End-to-End Encrypted Sync vs Encrypted at Rest : The Big Differences in Data Sovereignty

This executive guide, prepared by the security experts at Newsoftwares.net, provides the definitive comparison of cloud encryption models. The fundamental difference between End-to-End Encrypted Sync (E2EE), which requires Client-Side Encryption (CSE), and standard “Encrypted at Rest” (Server-Side Encryption, or SSE) is the location and control of the decryption key. SSE requires the user to trust the cloud vendor because the provider controls the key and can access plaintext data whenever necessary. E2EE establishes a zero-knowledge standard by encrypting data locally on the device, ensuring the vendor receives only scrambled ciphertext and possesses no mechanism to decrypt it. This distinction is critical for any entity bound by regulatory compliance or concerned with data sovereignty, ensuring verifiable data security and user control.

The fundamental difference between End-to-End Encrypted Sync (E2EE), which requires Client-Side Encryption (CSE), and standard “Encrypted at Rest” (Server-Side Encryption, or SSE) is the location and control of the decryption key. SSE requires the user to trust the cloud vendor because the provider controls the key and can access plaintext data whenever necessary. E2EE establishes a zero-knowledge standard by encrypting data locally on the device, ensuring the vendor receives only scrambled ciphertext and possesses no mechanism to decrypt it.

This distinction is critical for any entity bound by regulatory compliance or concerned with data sovereignty, as key control determines who can ultimately read the files, the user or the cloud service infrastructure.

Key Takeaways: Why the Distinction Matters Summary

- Key Control: E2EE grants the client device absolute data sovereignty; SSE grants the vendor centralized key management control necessary for platform usability and automated recovery.

- Metadata Visibility: SSE exposes critical file metadata, including names, folder structure, and access timestamps; E2EE tools are specifically engineered to obfuscate this sensitive information.

- Operational Friction: E2EE demands higher user technical competence due to manual key management, making collaboration, web access, and automated recovery far more complex than standard cloud workflows.

Understanding Encrypted at Rest (SSE): The Vendor Trust Model

Server-Side Encryption (SSE) is the dominant form of security adopted by mainstream cloud storage platforms like Dropbox, Google Drive, and AWS S3. While robust against external threats, SSE operates on a principle of shared trust, where the user implicitly trusts the provider to handle the decryption keys responsibly.

How SSE Functions and the Trust Gap

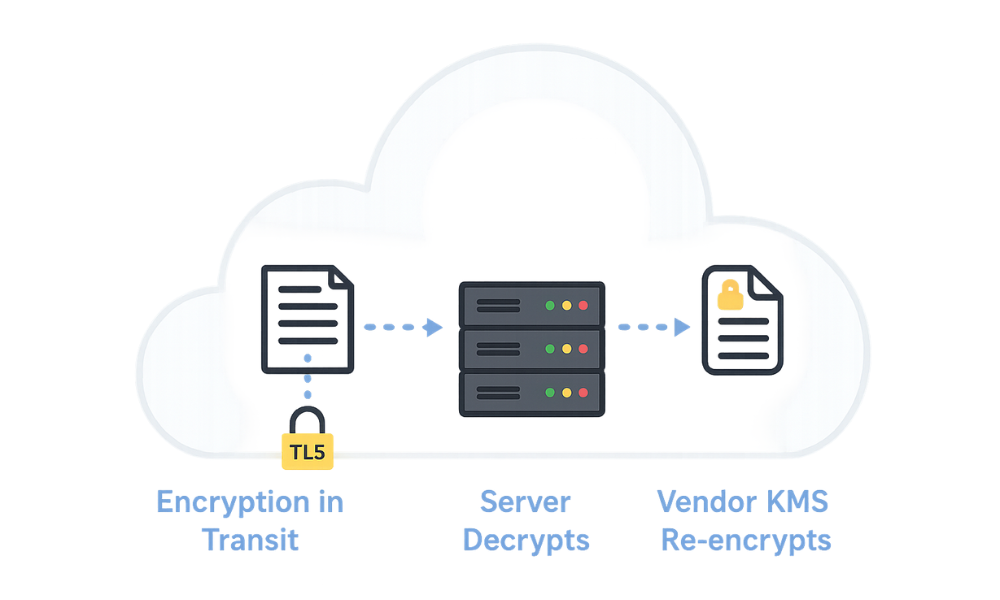

In a typical SSE scenario, the client sends data over a secure channel established by Transport Layer Security (TLS/SSL). This process, often called “encryption in transit,” successfully protects data from external attackers monitoring the network wire. However, once the data reaches the cloud server, the server immediately decrypts it. This step is necessary for the cloud platform to perform essential functions such as indexing, search, virus scanning, real-time collaboration, and data processing.

The data is only encrypted after the server has processed the plaintext content. It is then encrypted using keys managed by the vendor’s internal Key Management Service (KMS) before being written to the physical storage device. This safeguards the data against physical theft of the storage devices, but it leaves the data vulnerable to access by the cloud provider’s internal staff, administrative processes, or in response to legal or government compulsion. If the server handles both encryption and decryption, the privacy guarantee fails against the host itself.

The Role of Cloud Key Management Services (KMS)

Major cloud platforms centralize the cryptographic key lifecycle management using internal services such as AWS Key Management Service (KMS) or Google Cloud KMS. These systems are responsible for generating, storing, and controlling access to the master key material used for data encryption.

For large enterprise customers subject to stringent compliance requirements, providers offer Customer Managed Keys (CMK). A CMK allows the customer to define policies surrounding the key, such as key rotation schedule, usage permissions, and access policy grants. This gives customers better administrative control over the key lifecycle and can help meet certain compliance requirements.

However, this elevated control must not be confused with true end-to-end privacy. The key material, even when defined as customer-managed, remains inside the cloud provider’s highly secured infrastructure, managed and operated by the provider’s KMS service. The critical point is that the decryption operations are still executed within the vendor’s environment. While advanced features like Google’s Key Access Justifications offer visibility into key usage requests, the ultimate authority to execute the decryption action still rests within the cloud platform’s operational boundary. Therefore, standard SSE, even with CMKs, does not uphold the zero-knowledge principle.

SSE Facilitates Features, E2EE Hinders Them

The choice of SSE is fundamentally an architectural decision driven by feature enablement. Cloud service vendors depend on plaintext access to deliver core functionalities: instant file search, document indexing, automated content analysis, and real-time collaboration features like those found in Google Docs or Dropbox Paper. SSE is the only encryption strategy that permits the server to access the content and fulfill these complex service roles.

For users prioritizing convenience, seamless integration, and vendor-assisted recovery, SSE is the default and appropriate choice. The necessary trade-off is accepting that the cloud provider, their administrators, and specific legal authorities may be able to read the data at rest.

Table I summarizes the core differences between the two security paradigms.

Table I: E2EE Sync vs. Encrypted At Rest

| Security Factor | E2EE Sync (Client-Side) | Encrypted At Rest (Server-Side) |

| Key Control & Access | User holds the key; zero-knowledge for vendor. | Vendor holds the key; keys accessible by the vendor’s KMS. |

| Data Visibility (Plaintext) | Only visible on authorized client devices. | Visible to the server (provider staff, legal requests) before encryption. |

| Metadata Protection | Filenames, structure, and timestamps are obfuscated. | Filenames, timestamps, and structure are logged and readable by the vendor. |

| Web Interface Access | Generally unavailable or limited (client decryption required). | Full web preview, search, and indexing capability. |

| Risk of Data Loss | High if master key or password is lost. | Minimal—vendor can usually recover data based on centralized key management. |

True Privacy: End-to-End Encrypted Sync (E2EE/CSE)

End-to-End Encryption (E2EE), interchangeable with Client-Side Encryption (CSE) in this context, is the mechanism required for true data sovereignty. E2EE ensures the data is encrypted at the source device and remains encrypted until it reaches the authorized destination device, preventing any intermediate party, including the service provider, from accessing the plaintext.

The Zero-Knowledge Principle: Trusting Math, Not Companies

The E2EE model is built on the zero-knowledge principle: the provider, by design, has no means to access the actual content. This strategy removes the necessity of trusting the cloud vendor’s legal or internal security integrity. The data’s security relies entirely on the strength of the cryptography and the security of the user’s local device, shifting the trust from the corporation to the mathematics of the cipher itself.

The mechanism requires that data is encrypted before it leaves the client’s machine. The master decryption key is stored exclusively on the client device or derived from a strong passphrase the server never receives or stores. This approach is standard in high-security communications (Signal, WhatsApp) and sync utilities (Cryptomator, rclone crypt).

Technical Standards: The Modern Security Stack for E2EE

Effective E2EE is highly dependent on rigorous cryptographic standards. Flawed implementation, or reliance on deprecated standards, renders the entire security architecture useless.

Modern Ciphers

For symmetric content encryption, the actual scrambling of file data, the current industry standard is AES-256 GCM (Advanced Encryption Standard with 256-bit keys in Galois/Counter Mode). GCM is preferred because it provides authenticated encryption, meaning it confirms both the confidentiality and integrity of the data. Older symmetric modes, such as AES-256 CBC or the older Rijndael CBC, are generally discouraged due to known security risks and a lack of built-in authentication capabilities.

Key Derivation Functions (KDF)

User passwords alone are insufficient for cryptographic defense. They must be strengthened using a robust KDF to mitigate offline brute-force attacks. The password, or passphrase, is run through a KDF to derive the actual Key Encryption Key (KEK). The preferred modern choices for KDFs are Scrypt or PBKDF2 with a very high iteration count (typically 100,000 or more). Cryptomator, for instance, utilizes Scrypt to derive the KEK, which is then used to securely wrap the vault’s master keys.

Envelope Encryption for Efficiency

To handle large files efficiently, E2EE sync clients use envelope encryption. The client generates a random, single-use Data Encryption Key (DEK) to encrypt the large file content. The DEK itself is then quickly encrypted using the KEK derived from the user’s master password. The combination of the encrypted file and the encrypted DEK is stored in the vault. This two-tiered approach balances the speed of symmetric encryption (using the DEK) with the security of the KEK protecting that DEK.

Hidden Risks: Metadata Leakage and Obfuscation

The most subtle and potentially catastrophic failure of standard Encrypted at Rest (SSE) is the total exposure of file metadata. Security professionals recognize that even if the content remains sealed, the patterns revealed by metadata, the who, what, and when, can compromise privacy as effectively as accessing the plaintext.

The Filesystem Leak: What Your Cloud Knows

Cloud providers must log extensive metadata to facilitate synchronization, billing, and system auditing. This logged data provides a complete record of user activity that is readable by the vendor and any party with legal access to their records.

Critically, the cloud provider logs the full plaintext filename, the exact folder structure, file creation and modification timestamps, and the IP address from which the upload or request was made. This exposure enables highly effective statistical and behavioral tracking. For instance, observing that files within a folder named “Acquisition Target Due Diligence” were modified consistently between 1 AM and 3 AM from an IP address traced to a competing company’s office provides significant actionable intelligence, even if the file content itself is encrypted. The threat, in this case, is not brute-forcing the encryption cipher, but rather performing mass surveillance and inference based on behavioral patterns established by the metadata logs.

How E2EE Tools Obfuscate Names and Structure

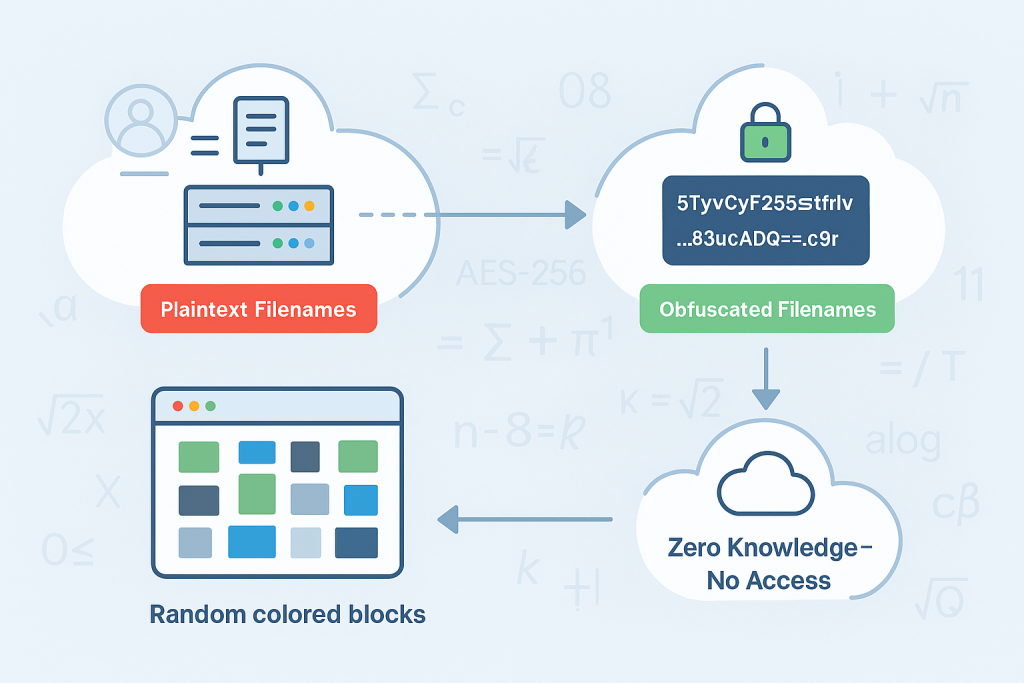

Effective E2EE sync tools, such as rclone crypt or Cryptomator, are designed specifically to defeat metadata leakage by executing obfuscation on the client device. This process is essential for maintaining privacy.

- Filename Encryption: Filenames are transformed using strong cryptography, replacing readable identifiers (e.g., “Project_Titan_Budget.pdf”) with long, randomized strings or hashes, such as

5TyvCyF255sRtfrIv...83ucADQ==.c9r. - Directory Structure Protection: The logical hierarchy of folders is also protected. E2EE tools encrypt the directory names and store file-key mappings within specialized encrypted vault structure files. The cloud provider only sees a flat, unreadable collection of cryptographic containers.

This process ensures that the server cannot link an observed modification time or IP address to a specific, meaningful plaintext file name or directory, thereby mitigating the risk of statistical analysis. It is important to acknowledge, however, that the file size always remains visible. Significant changes in the size of the encrypted blob can still reveal that a major content change occurred, though the specifics remain unknown.

Table II illustrates the fundamental difference in what information is exposed depending on the encryption model used.

Table II: Metadata Visibility Matrix

| Metadata Field | Visible to Cloud Provider (SSE) | Hidden from Cloud Provider (E2EE/CSE) |

| File Name | Yes (Plaintext) | No (Obfuscated hash) |

| Folder Structure | Yes (Plaintext) | No (Obfuscated structure) |

| File Size | Yes (Plaintext size of ciphertext) | Yes (Plaintext size of ciphertext) |

| Modification Time | Yes (Plaintext timestamp of encrypted file modification) | Yes (Plaintext timestamp of encrypted file modification) |

| IP Address of Upload | Yes (Plaintext) | Yes (Plaintext client IP is always visible) |

Practical Implementation: Setting Up Zero-Knowledge Sync (How-To Tutorial)

Implementing E2EE sync requires using a dedicated client application to manage a local encrypted vault that synchronizes ciphertext data to a standard cloud service (like Dropbox or Google Drive). This method effectively uses the cloud provider solely as untrusted storage infrastructure.

Prerequisites and Safety Protocols

Before initiating E2EE, users must adhere to strict safety protocols, as key loss results in permanent data loss.

- Mandatory Key Backup: The risk of data loss is absolute if the master key or vault password is forgotten or destroyed. A robust, geographically separated backup strategy for the password or the vault’s master key file is non-negotiable. This often involves a secure, physical location or an encrypted memory stick separated from the primary storage environment.

- Trusted Computing Base: The device performing the encryption must be trusted. If the operating system or device is compromised by malware, the E2EE mechanism is defeated before encryption even occurs.

- KDF Verification: If using command-line tools or legacy software, verify that the Key Derivation Function parameters are correctly implemented. OpenSSL versions 1.1.1 or later should use options like

-pbkdf2 -iter 100000to ensure the key is adequately stretched and resistant to modern brute-force techniques. - Keyboard Layout Caution: Users who switch between keyboard languages or layouts must exercise extreme caution when setting the initial vault password. Certain special characters (such as accent marks or apostrophes) behave differently depending on the active layout, leading to unexpected character conversions. If the layout is wrong upon subsequent decryption attempts, the key derivation will fail and the data will be inaccessible.

Steps for Creating a Client-Side Vault (Using Cryptomator)

The following steps utilize Cryptomator, a widely accepted open-source E2EE client, as a blueprint for implementing zero-knowledge synchronization.

Step 1: Download and Installation

Action: Download and install the Cryptomator client corresponding to the operating system in use.

Step 2: Vault Creation and Key Definition

Action: Create a new vault and select a location inside the folder managed by the existing cloud sync client (e.g., ~/GoogleDrive/Vault_Alpha). Action: Establish a strong, unique passphrase. Cryptomator automatically handles the complexity of key derivation, utilizing the memory-intensive Scrypt function to securely derive the KEK, which protects the internal master keys. Warning: Using a passphrase already known to an attacker or used on another system severely compromises the vault’s security.

Step 3: Linking and Unlocking the Vault

Action: Unlock the newly created vault. The client application creates a secure virtual drive or mounting point on the local file system (e.g., a mounted disk or drive letter like V: on Windows). This mounted location is the only place where the plaintext files should be manipulated.

Step 4: Uploading the First File and Syncing

Action: Drag a sensitive file (e.g., BoardMeetingMinutes.docx) into the mounted virtual drive (V:). The Cryptomator client performs the encryption and filename obfuscation locally. Action: The cloud sync client (Dropbox, OneDrive) then recognizes the resulting encrypted files (e.g., the directory structure files and the content files ending in .c9r) and uploads this scrambled ciphertext to the remote cloud server. Verify: The cloud provider never sees the file name or content in plaintext.

Proof of Work Block 1: Verification

The implementation of E2EE requires confirmation of specific cryptographic settings to validate its security posture.

- Settings Snapshot: A secure E2EE vault must use AES-256 GCM for content encryption. Key derivation must utilize Scrypt (non-parallel) to stretch the user password effectively. The wrapping of the internal master keys should adhere to established standards, such as AES Key Wrap (RFC 3394).

- Verification Check: Action: To confirm that E2EE is functioning correctly, access the cloud provider’s web interface (e.g., Dropbox.com). Verify: Navigate to the vault folder. The verification succeeds if all file names are replaced by randomized identifiers, and the folder structure is represented by encrypted directory files (e.g.,

dfiles) and the configuration file (masterkey.cryptomator). The original, readable file name (BoardMeetingMinutes.docx) must not be visible on the server interface.

The Sharing Challenge: Key Exchange and Collaboration

E2EE fundamentally redesigns collaboration models, eliminating the convenience features built into SSE-based cloud platforms. Since the server cannot read the data, it cannot facilitate sharing mechanisms that depend on server-side decryption.

Why Standard Sharing Links Fail

Cloud services commonly offer features such as “share with anyone with the link” or real-time document collaboration. These capabilities necessitate that the provider (e.g., Apple for iWork, Dropbox for Paper) has access to the encryption keys to decrypt the content temporarily. This server-side action instantly violates the zero-knowledge guarantee of E2EE.

If a file must maintain strict E2EE protection, sharing via automated cloud links is impossible. The recipient must possess the decryption key (or password) for the vault to access the files, which must be shared securely outside the channel provided by the untrusted cloud vendor.

Key Distribution Strategies: The “Out-of-Band” Requirement

To share an E2EE vault with a colleague or spouse, the vault password must be communicated using a channel that is entirely separate and trustworthy, an out-of-band communication.

- Secure Methods: The master password should be communicated via an established, secure, E2EE platform (such as Signal or encrypted email) or exchanged physically in person. Never transmit the key material via standard, unencrypted channels, or through the same potentially untrusted cloud service that hosts the encrypted data.

- The Trust Burden: Sharing the vault password fundamentally extends the security perimeter to the collaborator’s device and their key management practices. Organizational security depends entirely on the trusted recipient maintaining strong operational security and handling the key material with utmost care.

Managed E2EE Sharing: Specialized Solutions

Certain high-level E2EE synchronization solutions attempt to streamline the sharing process while retaining the zero-knowledge principle. For example, specialized offerings like Cryptomator Hub manage access by using advanced key exchange protocols such as Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman Ephemeral Static (ECDH-ES).

In this managed model, the Hub instance manages cryptographic access tokens (JWE ciphertexts) tied to individual user keys. When a user needs access, they authenticate to the Hub, retrieve their personalized token, and use their local, static private key to decrypt the token, which contains the vault’s raw master key. This allows an administrator to grant or revoke access for a specific user without ever knowing or sharing the master vault password, providing an essential feature for corporate environments that require user lifecycle management.

Proof of Work Block 2: Secure Sharing Example

- Objective: Securely share access to a high-value E2EE vault (Vault Gamma) with a new team member, Ben.

- Action: The administrator, Alice, uses AWS Wickr, a secure messaging platform built on 256-bit E2EE, to transmit the complex 32-character Vault Gamma passphrase to Ben.

- Safety Measure: Alice configures the Wickr message to automatically expire and be destroyed from Ben’s device after 48 hours. This ensures the key material’s persistence is minimized outside of Ben’s secure password manager, mitigating the risk if Ben’s messaging logs were later compromised.

Troubleshooting E2EE Sync Failures (The Technician’s Guide)

E2EE sync solutions are significantly more challenging to troubleshoot than traditional cloud sync. Because the cloud provider cannot decrypt the data or see the file structure, they cannot assist in resolving conflicts or corruption. Responsibility for maintaining data integrity and resolving errors rests solely with the user and the client application.

Symptom and Fix Matrix

The most frequent operational failures in E2EE sync environments revolve around synchronization conflicts and corruption of the client’s local database, often triggered by major software updates or the introduction of convenience features.

Table III: Troubleshooting E2EE Sync Errors

| Symptom / Error String | Root Cause(s) | Non-Destructive Fix |

| Client sync database corrupted | Virtual File System (VFS) enabled; uploading files to a previously unencrypted folder; conflicting internal permission settings. | Action: Disable VFS features; for Nextcloud, manually check Advanced Security Settings for redundant/denied User permissions and delete them; force a full client refresh. |

File uploaded twice with conflict suffix (e.g., ...c9r (Created by Alice)) |

Concurrent editing across multiple synced devices before sync completion; cloud client creates a version conflict on the encrypted name. | Action: Pause sync; manually compare versions using the decrypted vault; delete the losing encrypted file; rename the winning encrypted file to remove the conflict stamp. |

| Client refuses to upload file to E2EE folder | Client software bug or version protocol mismatch. | Action: Downgrade the client application to a stable version known to support E2EE (e.g., Nextcloud users previously resolved upload issues by downgrading to v3.13.4 after v3.14.0 release). |

| Inability to decrypt data after changing devices | Key derivation parameters mismatch; incorrect keyboard layout or special characters used during master key entry. | Action: Confirm the exact keyboard layout used for vault creation; attempt decryption on the original creation device; verify KDF parameters (Scrypt cost factors) are consistent. |

Root Causes of Sync Database Corruption

Client sync database corruption is a high-impact failure that requires immediate intervention. The primary causes are often linked to architectural conflicts within the sync software.

- VFS Interference: Modern sync clients often implement Virtual File Systems (VFS) to save local disk space by streaming files on demand. This feature frequently conflicts with the E2EE mechanism, which requires cryptographic integrity checks and full local processing, leading to sync crashes and database corruption.

- Permission Overlap: In environments like Nextcloud, enabling E2EE can introduce conflicting permission entries in the server’s security settings. If the client encounters redundant or conflicting permissions (e.g., a “Users” permission group with special “Deny” settings), the sync process can halt and report a corrupted database, requiring manual administrative cleanup.

- Client Version Instability: E2EE functionality is exceptionally sensitive to client application updates. The development of E2EE is often complex, and seemingly minor client updates can introduce critical bugs that break fundamental features, such as the ability to upload files to an E2EE folder. Users maintaining strict E2EE environments may be forced to halt updates or revert to known-good client versions until stability is confirmed.

Non-Destructive Conflict Resolution

Sync conflicts manifest as two or more versions of the encrypted file residing in the cloud folder. These conflicts occur on the obfuscated filename, which is managed by the sync client.

- Stop Synchronization: The first critical action is to immediately pause the cloud synchronization application (Dropbox, Google Drive, Nextcloud client) to prevent the creation of further conflicts.

- Locate and Review: Unlock the E2EE vault locally to view the conflicting plaintext files. These files will often carry a sync conflict stamp (e.g., appended device name or timestamp). Review the contents and modification dates to determine which version is correct.

- Identify and Delete the Loser: Once the winning file is chosen, delete the corresponding encrypted file (the “loser”) from the underlying cloud sync folder.

- Rename the Winner: Locate the winning encrypted file and manually rename it, carefully removing the sync conflict stamp appended by the cloud client. The remaining filename must exactly match the expected obfuscated name structure defined by the E2EE client (e.g.,

...c9r). - Restart Sync: Resume synchronization. The client will recognize the single, correctly named encrypted file as the current version, resolving the conflict without data loss.

Last Resort: Addressing Catastrophic Master Key Loss

E2EE provides an absolute guarantee of privacy, but this comes with an absolute operational risk: irreversible data loss if the master key is lost. Since the cloud vendor never possessed the cryptographic key derivation material, they possess zero ability to rescue the data, regardless of the severity of the loss or the urgency of the need. This situation contrasts sharply with SSE, where vendors often maintain complex key recovery mechanisms via KMS access. For E2EE users, prevention—through meticulous, redundant key storage—is the only viable strategy.

Final Verdict: Choosing the Right Protection Level

The decision between E2EE and SSE must be a strategic choice based on the organization’s trust model, its regulatory requirements (such as data sovereignty mandates), and its capacity to manage technical complexity. The primary friction in E2EE is the required sacrifice of convenience and vendor support in favor of cryptographic certainty.

Use-Case Chooser Table

| Persona | Primary Goal | Recommended Encryption | Trade-Off/Justification |

| Corporate Admin | Centralized management, internal search, legal compliance access. | Encrypted At Rest (SSE-KMS) | Prioritizes key recoverability and vendor capability to assist with compliance and system indexing. |

| Freelancer/Journalist | Absolute source confidentiality, protection against mass surveillance. | E2EE Sync (CSE) | Prioritizes zero-knowledge principle; accepts high operational risk for data protection against the host. |

| Research Team (Sensitive Data) | Data sovereignty, restricted cryptographic boundaries. | E2EE Sync (CSE) | Requires strict control over the key lifecycle to adhere to specific ethical or regulatory standards. |

| Casual User | Convenience, simplicity, basic data protection. | Encrypted At Rest (SSE) | Default AES-256 protection is often sufficient; benefits from easy sharing/recovery options. |

When You Should Not Use E2EE

E2EE is an inappropriate choice when core workflow requirements necessitate interaction with the server’s processing capabilities. Professionals should avoid implementing E2EE if their operations critically depend on any of the following factors:

- Real-time Collaboration: Workflows requiring multiple users to edit a single document simultaneously via the cloud provider’s native web-based editors (e.g., Google Docs, Office 365).

- Web Previews and Search: Dependence on the cloud provider’s web interface for file previews, content indexing, or search functionality, which requires server-side decryption.

- Vendor-Assisted Recovery: If the organization cannot tolerate the risk of complete and irreversible data loss resulting from misplaced or forgotten passwords, E2EE introduces an unacceptable level of operational risk.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Does using Customer Managed Keys (CMK) provide End-to-End Encryption?

A: No. CMKs transfer the management of the key’s rotation and deletion to the customer, but the key material remains within the vendor’s highly secured KMS infrastructure. The vendor’s infrastructure still executes the decryption when necessary, failing to achieve the zero-knowledge standard.

Q: Can I use E2EE with large datasets like high-resolution research archives?

A: Yes. Modern E2EE clients use envelope encryption, where a fast symmetric Data Encryption Key (DEK) encrypts the large content. The DEK itself is then quickly secured by the Key Encryption Key (KEK) derived from your password, making the process efficient for large files.

Q: If I lose my E2EE password, can the cloud provider recover my data?

A: No, recovery is cryptographically impossible. Since the provider never receives the decryption key or the key derivation parameters (like the Scrypt salt and cost factors), they possess only scrambled ciphertext and cannot decrypt the data for anyone.

Q: Why is Scrypt preferred over other Key Derivation Functions?

A: Scrypt is favored because it is designed to be highly memory-intensive, in addition to being computationally expensive. This design specifically defends against parallel brute-force attacks using GPUs or specialized mining hardware, offering a stronger defense layer against password guessing than older KDFs.

Q: Does E2EE protect my data from subpoenas or government requests?

A: Yes. E2EE provides substantial protection against mass surveillance and data requests because the service provider can only furnish encrypted, unreadable files. Security experts and activists advocate for E2EE specifically because the provider lacks the cryptographic means to comply with requests for plaintext content.

Q: What are the main challenges when sharing an E2EE vault?

A: The main challenge is the necessity of securely transmitting the decryption key or password to the recipient using a trusted out-of-band communication channel. Additionally, all collaborators must maintain strict operational vigilance, as conflict resolution must be handled manually between endpoints.

Q: Does the cloud provider know when I access my E2EE files?

A: Yes. The cloud provider logs the timestamp and your originating IP address whenever you access or modify the encrypted file container (e.g., the .c9r file). While they know sync activity occurred, they remain ignorant of the plaintext file name, folder structure, or actual content being accessed.

Q: Can I use both SSE and E2EE simultaneously?

A: Yes, it is possible. If data is encrypted client-side (E2EE), the server will apply its standard Server-Side Encryption (SSE) to the already-scrambled data. This double encryption is redundant and adds minor overhead without improving security, as the zero-knowledge assurance of E2EE remains the strongest element in the security chain.

Q: Why do E2EE clients fail after software updates (e.g., Nextcloud)?

A: E2EE relies on delicate client-server protocols and local database integrity. Updates can introduce architectural changes, such as new VFS implementations, that conflict with the client’s local E2EE state, causing synchronization failures and database corruption. This often requires users to pin to specific, known-stable client versions.

Q: How secure is Cryptomator’s filename obfuscation?

A: Cryptomator’s filename obfuscation is highly secure. It cryptographically encrypts both the filename and directory structure, preventing external parties from performing behavioral analysis based on file identifiers or path names. The server only receives randomized, unintelligible identifiers, defeating passive metadata surveillance.

Final Verdict: Choosing the Right Protection Level

The decision between E2EE and SSE must be a strategic choice based on the organization’s trust model, its regulatory requirements (such as data sovereignty mandates), and its capacity to manage technical complexity. The primary friction in E2EE is the required sacrifice of convenience and vendor support in favor of cryptographic certainty.

The final verdict is that the only true path to data sovereignty is End-to-End Encryption (E2EE). While standard SSE offers convenience and vendor-assisted recovery, E2EE provides cryptographic proof that the service provider cannot access the plaintext, eliminating metadata leakage and minimizing legal risk. Organizations must select the model that aligns with their risk tolerance for insider threats and their ability to manage complex key lifecycles.

The analysis confirms the need for two distinct strategies: use SSE-KMS for enterprise recovery and compliance auditing, and E2EE (Client-Side Encryption) for all highly sensitive data requiring absolute confidentiality and zero-knowledge assurance.