Managing Encrypted Vaults: Advanced Workflow for Folder Lock and Cloud Sync

This expert guide, developed by Newsoftwares.net, provides the definitive solution for managing Folder Lock encrypted files within cloud sync environments. If your encrypted files are causing perpetual sync errors, file duplication, or persistent “file locked” notifications, the immediate solution is simple: Stop syncing files that are actively encrypted, hidden, or opened by Folder Lock. The only successful workflow demands treating the encrypted Locker container as a single, opaque data block. You must ensure the Locker is fully closed before the cloud service (OneDrive, Dropbox, Google Drive) attempts to sync it. This workflow guarantees both reliable synchronization and robust, portable AES-256 encryption.

1. The Immediate Fix: How to Stop Encrypted File Conflicts Today

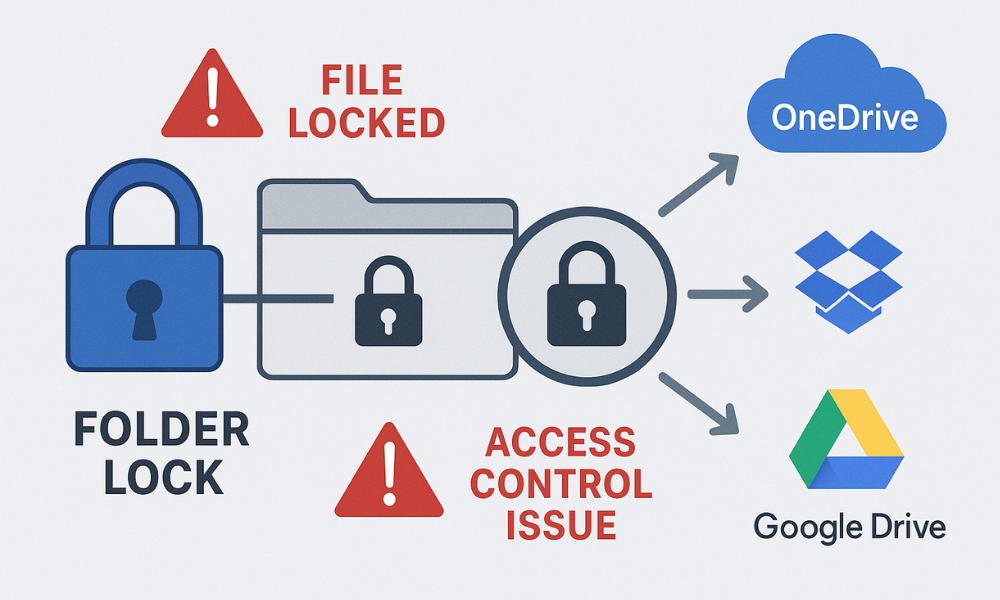

The most common source of conflict arises from a fundamental incompatibility: the granular, kernel, level file locking used by client, side security tools versus the continuous monitoring required by cloud sync engines. Cloud sync clients constantly monitor directories for file changes, relying on specific file system permissions to operate. When a user applies Folder Lock’s simple file locking feature, often chosen for quick file concealment, it implements a “hard lock” by using a kernel, level driver to restrict access and set strong system permissions (NTFS or HFS Plus). This deep, level access block directly clashes with the cloud service’s attempt to read, hash, and upload the file, resulting in continuous “File locked” or “Access Control Issues” errors.

To maintain both security and synchronization reliability, professionals must adhere to a strict workflow that isolates the encryption process from the sync process.

1.1 The Workflow Shift: Why Simple File Locking Fails in the Cloud

Simple file locking is effective for hiding files on a local desktop but is catastrophic in a shared cloud environment. The reliable solution requires a strategic shift to Folder Lock’s more robust encryption feature.

The essential outcomes for a secure and functional environment are threefold:

- Outcome 1: Embrace the Locker Container. The only feature of Folder Lock suitable for cloud synchronization is the creation of a virtual Locker file. This single, monolithic file (often with a proprietary extension like

.fld) is secured using AES-256 encryption. - Outcome 2: Sync the Closed Block. The sealed, single Locker file must be placed inside the cloud sync folder (OneDrive, Dropbox, or Google Drive). Crucially, this Locker file must never be opened or modified while it resides in the actively monitored directory.

- Outcome 3: Optimize with Selective Sync. For efficiency, especially with large vaults, utilize the cloud service’s selective sync features to keep the sealed Locker file marked as “Online, Only.” This saves valuable local disk space and requires the full download only when the file must be accessed.

1.2 Defining the Core Problem: Conflict, Corruption, and Version Creep

Sync failures manifest in three specific ways, depending on the error in the workflow.

Conflict

Conflict errors, indicated by persistent status messages like “Processing changes” or the exact error string “Dropbox the file cannot be accessed by the system”, are caused by the security application maintaining an open or locked state on the file. If a user attempts to lock individual files instead of using the encrypted container, the cloud client registers an immediate access violation because it cannot resolve the file system permissions enforced by the security software’s kernel driver.

Corruption

Data corruption is a severe risk resulting from synchronizing files that are only partially encrypted or decrypted. If a third, party tool’s encryption (or Folder Lock’s on, the, fly decryption mechanism) is interrupted mid, process when the sync service attempts to upload, the resulting file in the cloud may be incomplete or unreadable. For example, if a file uploaded to the cloud is marked with an encryption header like __CLOUDSYNC_ENC__ but cannot be decrypted by the tool, it is likely corrupted. The only reliable prevention is ensuring that only the fully sealed, monolithic Locker file is ever introduced to the synchronization path.

Version Creep

Version creep occurs because the cloud service views the Locker file as a single, atomic binary block. If a user opens a 20 GB Locker, makes a minor change to a 5 KB spreadsheet inside it, and then closes the Locker, the cloud service detects a change across the entire 20 GB file. Consequently, the service uploads the entire 20 GB file as a new version history entry, rapidly consuming bandwidth, cloud storage quota, and making granular recovery extremely tedious, as recovering a single file requires downloading the entire historical vault.

2. Deep Dive: The Folder Lock Mechanism

Security, conscious professionals must understand the technical architecture underlying the Folder Lock mechanism, particularly the cryptographic strength and the efficiency trade, offs.

2.1 Locker Anatomy: Understanding the AES-256 Virtual Drive

The core security component offered by Folder Lock is the Encrypted Locker, which functions as a dynamically expanding virtual drive.

Encryption Standard

The integrity of the data at rest is guaranteed by the use of AES-256 (Advanced Encryption Standard). This algorithm is recognized internationally as military, grade and is the accepted standard for the secure protection of classified information. The encryption is applied on, the, fly, meaning files are immediately encoded as they are written into the virtual drive.

Dynamic Size and Zero Trace Decryption

Unlike older, less flexible container methods, the Folder Lock Locker uses a dynamic storage system that automatically expands as the user adds more data, preventing the pre, allocation of fixed disk space.

Furthermore, the decryption process is engineered for maximum security through Zero Trace Decryption. When a user successfully opens and mounts the Locker, the decryption process occurs automatically in memory (RAM). Crucially, the unencrypted plaintext version of the files only resides temporarily in the computer’s volatile memory. Once the user closes the Locker, the virtual drive is dismounted, and the unencrypted data is erased from memory, ensuring that no plain text remains exposed on the persistent hard drive.

2.2 Security Insight: Key Strength and KDF Resistance

The unassailable strength of AES-256 relies entirely on the quality of the derived encryption key. This key, in turn, is dependent on the user’s master password and the Key Derivation Function (KDF) that processes it.

The architecture utilizes AES 256, bit for primary data encryption. For sharing and managing user profiles, the platform also implements RSA encryption, sometimes cited at 128, bit or 4096, bit variants. The RSA component is what permits secure collaboration, allowing different authorized individuals to open the same encrypted container using their own unique credentials, as the key needed to decrypt the data is distinct from the individual login password.

Key Derivation for Brute, Force Defense

KDFs (Key Derivation Functions) are fundamental to protecting the master password hash from brute, force and dictionary attacks. If the password were hashed without strengthening, an attacker could quickly test millions of common passwords. KDFs, which include memory, hard functions like Argon2 or iterative hashing like PBKDF2/AES-KDF, deliberately introduce computational effort, requiring the attacker to spend substantial time and resources for every single guess, a process called key stretching.

Since specific details about Folder Lock’s KDF iteration counts are not always public, the user must compensate for any proprietary or suboptimal implementation by maximizing password strength. NIST recommends KDF iteration counts starting at 10,000, but critical keys may require millions of iterations to resist powerful systems. The necessity of using a master password of exceptionally high entropy (long and complex) cannot be overstated, as this mitigates the risk of dictionary attacks, irrespective of the KDF function’s internal settings.

2.3 Proof of Work: Encryption Speed vs. Disk Performance Impact

Real, time encryption is not free, it imposes a measurable performance cost during input/output (I/O) operations. The impact is significant during bulk file transfers, although negligible during typical file access, thanks to hardware acceleration (AES-NI).

Encryption Performance Impact Analysis

| Operation Type | Performance Characteristic | Observed Performance Loss | Implication for Folder Lock | Source |

| Sequential Write Speed | Involves encrypting data before committing to disk. | 50% , 62% loss (on HDDs/SSDs) | Writing large files into a mounted Locker is the primary bottleneck. | |

| Sequential Read Speed | Involves decrypting data as it is read from disk. | Less than 5% loss | Opening and reading files from a mounted Locker is fast due to dedicated processor instructions. | |

| Random IOPS (General) | High volume, non, sequential operations. | Noticeable reduction in raw Input/Output Operations Per Second. | Performance dip is a necessary security trade, off for real, time encryption. |

The technical data indicates that write operations, such as saving a complex file or migrating a large folder set into the secure container, experience the highest performance penalty due to the mandatory cryptographic step before data persistence. For desktop environments, this is the expected cost of using strong, on, the, fly data protection.

3. Secure Synchronization Workflow

Establishing a reliable sync requires meticulous separation of the encryption environment from the cloud environment.

3.1 Prerequisites and Initial Configuration

- Segregate Sync Paths: The staging location used for creating and opening the Locker must be explicitly located outside the main cloud sync folder hierarchy (e.g.,

C:\LocalStaging, rather thanC:\Users\User\Dropbox\). This isolation prevents the cloud client from attempting to sync the Locker while it is open and being actively modified. - Backup Master Key: Securely record the Folder Lock master password and any corresponding serial number (which can act as a recovery key for registered users). Store this high, entropy data in a dedicated, offline password manager, such as a KeePass database, which itself utilizes strong KDFs like Argon2 to ensure the password hash is attack, resistant.

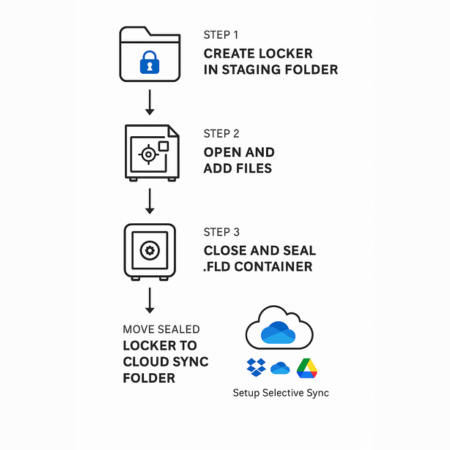

3.2 Tutorial 1: Creating and Sealing the Cloud Locker

This process creates the secure container locally, ensures its integrity, and introduces the final, sealed file to the cloud.

Step 1: Create the Locker Locally

- Action: Launch the Folder Lock software.

- Action: Select the “Encrypt Files” option to initiate container creation.

- Action: Define a strong master password, ensuring it exceeds 16 characters for maximum protection against key guessing attacks.

- Gotcha: Confirm that the Locker creation path is set to the designated segregated staging location.

Step 2: Migrate Sensitive Data

- Action: Open the new Locker. It will mount as a virtual drive letter or folder within the operating system.

- Action: Drag and drop all sensitive files into this mounted virtual drive.

- Verification: Briefly access a file inside the mounted drive to confirm the data migration was successful and the file structure is intact.

Step 3: Close the Locker and Move the Container File

- Action: This is the most crucial step. Use the Folder Lock interface to explicitly close the Locker. This action dismounts the virtual drive and commits all encrypted changes into the single, sealed

.fldcontainer file. - Action: Move this sealed

.fldfile from the staging area into the cloud sync folder (e.g.,C:\Users\User\Google Drive\EncryptedVaults\).

Step 4: Verify Sync and Lock Status

- Action: Monitor the cloud service icon in the system tray. The service should detect and upload only the single, large

.fldfile. - Verification: Once the upload finishes, verify the status icon on the file shows successful completion (e.g., a green checkmark), confirming the service recognizes the container as a static, synchronized object, and not a continuously changing file.

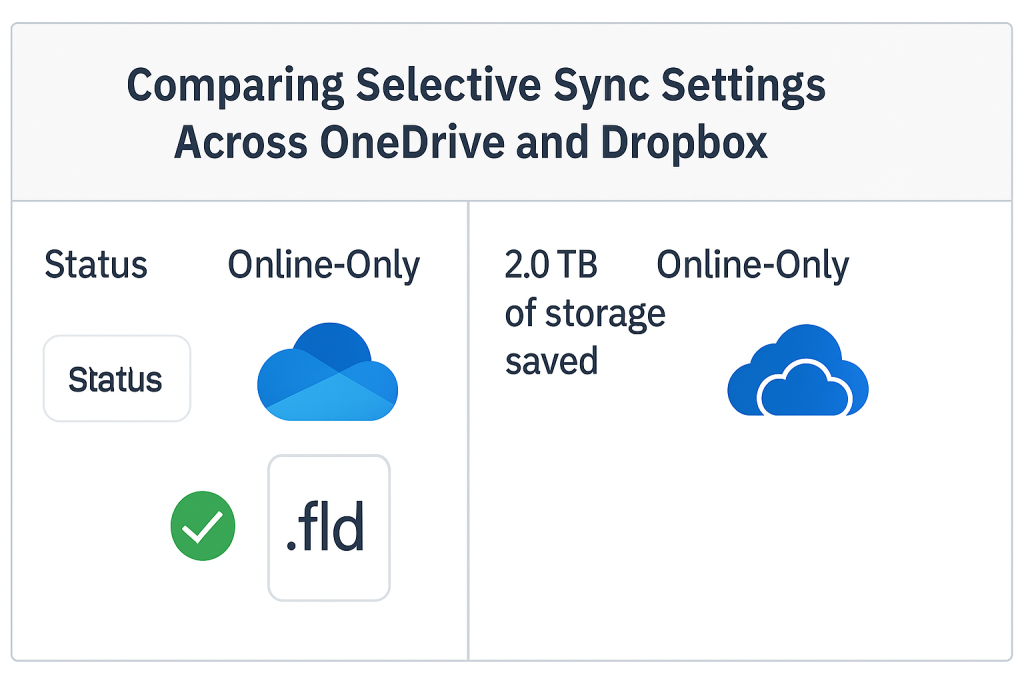

3.3 Tutorial 2: Selective Sync Optimization for Space and Speed

For large Locker files, selective synchronization is mandatory to prevent unnecessary local storage consumption.

Step, by, Step for OneDrive (Windows)

- Action: Ensure the OneDrive desktop application is running.

- Action: Navigate to the Locker file location in File Explorer.

- Action: Right, click the

.fldfile and select “Free up space.” - Outcome: OneDrive purges the local data copy, changing the file status to “Online, only” (indicated by a cloud icon), occupying zero local space.

- Gotcha: To open the Locker, you must first download it. Right, click the file and select “Always keep on this device” or double, click to force the download before launching Folder Lock.

Step, by, Step for Dropbox (Windows/Mac)

- Action: Open the Dropbox desktop application settings (Preferences).

- Action: Navigate to the Sync tab and select the Selective Sync option.

- Action: Deselect the checkbox next to the specific folder containing the large Locker file.

- Outcome: Dropbox removes the local copy of the folder and its contents, leaving the data safely secured in the cloud.

- Alternative: Use Dropbox Smart Sync by right, clicking the file in Explorer/Finder and marking it as “Online, only” for more granular control.

4. Managing Access, Versioning, and Portability

The monolithic nature of the encrypted Locker changes how version control and data sharing function within cloud ecosystems.

4.1 Version History Dynamics in Cloud Storage

Because the cloud sync engine cannot inspect the contents of the binary Locker file, every edit made inside the mounted Locker is registered as a complete modification of the single, large container file.

If a 50 GB Locker is opened, a single 10 KB file is edited, and the Locker is closed, the cloud service saves the entire 50 GB file as a new version history entry. This rapid accumulation of large historical versions quickly exhausts cloud storage quotas and complicates recovery. Retrieving an older version of a single internal document requires the user to manually download the entire 50 GB historical Locker file, open it, and then extract the desired document, sacrificing granular recovery for comprehensive encryption.

4.2 Secure Sharing and Selective Unlock

Folder Lock’s design, incorporating RSA encryption for user profiles, enables secure file sharing that enhances collaboration without relying on a single password.

The shared access framework utilizes public and private keys, decoupling the data’s encryption key from the individual user’s login password. This separation allows the Locker creator to securely share the .fld file via the cloud service. Collaborators, after downloading the file, can use their own unique credentials (assigned by the creator) to open the vault. Access rights are often managed within the Locker settings, ensuring authorized users only interact with content based on their defined permissions.

Recommended Secure Key Exchange Practice

The master password or specific profile key used to access the Locker must never travel through the same cloud channel as the encrypted data file itself.

- Action: Share the encrypted

.fldfile link through OneDrive, Dropbox, or Google Drive. - Action: Transmit the required access key or password using an entirely separate, secure communication platform that features end, to, end encryption and ephemeral messaging (e.g., Signal, or a link set to expire within 24 hours).

4.3 Cross, Platform Portability (iOS/Android)

Folder Lock supports synchronization across desktop and mobile operating systems, allowing the user to access encrypted data via dedicated iOS and Android applications.

The mobile application integrates directly with cloud providers (Dropbox, OneDrive, Google Drive) for backup and retrieval. Once the Locker file is downloaded by the mobile app, the user enters the password, and the content is decrypted for mobile viewing.

A critical caveat in mobile security is the strict sandboxing enforced by operating systems. To ensure proper encryption, sensitive files originating on the device (e.g., photos or videos) must be explicitly imported or created within the Folder Lock app interface. Files left in the mobile OS’s native photo gallery or document folder typically remain outside the Locker’s cryptographic protection, despite the presence of the application.

5. Troubleshooting and Conflict Resolution Matrix

When sync fails, the issue is almost universally related to access control conflicts between the security application’s kernel driver and the cloud client’s file access APIs. Troubleshooting focuses on ensuring the Folder Lock process releases the file handle before sync resumes.

5.1 Root Cause Analysis: Why Sync Engines Fight Encryption Drivers

Cloud sync applications rely on system, level APIs to enforce file status (read, write, online, only). Security software that employs kernel, level blocking mechanisms, designed to hide files or prevent access, disrupts these expected API calls. This results in the cloud service generating specific access errors because it cannot obtain the necessary permissions to hash or upload the file. Resolution hinges on ensuring the Locker is sealed and that no residual Folder Lock processes are active while the cloud client is running.

5.2 The Critical Fix Matrix: Symptoms, Causes, and Immediate Actions

This matrix provides targeted solutions for the most common sync failure scenarios.

Troubleshooting Encrypted Cloud Sync Failures

| Symptom / Error Message (Exact Strings) | Root Cause | Non, Destructive Test | Fix / Last, Resort Option |

| OneDrive “File locked” icon or “Processing changes” continually | Locker contents are open, or a background Folder Lock process is still holding the file handle. | Check Windows Task Manager for lingering Folder Lock processes. Try moving the sealed .fld file manually in File Explorer. |

Pause OneDrive sync. Force, close Folder Lock. If persistent, Unlink and Re, link the OneDrive account (Warning: massive resync risk). |

| Dropbox “The file cannot be accessed by the system” | Access control failure due to conflicts between the Dropbox API and permissions set by local security software. | Temporarily pause Dropbox sync. Check Antivirus/Firewall logs for conflicts involving Dropbox or Folder Lock executables. | Add explicit software exceptions for both Folder Lock and Dropbox to the Antivirus/Firewall. Ensure Dropbox client is fully updated. |

| Files appear corrupted or unreadable after download | Synchronization of unsealed data or mixed encryption methods used before upload. | Download the file and check for non, standard encryption headers (e.g., __CLOUDSYNC_ENC__) confirming partial upload. |

Restore the file from the cloud’s previous version history. Strictly limit synchronization only to the final, complete, sealed Locker file. |

| Sync operation is extremely slow (high CPU/RAM use) | High I/O latency introduced by on, the, fly encryption/decryption, particularly on older or resource, limited systems. | Monitor system resource usage in Task Manager during Locker access. Confirm only the sealed Locker file is being tracked by the cloud client. | If using older hardware, consider reducing the KDF iteration count (if permitted by the software, but note this reduces security). Migrate data staging area to an internal drive with higher I/O performance. |

| OneDrive Error: “Sorry, OneDrive can’t add your folder right now” | Folder naming conflict, possibly using system, reserved words or invalid characters prohibited by the sync service. | Rename the folder containing the Locker, removing special characters (like /) and system, specific prefixes such as “windows” or “Windows” (in plural form). |

Relink the OneDrive account, ensuring all folder names comply with current platform naming restrictions. |

6. Essential FAQs (People Also Ask)

Q: How can I recover my data if I forget the Folder Lock master password?

A: If the user is registered, the software serial number provided at purchase often serves as a master key override and can be entered into the password field for recovery. Alternatively, if a password hint or an associated email recovery link was configured, this pathway can be used to reset access. Using any third, party recovery tool is not recommended due to high security risks and unreliable outcomes.

Q: Does my Operating System (Windows/Mac) see my sensitive files when the Locker is open?

A: Yes. While Folder Lock protects data at rest and in transit, when the Locker is mounted as a virtual drive, the operating system treats the decrypted files as standard, locally accessible data. This means that the operating system kernel and any running applications have full visibility of the plaintext contents. Encryption only protects against unauthorized access when the container is sealed.

Q: Is the Folder Lock Locker file truly portable across different computers and OS versions?

A: Yes, the encrypted container file (.fld) is specifically designed to be portable. Because it is a self, contained encrypted binary, it can be copied to a USB drive or synchronized via the cloud, and any other computer running the Folder Lock software (across PC, Mac, iOS, or Android) can access and mount it, provided the user supplies the correct master password.

Q: What is the true security risk of relying only on cloud provider encryption?

A: Cloud providers use server, side encryption, meaning they retain the master keys necessary to decrypt the data. This means the data is not protected from the provider itself, which may be legally compelled to provide access to authorities. Client, side encryption, like Folder Lock’s AES-256 Locker, ensures that the data is encrypted before it leaves the user’s device, maintaining a zero, knowledge standard where the cloud host stores only an unreadable binary block.

Q: Should I use BitLocker or EFS instead of a third, party application like Folder Lock?

A: BitLocker and EFS are highly effective for full, disk encryption and device, level security against theft. However, they are inherently tied to the local machine and user context, making them unsuitable for creating portable, password, protected single, file containers that need to be synchronized and shared across heterogeneous cloud platforms like Dropbox or Google Drive. Folder Lock solves the distinct problem of creating these platform, agnostic, securely transportable vaults.

Conclusion

The key to reliable encrypted cloud synchronization is strict workflow separation. Users must move away from simple file locking, which causes perpetual sync conflicts, and commit to using the sealed Folder Lock Locker container. By ensuring the Locker is fully closed and static before the cloud client attempts synchronization, and by leveraging selective sync to manage storage, professionals achieve both maximum portability and uncompromised AES-256 security. This approach, which treats the secure container as a single, opaque binary, guarantees that the encryption process remains fully isolated from the sync process, solving the core conflict.