data needs to be secured only during transport or also after it arrives at the destination.

3.1. TLS vs. End, to, End Encryption (E2EE): The Fundamental Difference

When data is sent, it is either protected by Transport Layer Security (TLS) or End, to, End Encryption (E2EE).

- TLS (Transport Layer Security): This protocol secures the connection during transmission. It is indicated by the lock icon next to a website URL. While TLS prevents interception (man, in, the, middle attacks), the email provider (e.g., Google or Microsoft) still holds the keys and can view the plaintext data when it rests on their servers.

- E2EE (End, to, End Encryption): This method ensures that the data is encrypted on the sender’s device and can only be decrypted by the recipient’s device. E2EE protects the data both in transit and at rest on the recipient’s storage or mail client. For sensitive data, E2EE provides the highest degree of confidentiality and access control, as the data never sits unsecured in the mail server environment.

3.2. Email E2EE Methods: PGP vs. S/MIME

For email, two widely adopted standards provide encryption and digital signatures: Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) and Secure/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (S/MIME). They differ significantly in how keys are managed and verified.

PGP relies on a Web of Trust model, where users manually validate the authenticity of keys belonging to their contacts. This decentralized approach is often favored by journalists and privacy advocates who wish to avoid relying on a central authority.

S/MIME, conversely, relies on a hierarchical Public Key Infrastructure (PKI), where trust is granted by central Certificate Authorities (CAs). While more expensive due to the reliance on paid certificates, S/MIME is generally more efficient and convenient in large industrial or corporate environments where central management and automated transformation of applications are priorities.

PGP vs. S/MIME Comparison

| Feature | PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) | S/MIME (Secure/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions) |

| Primary Use Case | Personal privacy, Journalism, Decentralized exchange | Corporate, Enterprise, Large Organizations |

| Trust Model | Web of Trust (User validates keys manually) | Hierarchical PKI (Relies on central Certificate Authority) |

| Setup Convenience | Less convenient due to manual setup and key management | More convenient, automated integration via corporate PKI |

| Cost | Less expensive (GnuPG is free and open, source) | More expensive, reliance on paid certificates/infrastructure |

3.3. Tutorial: Generating and Sharing a PGP Key Pair (GnuPG)

GnuPG (GPG) is the open, source implementation of PGP. Secure communication begins with the creation and safe management of a key pair, a private key kept secret for decryption, and a public key shared widely for others to encrypt data for the user.

Prerequisites

The user must install the GPG command line tools for their operating system (e.g., sudo apt-get install gnupg on Linux or via a distribution from gnupg.org for Windows/macOS).

Steps: PGP Key Generation (GPG Command Line)

- Generate Full Key: Execute the command

gpg --full-gen-key. - Specify Key Type: Follow the prompts to select the key kind and algorithm. Modern security best practice suggests creating a strong, primary key for certification/signing and separate sub, keys for encryption.

- Specify Key Size and Expiry: Use a minimum key size of 4096 bits and set a realistic expiration length (e.g., 1 year).

- Enter User Information: Input the user ID information, typically including a name and email address.

- Set Passphrase: Set a highly secure, complex passphrase. This phrase protects the private key file.

- List Keys: To retrieve the Key ID needed for sharing, use

gpg --list-secret-keys --keyid-format=long.

Share it Safely (Public Key Exchange)

The public key is exported so correspondents can encrypt messages. The key must be exported in ASCII armor format for easy transmission via email or website.

- Export Public Key (ASCII Armor): Use the Key ID (e.g.,

3AA5C34371567BD2) in the export command.- Command:

gpg --armor --export 3AA5C34371567BD2

- Command:

- Distribution: Copy the entire output text, which begins with

-----BEGIN PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK-----, and share it with contacts or upload it to a public key server (e.g., key.openpgp.org).

Proof of Work: Verifying a Signature

Verifying a digital signature confirms two things: the file has not been altered since it was signed, and the sender is genuinely the owner of the private key.

- Acquire Files: The user must have the original document (e.g.,

document.pdf), the corresponding detached signature file (e.g.,document.pdf.sig), and the sender’s public key imported into their GPG keyring. - Verify: Run the verification command:

- Command:

gpg --verify document.pdf.sig document.pdf

- Command:

- Outcome: A successful verification confirms a “Good signature” from the specified user ID.

3.4. Instant Messaging Gold Standard

While PGP is vital for formal email exchange, for high, security, real, time communication, dedicated messaging platforms using the Signal Protocol are the modern preference.

The Signal Protocol integrates advanced cryptographic principles like the Double Ratchet Algorithm, 3, DH handshake, and strong primitives (AES-256, HMAC-SHA256). This protocol provides automatic key management and forward secrecy, solving the high user friction and complex key exchange inherent in manual PGP email. The Signal Protocol is considered the gold standard against which other messaging security protocols are judged.

4. Securely Encrypting Backups and Cloud Storage

Sensitive data must be encrypted before it is stored or backed up in a location where a third party might have physical or administrative access. Encryption applies to data both in transit to the backup location and at rest once it is stored.

4.1. The Cloud Encryption Showdown: Server, Side vs. Client, Side

Cloud providers typically offer Server, Side Encryption (SSE), where data is encrypted after it reaches the provider’s server. While this offers protection against external data center theft, it fails to protect against unauthorized access by the provider itself or compromised service administrators.

Client, Side Encryption (CSE) addresses this by securing the data on the user’s device before it ever leaves their control. This ensures that the sensitive information remains under the user’s direct authority.

Server, Side vs. Client, Side Encryption

| Factor | Server, Side Encryption (SSE) | Client, Side Encryption (CSE) |

| Key Control | Service Provider manages keys | User retains absolute, full control over keys |

| Data Visibility | Provider can decrypt if required | Provider only sees ciphertext, cannot decrypt data |

| Insider Risk | High, Admins with full S3 access can decrypt data easily | Minimal, Data is secured at the source device |

| Protection Point | Encrypted only once it reaches the cloud server | Encrypted before leaving the local device |

SSE Limitations and Key Control

Starting in 2023, Amazon S3 began applying Server, Side Encryption with S3 managed keys (SSE-S3) as the default base level of encryption for all new object uploads. This is a positive development for baseline security.

However, relying solely on SSE is often inadequate for highly regulated or sensitive data. A critical limitation of basic SSE-S3 is the absence of role separation and key rotation capabilities. An administrator who possesses full access to the S3 infrastructure often retains the ability to decrypt the data easily. Furthermore, the master key and the respective data keys are fully managed by the provider, giving the users no control over the core cryptographic security. For environments requiring data sovereignty and strict compliance (such as GDPR or HIPAA), CSE is mandatory because it ensures the encryption key never leaves the client device.

4.2. Tutorial: Implementing Client, Side Encryption with Cryptomator

Cryptomator is a popular open, source tool that allows users to create encrypted vaults directly within their existing cloud storage folders (e.g., Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive, WebDAV, or S3). It encrypts files and filenames using AES-256 and utilizes the strong scrypt key derivation function to protect the password.

Steps: Creating a Cryptomator Vault

- Install and Locate Cloud Folder: Install the Cryptomator application and identify the local synchronization folder for the chosen cloud service.

- Create a Vault: Select the cloud folder location and assign a strong vault password. Cryptomator handles the generation of complex cryptographic keys automatically based on this password.

- Gotcha: The vault password is the sole access mechanism, deriving the master key. Losing this password renders the data permanently inaccessible.

- Unlock and Mount: Enter the password to unlock the vault. Cryptomator immediately provides a virtual encrypted drive that appears like a standard mounted disk.

- Store Data: Move or save files to this virtual drive. The application performs client, side encryption instantly before the cloud synchronization software uploads the file.

- Verification: When viewing the files directly within the cloud provider’s interface or the local cloud folder, all content will be scrambled, including the file names and folder structure.

5. The Single Point of Failure: Key Management and Recovery

The most robust encryption algorithm is useless if the key is compromised or lost. The entire security model rests on the principle of key secrecy.

5.1. The Fundamental Rule: Key Secrecy and Management

NIST guidance emphasizes that if a strong cryptographic key is generated but is not kept secret, the protected data is exposed. Organizations must adopt robust key management practices across three core areas:

- Secure Storage (Retrieval): Keys must be protected from unauthorized access using hardware security modules (HSMs) or encrypted databases. Strict access controls should govern who can retrieve or manage the key material.

- Redundancy: Backup keys must be stored securely and physically separate from the primary storage to prevent a single point of failure from wiping out access.

- Rotation: Keys should be rotated regularly, annually or immediately after a security event, such as a staff member departing, to limit the potential damage caused by a discovered or leaked key.

5.2. Technical Deep Dive: Key Derivation Functions (KDFs)

A Key Derivation Function takes a human, memorable password and stretches it, making it extremely difficult to reverse, engineer into a usable encryption key. This stretching process must be deliberately computationally intensive to deter brute, force guessing attacks.

Scrypt vs. PBKDF2

Cryptomator, along with many modern applications, uses Scrypt. Scrypt is significantly stronger than older functions like PBKDF2. PBKDF2 relies primarily on computational time (iteration count) to slow down cracking attempts. Attackers can mitigate this slowness by using massive parallelism across hundreds of specialized devices like GPUs or ASICs, as PBKDF2 has minimal memory requirements per thread.

Scrypt, however, is a memory, hard function. It is designed to require a large and adjustable amount of memory to compute efficiently. This memory requirement makes it vastly more expensive and difficult for attackers to parallelize brute, force operations, drastically shifting the economic viability in favor of the defender. For instance, on modern hardware, the cost of a hardware brute, force attack against Scrypt is estimated to be orders of magnitude greater than a similar attack against PBKDF2. This is an essential defense layer for any password, protected encryption container stored offline or in the cloud.

5.3. Troubleshooting Key Rotation Failures

In enterprise environments, key rotation failures can disrupt operations and cause potential data loss, especially when dealing with databases or complex backup systems.

| Symptom / Context | Root Cause | Fix |

SQL Server BACKUP LOG fails after TDE key rotation (Cannot find server certificate with thumbprint '%') |

The original encryption certificate was dropped or became inaccessible before the backup completed, breaking the cryptographic chain. | Restore the previous certification (if a backup exists) and retry the backup operation. Maintaining certification backups is highly recommended. |

Veritas NetBackup rotation failed (Private Key Encryption State: Encrypted with an unknown passphrase) |

The passphrase file or key file was tampered with or corrupted, indicating a possible internal data integrity issue. | Clean up the keystore folder, including hidden files, and retry the rotation operation. If the issue persists, restoration of the passphrase file and corresponding private key files is necessary. |

| Cannot decrypt backup data (e.g., cloud backup) | The encryption key is lost, missing, or the database record holding the key phrase is corrupted. | Search meticulously through local or legacy backups of the database for the original key phrase or text string used for encryption. |

6. Troubleshooting Whole Disk and Backup Encryption

Encryption systems are deliberately designed to fail safe, meaning they fail by rendering the data inaccessible rather than by exposing it. This makes troubleshooting key loss a high, stakes scenario.

Troubleshoot Table: BitLocker and TPM Errors

| Symptom / Exact Error | Root Cause | Non, Destructive Test/Fix | Last, Resort Fix (Data Loss Warning) |

| BitLocker Recovery screen appears unexpectedly after system startup | TPM detected changes to hardware or boot configuration (e.g., BIOS/UEFI update, component replacement). | Enter the 48, digit recovery key (stored securely on USB or paper). | DATA LOSS RISK: If the key is lost, the only resolution may be OS reinstallation and wiping the encrypted drive. |

| TPM failing to initialize or prepare for BitLocker | TPM state lock, out, module state mismatch, or temporary lock due to multiple authentication failures. | Access UEFI/BIOS, disable the TPM, boot to Windows, then reboot and re, enable the TPM in UEFI/BIOS, and retry starting BitLocker. | Clear the TPM via the Windows Management Console (Run TPM.MSC and select Clear TPM) or using the elevated PowerShell script provided by Microsoft. |

| Cannot access cloud backup files, decryption fails | Encryption key for the backup vault is permanently lost or forgotten. | If possible, search local systems or previous database copies for the key string. | IRREVERSIBLE DATA LOSS. If the key is truly lost, cryptographic design ensures the data is permanently unrecoverable by any means. |

Final Warning on Key Loss

It is a core tenet of modern cryptography that there is no backdoor. If an encryption key (such as a BitLocker recovery key or a Cryptomator vault password) is truly lost, the data is permanently inaccessible. No manufacturer, support team, or law enforcement agency can retrieve the data. Data integrity relies entirely on the successful execution of key management procedures.

7. Conclusion and Comprehensive FAQ

Encryption is not merely a technical step, it is a layered, continuous security posture driven by strict organizational policies regarding data classification. By adopting strong Whole Disk Encryption, moving to Client, Side Encryption for cloud assets, and maintaining a rigorous protocol for key storage, rotation, and recovery, organizations ensure data sovereignty and achieve compliance across the entire digital landscape. The frequency of encryption is fixed: it must be applied continuously to sensitive data throughout its life cycle.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Does encryption significantly slow my computer down

Modern symmetric algorithms like AES-256 are highly optimized, often utilizing hardware acceleration (AES-NI). For Whole Disk Encryption, the typical performance loss is minimal, often less than 5%, unless the system is subjected to extremely heavy loads, such as large database operations.

2. Is default cloud encryption (like Amazon S3 SSE-S3) good enough

SSE-S3 provides baseline protection for data at rest, but it is insufficient for sensitive or regulated data because the cloud provider retains control over the encryption keys. For compliance (GDPR, HIPAA) or maximal privacy, Client, Side Encryption (CSE) is strongly required.

3. What is the minimum key length required today

The modern standard is the use of AES-256. While a minimum length of 128 bits is acceptable, AES-256 is recommended. Older standards like DES (56 bits) are considered obsolete and vulnerable to brute, force attacks.

4. Why did my BitLocker key suddenly stop working

The key itself is stable, but the system likely entered recovery mode because the Trusted Platform Module (TPM) detected an unauthorized change to the system’s boot configuration, often caused by a firmware or BIOS update. Entering the 48, digit recovery key is necessary to unlock the drive.

5. What is the difference between AES-256 and PGP encryption

AES-256 is a symmetric block cipher, which uses a single key for fast encryption and decryption of large data sets. PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) is an application protocol that combines symmetric encryption (often AES) with asymmetric encryption (RSA/ECC) for key exchange and digital signatures.

6. If E2EE messaging (like Signal) is used, is email encryption still necessary

Yes. While E2EE messaging uses superior, automatically managed key protocols, email encryption (PGP/S/MIME) is necessary when communicating with external partners who do not use the same platform, or for formal exchange of documents that require digital signatures and non, ephemeral communication records.

7. Can a lost Cryptomator password be recovered

No. Cryptomator uses the password to derive the master encryption key using the Scrypt function. If the password is forgotten, the data is rendered permanently inaccessible due to the cryptographic design.

8. Why do experts prefer Scrypt over PBKDF2 for password hashing

Scrypt is a memory, hard key derivation function. Unlike PBKDF2, which is vulnerable to cheap, parallel GPU attacks, Scrypt requires significant memory resources, making brute, forcing passwords exponentially more difficult and expensive for attackers using specialized hardware.

9. Should public data or low, sensitivity files be encrypted

Encrypting the data content itself is typically unnecessary. However, the transmission channels used to move the data should still employ TLS/HTTPS to ensure data integrity and prevent tampering.

10. What is “data in use” encryption

“Data in use” describes data actively being processed in memory or by the CPU. Protection in this state requires specialized hardware solutions, such as Confidential Compute VMs, which maintain the data in an encrypted state even while it is being computed.

11. How often should I rotate my encryption keys

Key rotation frequency should be policy, driven. Key rotation is mandatory upon staff departure or system compromise, and generally recommended annually for critical infrastructure and master backup keys to limit the damage from potential leakage.

12. What specific compliance rules mandate encryption

Regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI, DSS) all require robust encryption for sensitive data both at rest and in transit.

13. Is the Triple Data Encryption Standard (3DES) still considered secure

Triple DES (3DES) is generally considered obsolete today due to its smaller block size and susceptibility to attacks. Modern security practices dictate transitioning to AES-256 for all new deployments.

14. How should a public GPG key be shared safely

The recommended method is to export the key using ASCII armor (gpg –armor –export) and upload it to a trusted public key server (key.openpgp.org). The key fingerprint should also be published on separate, verified channels for recipients to validate its authenticity.

15. What are the risks of storing encryption keys in the cloud

If the service provider manages the keys (even through SSE-KMS), there is an inherent risk that the provider’s staff or a sophisticated attacker who compromises the central infrastructure could gain access to the keys. Client, Side Encryption is the only way to fully mitigate this control risk.

Conclusion

Encryption is not merely a technical step, it is a layered, continuous security posture driven by strict organizational policies regarding data classification. By adopting strong Whole Disk Encryption, moving to Client, Side Encryption for cloud assets, and maintaining a rigorous protocol for key storage, rotation, and recovery, organizations ensure data sovereignty and achieve compliance across the entire digital landscape. The frequency of encryption is fixed: it must be applied continuously to sensitive data throughout its life cycle.