Evaluating Encryption, Friendly Clouds: What to Check in 2025

This executive guide, created by the security experts at Newsoftwares.net, provides the definitive framework for selecting a truly encryption, friendly cloud service. To select a truly encryption, friendly cloud in 2025, security decision, makers must look beyond marketing terms and verify three non, negotiable criteria: Zero, Knowledge Key Control, confirmed through external audits; Authenticated Cryptography, ensuring the protocol actively prevents tampering; and Neutral Jurisdiction, placing data residency outside of major surveillance alliances. This strategy ensures verifiable security and maximum data sovereignty for your organization.

To select a truly encryption, friendly cloud in 2025, security decision, makers must look beyond marketing terms and verify three non, negotiable criteria: Zero, Knowledge Key Control, confirmed through external audits; Authenticated Cryptography, ensuring the protocol actively prevents tampering; and Neutral Jurisdiction, placing data residency outside of major surveillance alliances.

Reliance on traditional End, to, End Encryption (E2EE) models is insufficient. Modern threats center on implementation flaws and legal compulsion, meaning verifiable user control over the key encryption key (KEK) is the only reliable defense.

Section 1: Decoding Encryption Buzzwords, The Key Control Gap

In the current digital environment, nearly every cloud service offers encryption. However, security is defined not by the mathematical algorithm used, but by who controls the decryption key. This distinction separates legitimate privacy solutions from standard commercial offerings.

Why End, to, End Encryption (E2EE) Is Often Marketing Noise

End, to, End Encryption is conceptually designed for communication between two distinct parties, a sender and a recipient, such as in a messaging app. In the context of cloud storage, where the user is often both the sender and the recipient accessing data from various devices, the E2EE nomenclature does not fit precisely.

The fundamental risk is that many providers claiming E2EE still retain control over the encryption keys, or store wrapped keys that they can access under certain legal or technical circumstances. If the service provider holds the encryption keys, the E2EE chain can still be compromised. This practice nullifies the security benefit, as the provider can be compelled by subpoena or breached by a rogue employee.

Zero, Knowledge Encryption (ZKE) is the Standard

Zero, Knowledge Encryption represents the necessary evolution for cloud storage security. ZKE is a policy and a commitment guaranteeing that the service provider does not store, access, or know the user’s encryption keys.

With ZKE, data is secured with a unique user key which the app developer never knows. This means that even if a provider were legally compelled or technically breached, they could only provide meaningless ciphertext, ensuring total privacy because only the user has control over the keys.

Client, Side Encryption (CSE) as Implementation

Client, Side Encryption (CSE) is the technical mechanism that achieves the ZKE guarantee. CSE requires data to be encrypted on the user’s local device before it is transmitted to the cloud server.

This process ensures that data exposure is drastically reduced during transmission. When CSE is used with a service like Google Cloud Storage (GCS), the data arrives at the cloud server already encrypted. GCS then typically encrypts the data a second time, referred to as Server, Side Encryption (SSE), which GCS manages. This second layer of encryption is irrelevant to the user’s privacy since the critical client, side layer remains inaccessible to the provider. The user must manually decrypt the client, side layer upon retrieval.

This model creates a technical barrier against legal and internal compromise. If the encryption key is exclusively user, owned, the provider cannot physically execute a legal order demanding access to plaintext, establishing a crucial technical defense against data compulsion, such as requests under the CLOUD Act.

Section 2: The Three Non, Negotiable Pillars of Cloud Security

For professionals and organizations, validating true encryption readiness requires a detailed examination of three core pillars: key ownership, cryptographic integrity, and jurisdictional safety.

2.1. Pillar 1: Key Management and Ownership (The Control Hierarchy)

Organizations using large commercial cloud providers (hyperscalers like AWS or GCP) often utilize specialized encryption models designed for enterprise control. These models move key management away from the provider’s default Server, Side Encryption (SSE).

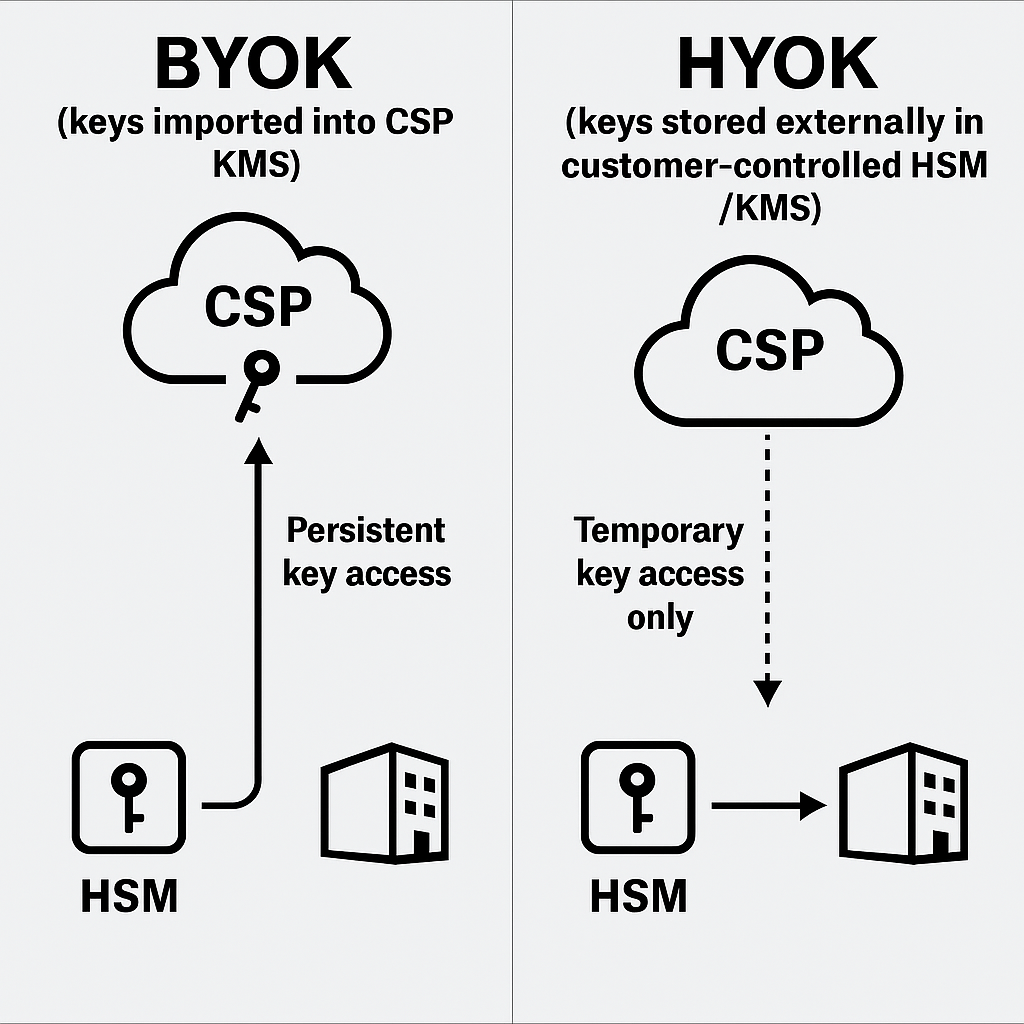

The Enterprise Standard: BYOK vs. HYOK

For highly regulated or sensitive data, organizations must define who controls the Key Encryption Key (KEK), the master key used to protect all Data Encryption Keys (DEKs). This leads to two primary enterprise models: Bring Your Own Key (BYOK) and Hold Your Own Key (HYOK).

- BYOK (Bring Your Own Key): In this model, the customer generates the encryption key but then imports it into the Cloud Service Provider’s (CSP) Key Management System (KMS). Control is considered shared, as the CSP stores and manages the keys after import. While this enables policy enforcement and compliance, the CSP retains persistent access to the key material, limiting the separation of duties. This is suitable for organizations with moderate control requirements.

- HYOK (Hold Your Own Key): This model offers the highest level of security and control. The customer generates the keys and stores them externally, typically in a customer, controlled data center or a third, party KMS that is physically and logically separate from the CSP. The CSP only requests temporary access to the keys for specific operations (encryption/decryption) and then purges them immediately. This strong separation of duties provides a robust compliance posture and maximum customer control. This operational model mirrors the zero, knowledge principle in an enterprise environment.

Regardless of whether an organization chooses BYOK or HYOK, responsibility for key management policies, defining user and administrator roles, and enforcing least privilege falls to the customer. Best practices for managing keys used to encrypt highly sensitive data mandate the use of a validated Hardware Security Module (HSM).

Table 1: Key Control Model Comparison: BYOK vs. HYOK

| Feature | BYOK (Bring Your Own Key) | HYOK (Hold Your Own Key) |

| Key Generation | Customer generates the keys | Customer generates the keys |

| Key Storage | Imported into CSP’s KMS | Stored externally (Customer/Third, Party KMS) |

| CSP Persistent Key Access | Yes (CSP stores and manages post, import) | No (CSP only requests temporary access) |

| Control Level | Moderate (Shared control) | Maximum (Full customer control) |

| Suitable For | Organizations with moderate control requirements | Highly regulated industries needing strong separation of duties |

2.2. Pillar 2: Cryptographic Integrity and Protocol Audits

Strong encryption is necessary but insufficient. In 2025, the primary threat is not cipher breakage, but implementation failure. A provider must demonstrate protocol integrity through external, verifiable security audits.

The KDF Mandate

The AES-256 cipher remains the industry standard for symmetric data encryption. However, the security of user, derived keys hinges on the Key Derivation Function (KDF). The KDF generates the cryptographic key from the user’s password. This function must be engineered to be computationally intensive to defeat brute, force attacks.

For example, services like Tresorit use PBKDFv2. A well, tuned KDF requires a computer to spend a small but significant amount of time (e.g., 200ms) to derive the key from a password. This delay quickly becomes astronomically high if an attacker attempts to try every potential password. If a provider uses a weak or rapid KDF, specialized hardware (like ASICs) can rapidly compromise the user key, regardless of the AES-256 cipher strength.

The 2024 Flaw Reality Check

Recent security audits have highlighted critical implementation failures among major E2EE cloud providers, proving that written security white papers do not guarantee flawless execution. These flaws generally hinge on a malicious server being able to confuse or corrupt the client application during synchronization.

Key vulnerabilities observed in 2024 included:

- Unauthenticated Key Material: Both Sync and pCloud were found to be vulnerable because they did not properly authenticate encryption keys, potentially allowing an attacker to insert their own keys, thus compromising the confidentiality of stored files.

- Metadata Tampering: This widespread vulnerability affects nearly all major providers studied, including Sync, pCloud, Seafile, Icedrive, and Tresorit. Attackers can tamper with file metadata, such as file names, location, or modification dates. Since metadata is often poorly encrypted (or not encrypted at all) to facilitate basic cloud operations like searching and indexing, this flaw allows a malicious server to break confidentiality or inject corrupted files.

- Protocol Weaknesses: Providers like Seafile were cited for encryption protocol downgrade vulnerabilities, and Icedrive and Seafile were noted for using unauthenticated encryption modes like CBC.

The prevalence of these flaws confirms that while companies like Tresorit publish strong cryptographic details, including the use of AES-256 and RSA-4096, strong paper security is secondary to the technical proof provided by external, independent audits.

Table 2: Critical Flaws Found in E2EE Cloud Storage (2024 Audit)

| Attack Scenario/Flaw Type | Description of Vulnerability | Affected Providers (Examples) |

| Lack of Key Material Authentication | Attackers insert their own keys, compromising file confidentiality. | Sync, pCloud |

| Unauthenticated Public Key Use | Adversaries replace legitimate keys during file sharing/collaboration. | Sync, Tresorit |

| Metadata Tampering | Changing file names, location, or modification dates without detection. | Sync, pCloud, Seafile, Icedrive (All five providers studied) |

| Encryption Protocol Downgrade | Forcing weaker cryptographic modes for data handling. | Seafile |

2.3. Pillar 3: Jurisdictional Risk and Legal Pressure (GEO Factor)

The physical location of the cloud provider and the jurisdiction of data residency play an increasingly vital role in security due to legislative action.

The CLOUD Act and Compulsion

The U.S. CLOUD Act (Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data) applies broadly to electronic communication services and remote computing services, potentially compelling disclosure of data stored anywhere in the world, even if that data resides outside the U.S.. While the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) advises prosecutors to seek data directly from the customer first, this policy is not a blanket guarantee of protection.

Furthermore, international pressure to break encryption is intensifying. A February 2025 report detailed the UK Home Office attempting to compel Apple to introduce a back door into its end, to, end encrypted cloud storage service, Advanced Data Protection (ADP). Cybersecurity experts universally agree that introducing a governmental backdoor creates a systemic security flaw that can be exploited by criminals and nation, state actors alike.

The Privacy Hedge: GDPR and Neutral States

Jurisdictional choice provides a critical legal defense. Regulations like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) dictate strong policies on data residency and require businesses to protect sensitive data (PII). GDPR compliance includes enforcing cross, border data transfer restrictions.

Choosing providers headquartered in countries with robust privacy protections, such as Switzerland (used by Proton Drive and pCloud’s European operations) or other EU nations, provides a stronger legal hedge. If a provider cannot access the key material due to technical constraints (ZKE) and operates under a strong regulatory regime (GDPR), the legal risk of compelled plaintext disclosure drops significantly.

Section 3: Practical Vetting: Commercial Zero, Knowledge Options

For organizations seeking a managed solution that adheres to the ZKE criteria, thorough vetting is necessary due to the recent discovery of implementation flaws.

Evaluating Commercial Zero, Knowledge Providers

- Sync.com: Although Sync positions itself as a private cloud storage solution and claims end, to, end protection, its transparency is highly problematic. Sync lacks ISO certifications and GDPR, specific audits. Most critically, the company offers unclear communication regarding key management, failing to explain precisely where decryption keys are generated and stored. This lack of verifiable explanation causes reviewers to doubt that Sync offers true zero, knowledge end, to, end encryption. Sync was also cited in the 2024 security audits for allowing unauthenticated key material and metadata tampering.

- Proton Drive: Headquartered in Switzerland, Proton Drive operates an open, source model that integrates security across its ecosystem (Mail, VPN). The service is strong on privacy and jurisdiction. However, user experiences indicate significant speed variability, particularly when synchronizing large numbers of small files. While large file uploads (e.g., a 2GB ZIP file) can be fast once initiated, the overall speeds can be an order of magnitude slower (20, 40 Mbps) than traditional clouds (100, 300 Mbps). This highlights the inherent trade, off between local encryption overhead and synchronization performance.

- Internxt: This provider focuses heavily on security, offering zero, knowledge and even implementing advanced, post, quantum encryption features. Internxt is regularly audited by third parties like Securitum, providing verifiable proof of work. Performance testing showed that the encryption process had minimal detrimental impact on upload speeds (e.g., 625MB uploaded in 1 minute 55 seconds), suggesting highly efficient client, side implementation. Its main limitation is a lack of the deep integrations often found in major platforms like Google Workspace or Microsoft 365.

- Tresorit: Tresorit is highly robust and often considered enterprise, grade, utilizing strong cryptographic standards like AES-256 and RSA-4096, and providing details on its KDF (PBKDFv2). Despite this strong internal security documentation, the 2024 audits cited Tresorit for implementation flaws involving the use of unauthenticated public keys during sharing. This demonstrates that even the most technically robust providers are not immune to synchronization vulnerabilities.

- MEGA: MEGA offers substantial free storage and utilizes E2EE. However, the provider has received criticism regarding its content scanning practices. The service scans publicly shared files for copyright infringement, which, to many privacy, conscious users, indicates that the service retains some ability or method to inspect or derive information about the file contents, fundamentally compromising the definition of zero, knowledge.

Performance and Security Vetting Matrix

The decision between commercial providers depends heavily on the organizational tolerance for implementation risk versus the need for collaboration features and raw speed.

Table 3: Zero, Knowledge Provider Feature Matrix (Use, Case Chooser)

| Feature | Tresorit | Proton Drive | Sync.com | Internxt | MEGA |

| Zero, Knowledge Status | Verified, Strong Cryptography | Open, Source, Verified | Questioned (Key management unclear) | Verified, Quantum, Safe | Strong (Compromised by content scanning) |

| Compliance/Jurisdiction | GDPR/Switzerland/Hungary | GDPR/Switzerland | PIPEDA/Canada (Lacks GDPR Audits) | GDPR/EU | EU |

| Metadata Encryption | Yes (File name, date, key stored encrypted) | Yes (Open, source verified) | Unclear/Suspect | Yes (Named in tamper audit) | Yes |

| Observed Speed (Large Files) | Robust | Slower initiation, moderate transfer speed | Moderate/Suspect | Held up well, encryption impact low | Moderate/Slow |

| Critical Flaw Mention (2024) | Yes (Unauthenticated Public Keys) | No (Not in audit scope) | Yes (Unauthenticated Keys/Metadata) | Yes (Unauthenticated modes/Metadata) | No (Not in audit scope) |

Section 4: DIY Zero, Knowledge: Implementing Client, Side Encryption (Tutorial)

The maximum level of verifiable control is achieved when an organization implements its own Client, Side Encryption (CSE) scheme using a controlled Key Management System (KMS), effectively creating an HYOK environment within a commodity cloud. The following tutorial uses Google Cloud Storage (GCS) as the backend and the Tink cryptographic SDK, an open, source solution provided by Google, to manage the encryption locally.

Outcomes Summary

The objective of this method is to retain full ownership of the master encryption key while storing data in a hyperscaler cloud environment:

- Data is encrypted locally using the open, source cryptographic SDK, Tink.

- The Data Encryption Keys (DEKs) are protected using a master Key Encryption Key (KEK) stored securely in Cloud KMS.

- The resulting ciphertext is uploaded to GCS, ensuring the CSP has no knowledge of the plaintext or the DEK.

4.1. Prerequisites and Key Safety

This method transfers 100% of the key management risk to the customer.

- Prerequisites: A dedicated Python environment must be established, and the necessary libraries must be installed: Tink cryptographic library, Google Cloud KMS client library, and Google Cloud Storage client library. A symmetric Cloud KMS encryption key (KEK) must be created, and its full Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) must be noted. A dedicated Cloud Storage bucket must also be created.

- Mandatory Warning: If the client, side key or the master KEK is forgotten or lost, the data becomes permanently irretrievable. The CSP (Google) has no mechanism to recover the key or the encrypted data. The customer will continue to incur storage charges for the unreadable objects until they are manually deleted.

4.2. Setup: IAM Roles and Credentials

Authentication and role assignment are the most common initial failure points.

- Key Step: Role Grant: To allow the automation to function, the organization must grant its service account the specific Cloud KMS CryptoKey Encrypter/Decrypter role (

roles/cloudkms.cryptoKeyEncrypterDecrypter) on the KEK. - Crucial Caveat: This role must be granted to the service account that your application uses for cloud communication, not to your user account. This enforces the critical security practice of separation of duties and least privilege, ensuring that human administrators do not have routine access to the cryptographic operations.

4.3. Step, by, Step: Client, Side Envelope Encryption (Conceptual Steps)

Envelope encryption uses the high, security KEK (in KMS) sparingly, only to wrap (encrypt) the smaller, faster, performing DEK. The DEK is generated locally by Tink and performs the actual file encryption, maximizing speed and minimizing latency with the remote KMS.

- Initialize Tink and Client Libraries: Initialize the Tink AEAD primitive using

aead.register(). Set up the GCP KMS client and the GCS client, authenticating both using the service account credentials. - Define the KEK URI: The system must receive the full KMS key URI, which identifies the master KEK used for key wrapping:

gcp-kms://projects/PROJECT_ID/locations/LOCATION/keyRings/KEY_RING/cryptoKeys/KEY_NAME/cryptoKeyVersions/KEY_VERSION. - Create Remote AEAD Primitive: Obtain the remote AEAD object for the KEK URI:

remote_aead = client.get_aead(FLAGS.kek_uri). - Create Envelope AEAD Primitive: Instantiate the local envelope AEAD primitive, combining a local symmetric cipher (e.g., AES256 GCM) with the remote AEAD:

env_aead = aead.KmsEnvelopeAead(aead.aead_key_templates.AES256_GCM, remote_aead). - Define Associated Data (Integrity Check): Define the associated data (

associated_data), typically the GCS blob path, which is bound to the encryption process. This step is vital for ensuring integrity and preventing metadata tampering attacks. - Read Plaintext: Open the local input file and read its contents.

- Execute Encryption: Encrypt the data using the envelope AEAD:

output_data = env_aead.encrypt(input_file.read(), associated_data). This single call automatically performs the DEK generation, data encryption, DEK wrapping with the KEK, and package creation. - Upload Ciphertext: Upload the resulting encrypted

output_datato the GCS bucket.

4.4. Decryption and Verification

- Download Ciphertext: Retrieve the encrypted blob from the GCS bucket.

- Execute Decryption: Use the same envelope AEAD primitive and associated data to decrypt the ciphertext:

env_aead.decrypt(ciphertext, associated_data). Tink manages the process of contacting KMS to unwrap the DEK and then decrypting the file locally. - Verification (Proof of Work): Once decrypted, the original file is retrieved. In GCS, the object’s properties will confirm that the data size matches the uploaded ciphertext size and that the object is stored without the client, side key being known to Google.

4.5. Key Rotation and Revocation Strategy

Robust security requires a detailed plan for key compromise or retirement.

- Key Revocation: If a Key Encryption Key is suspected of unauthorized use, the response plan must be executed immediately: re, encrypt all data protected by that KEK using a newly generated key, revoke the IAM access associated with the compromised key, and disable or schedule destruction of the compromised key version.

- Destruction Schedule: Key destruction is generally irreversible, which is why KMS services incorporate a mandatory delay. In Google Cloud KMS, destroying a key version schedules it for deletion, typically 30 days later. During this

scheduled for destructionwindow, the key can be restored, providing a safety net against accidental data loss. After the period expires, the key material is permanently deleted, rendering all associated data unreadable. Security administrators must integrate this window into governance procedures.

Section 5: Troubleshooting and Disaster Prevention

Even with the best cryptographic protocols, failures often occur at the local configuration or synchronization layer. Troubleshooting must address both administrative key management errors and common client, side sync failures.

5.1. Symptom $\to$ Fix: Common Sync and Provisioning Failures

The adoption of ZKE/CSE shifts the risk profile, making local configuration errors more critical, as the cloud provider cannot intervene to fix data access issues.

Table 4: Troubleshooting Common Client Sync and Provisioning Errors

| Symptom/Error String | Root Cause | Non, Destructive Fix | Last Resort (Data Loss Warning) |

| Failed to provision device or Internal server error | Incompatible drive format (e.g., exFAT instead of required NTFS) or temporary server outage. | Check drive format and ensure it meets provider requirements (e.g., NTFS for Sync CloudFiles). Wait 5–10 minutes and check the provider status page. | Re, provision the device after confirming credentials and correct drive format. |

| Files stuck Indexing or not appearing across devices. | Local disk space shortage, or antivirus/firewall blocking the client’s connection. | Confirm local device has sufficient storage (must match file size plus processing overhead). Allow the client app through security software. | Manual update to the latest client application version. Clean re, provisioning. |

| Data is unreadable after key loss or deletion. | Client, side encryption key was permanently lost, destroyed, or revoked. | Attempt key restoration within the KMS scheduled destruction window (e.g., 30 days). | Data is permanently irretrievable, the only option is to delete the ciphertext objects from storage. |

| Errors syncing changes in shared folders. | The cloud provider may lack automatic change notifications or journaling, especially for large server endpoints. | Manually force a sync session or wait for the client application’s next scheduled check, in. | N/A |

5.2. Root Causes of Unrecoverable Data Loss

The ultimate vulnerability in a ZKE/CSE system is the integrity of the key management process, which is entirely the user’s responsibility.

- Irreversible Key Loss: Losing the client, side master password or key material for ZKE data is the most critical threat. Since the provider cannot decrypt the data or recover the key, the encrypted files are permanently inaccessible.

- Human Error and Misconfiguration: Human error remains one of the most frequent causes of security incidents in the cloud. For ZKE, this includes improper configuration of drive formats (like using exFAT instead of NTFS) or mismanaging service account roles, which can prevent the system from encrypting or decrypting data correctly.

- Key Destruction: Purposely or accidentally destroying a key version in a KMS without proper backups is final. After the 30, day scheduled destruction window expires, the key material is cryptographically wiped, resulting in permanent data loss for all associated files.

Section 6: FAQ: People Also Ask (PAA)

What is the difference between encryption, at, rest and ZKE

Encryption, at, rest scrambles data while it is stored on the server, but the provider still retains access to the decryption key. ZKE (Zero, Knowledge Encryption) means data is encrypted on your device (client, side) using a key the provider never sees, ensuring privacy even from the host.

Does strong encryption slow down file transfers significantly

Yes, E2EE inherently requires local processing overhead (encryption, key wrapping, integrity checks). This effect is most noticeable when synchronizing a large volume of small files. However, providers like Internxt have demonstrated highly optimized implementations where the speed impact on large files is low.

If a cloud service is based in the EU, is it automatically safe from the CLOUD Act

No. The U.S. CLOUD Act applies to all electronic communication services, regardless of where they are incorporated, if they serve U.S. customers or have U.S. business ties. Strong local privacy laws like GDPR and genuine ZKE key control provide the best technical and legal defense.

How can I confirm if a ZKE provider is legitimate

Legitimacy requires proof of work beyond marketing claims. Look for public, third, party security audits (e.g., by Securitum) that specifically review the cryptographic protocol. Also, demand transparency regarding the Key Derivation Function (KDF) details and evidence that file metadata is encrypted.

Is AES/Rijndael encryption the same as AES-256

AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) is the cipher standard, derived from the Rijndael algorithm. AES-256 refers to the key length (256 bits). For modern, professional cloud security, AES-256 is the minimum acceptable standard due to its cryptographic strength.

Why do audit reports frequently mention metadata tampering

Metadata (file name, size, modification date) is often poorly protected to allow cloud servers to maintain functionality like searching and indexing. Tampering with this allows a malicious server to redirect file IDs or confuse the client, compromising file confidentiality and integrity.

What is the practical risk of using Sync.com given the audit concerns

The primary risks stem from Sync’s lack of verifiable key control and implementation flaws cited in recent audits, specifically regarding unauthenticated key material and metadata tampering. This means that a sophisticated attacker controlling the cloud server might be able to compromise confidentiality despite the files being encrypted.

Can I use a commercial ZKE service for GDPR compliance

Yes, a ZKE service strongly supports GDPR compliance because it enforces data protection by design, specifically regarding separation of duties. Provided the service allows enforcement of data residency within the EU (if PII requires it) and uses verifiable zero, knowledge principles, it satisfies GDPR’s mandate for data protection.

What is the risk of using a service like MEGA that scans files for copyright

Any service claiming zero, knowledge but reserving the ability to scan file contents (even via hash checks) inherently compromises the zero, knowledge principle. This suggests the service maintains some access or derivation method that contradicts the guarantee that only the user can know the contents.

Is it safer to build my own CSE solution (like Tink/KMS) than using a commercial service

For maximum administrative control and strict separation of duties (HYOK model), DIY CSE is superior. However, this transfers 100% of the risk (especially key management and loss) to the organization. Commercial ZKE solutions offer a balance of security and usability, provided they are externally audited and their key protocols are proven.

Why is two, factor authentication (2FA) critical, even with ZKE

ZKE protects the files from the provider. 2FA protects your account access from hackers. Since account breaches (often resulting from compromised user credentials) are a major source of security failure, 2FA must be considered a mandatory layer of defense.

What happens if I disable or destroy a key in Google Cloud KMS

The key material is immediately scheduled for permanent destruction. Data encrypted with that key becomes instantly unreadable. After the scheduled destruction period (defaulting to 30 days), the key is irreversibly deleted, making the data permanently inaccessible.

Is E2EE necessary for securing data during transfer (in, transit)

Yes, E2EE protocols (or transport layer security protocols like TLS) are essential to protect data from interception as it moves across the network. However, securing data in, transit does not guarantee privacy at rest if the provider retains the decryption keys.

How often should I rotate my KMS encryption keys

Key rotation frequency depends heavily on regulatory compliance requirements (e.g., HIPAA, PCI). As a baseline best practice, rotation should occur annually or immediately upon suspicion of key compromise to limit the data exposure window.

Does client, side encryption offer protection against rogue employees at the cloud provider

Yes. This is the core operational defense of ZKE/CSE. Because the provider’s employees, including system administrators, do not possess the client, side encryption key, they are technically unable to decrypt the data, offering protection against insider threats.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The analysis of cloud encryption in 2025 demonstrates a critical security gap between marketing claims and verifiable implementation. The fundamental shift in data protection is moving away from trusting a provider’s policy (even E2EE) toward establishing technical assurance through exclusive key ownership.

For organizations requiring the highest level of data confidentiality, two pathways offer verifiable security:

- Enterprise Control (HYOK): Implementing a custom Client, Side Encryption solution using an isolated Key Management System (KMS) and open, source tools like Tink. This achieves the maximum level of control, enforces separation of duties, and places the technical defenses of zero, knowledge entirely within the organization’s purview. This solution is required for entities operating under strict regulatory regimes.

- Commercial Verification (Audited ZKE): Selecting a commercial Zero, Knowledge provider that submits to frequent, public, third, party security audits (like Internxt or verified systems like Tresorit, despite historical implementation notes). It is mandatory to choose providers based in privacy, friendly jurisdictions, such as Switzerland, which offer an increased buffer against legal compulsion attempts under the CLOUD Act or similar foreign statutes.

Any cloud service whose key management process is opaque, failing to detail how keys are derived, authenticated, and stored (as observed with Sync.com), must be considered unsuitable for sensitive data. Security in 2025 is predicated on verifiable cryptographic proof, not proximity to the data.