An In Depth Security Analysis of Archive Encryption: 7 Zip Versus WinRAR Versus WinZip

File archivers offer an essential security control: data encryption. This report provides a definitive, evidence based analysis of 7-Zip, WinRAR, and WinZip, evaluating their encryption schemes against three core technical pillars the cipher, the key derivation function, and metadata protection to illuminate crucial security differences and guide professionals to the strongest choice.

I. Introduction: Beyond Compression, The Critical Role of Encryption in File Archives

File archivers such as 7-Zip, WinRAR, and WinZip are ubiquitous utilities, integral to digital workflows for bundling files and reducing storage footprints. Their primary function, data compression, is well understood and widely utilized. However, these applications also offer a critical secondary function: data encryption. In an era of heightened digital privacy concerns and pervasive data breach threats, the ability to secure archived data with a password has transitioned from a niche feature to an essential security control.

While all three of these leading archivers market their encryption capabilities, often highlighting the use of strong cryptographic standards, a dangerous assumption of equivalent security has become prevalent among users. The reality is far more nuanced. The actual level of protection afforded by an encrypted archive is not determined by a single feature but by a chain of cryptographic components, and the strength of this chain is dictated by its weakest link. A superficial understanding, often based on marketing claims, can lead to a false sense of security, with potentially severe consequences for data confidentiality.

To move beyond surface level comparisons, a rigorous security analysis must be framed around three core technical pillars. These pillars collectively determine the true resilience of an encrypted archive against a dedicated adversary:

- The Core Cipher (AES-256): This is the fundamental cryptographic algorithm responsible for scrambling the raw file content, rendering it unreadable without the correct key. Its strength is the bedrock of the entire security model.

- The Key Derivation Function (KDF): This is the crucial, and often overlooked, process that transforms a user’s relatively simple, human memorable password into a complex, high entropy cryptographic key. The robustness of the KDF is the primary defense against offline brute force and dictionary attacks aimed at guessing the password.

- Metadata Protection (Header Encryption): This refers to the capability to encrypt not only the data within the files but also the metadata associated with them, such as filenames, folder structures, file sizes, and timestamps. In many contexts, this metadata can be as sensitive as the content itself.

This report provides a definitive, evidence based analysis of 7-Zip, WinRAR, and WinZip, evaluating their encryption schemes against these three foundational pillars. By deconstructing their respective implementations and comparing them to modern cryptographic best practices, this analysis aims to equip security professionals, IT administrators, and privacy conscious users with the technical insight required to make informed decisions that align with their specific threat models and security requirements.

II. The Core Cipher: A Comparative Look at AES 256 Implementations

The foundation of any modern encryption system is its core cryptographic cipher. In this regard, 7-Zip, WinRAR, and WinZip have all converged on the same industry leading standard for their most secure offerings: the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) with a 256-bit key length.

The Industry Standard: AES 256

AES is a symmetric key block cipher adopted by the U.S. government and used worldwide to protect classified information. The “256” denotes the length of the cryptographic key in bits. The number of possible keys for AES-256 is $2^{256}$, an astronomically large number that renders a brute force attack computationally infeasible with any current or foreseeable technology. For this reason, AES-256 is universally regarded as the gold standard for symmetric data encryption at rest.

The universal adoption of AES-256 across these three archivers creates a baseline of strong cryptographic potential. However, this apparent parity can be misleading. While the core algorithm is robust, its security in practice depends heavily on the surrounding implementation, particularly the block cipher mode of operation.

Modes of Operation

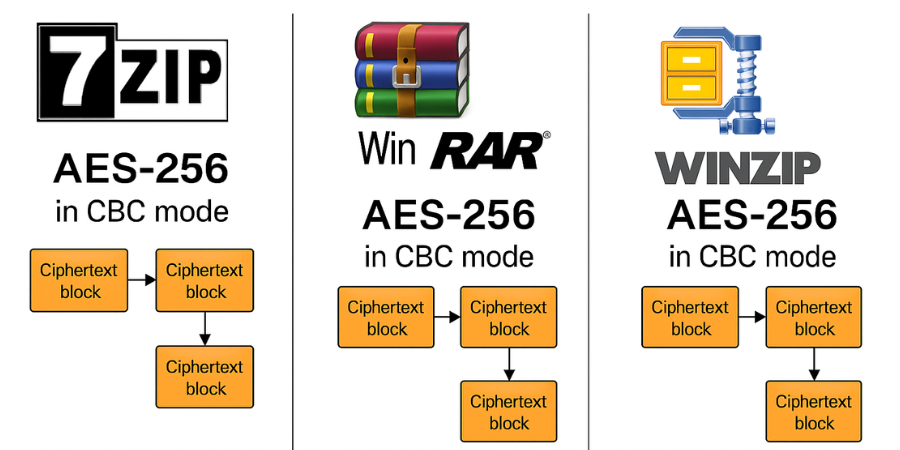

A block cipher mode of operation is an algorithm that specifies how to repeatedly and securely apply a block cipher (like AES) to encrypt amounts of data larger than a single block. All three archivers utilize well established modes for this purpose.

- WinRAR (RAR 5.0): The modern RAR 5.0 format employs AES-256 in Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) mode. In CBC mode, each block of plaintext is XORed with the previous ciphertext block before being encrypted.

- 7-Zip (.7z format): The native 7z archive format also uses AES-256 in CBC mode, providing the same essential security properties as WinRAR’s implementation.

- WinZip (.zipx format): WinZip’s AES implementation, which has become a de facto standard for encrypted ZIP files, also functions in a manner consistent with CBC mode.

The use of standard, well vetted modes like CBC across all three platforms means that, from a purely algorithmic perspective, the core content encryption is sound.

The Negligible Impact of Hardware Acceleration

A common concern with strong encryption is its potential performance overhead. However, modern CPUs from both Intel and AMD incorporate the AES instruction set (AES-NI). This hardware level acceleration offloads the computationally intensive steps of the AES algorithm directly to the processor, resulting in a dramatic increase in encryption and decryption speeds. On a contemporary system, the performance impact of on the fly AES-256 encryption is often so minimal that it is limited by the read/write speed of the storage device rather than the CPU’s ability to perform cryptographic operations. This technological advancement has effectively eliminated the trade off between speed and the security of the core cipher.

The Illusion of Parity

The consistent use of “AES-256” in marketing materials and user interfaces for 7-Zip, WinRAR, and WinZip has cultivated a widespread and dangerous illusion of equivalent security. A non expert user, recognizing AES-256 as a trusted standard, may logically but incorrectly conclude that the protection offered by all three is identical. This conclusion is fundamentally flawed.

The strength of a password protected encryption system is not solely defined by its final cipher. An attacker does not target the AES-256 algorithm itself; they target the weakest point in the implementation, the user’s password. The true battleground for security lies in how that password is transformed into the AES key and how much of the archive’s metadata is left exposed. The vast differences in the Key Derivation Functions and header encryption capabilities of these tools, as will be detailed in the subsequent sections, reveal that the core cipher’s strength is merely a prerequisite for security, not a guarantee of it. The most critical vulnerabilities and differentiating factors are found not in the well known cipher, but in the less publicized details of its implementation.

III. The First Line of Defense: Deconstructing Key Derivation Function (KDF) Robustness

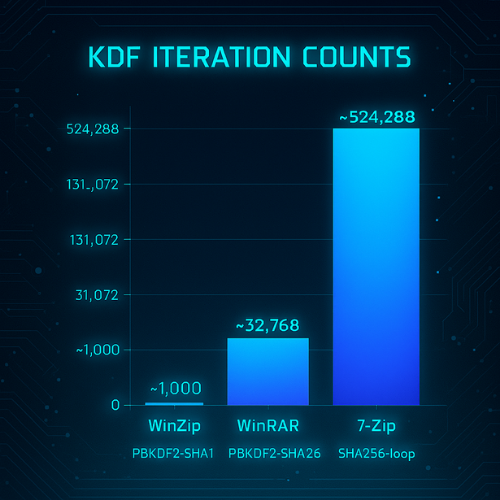

While AES-256 provides the cryptographic muscle, the Key Derivation Function (KDF) serves as the gatekeeper. Its function is to take a user supplied password, which is typically low in entropy and susceptible to guessing, and “stretch” it through a computationally intensive process to produce a strong, high entropy cryptographic key. The primary security role of a KDF is to dramatically increase the time and cost for an attacker to test a single password guess. The effectiveness of a KDF is largely measured by its algorithm and, most critically, its iteration count. It is in this domain that the security postures of 7-Zip, WinRAR, and WinZip diverge most dramatically.

WinZip’s KDF: A Critically Outdated Implementation

WinZip’s implementation of AES encryption relies on the Password Based Key Derivation Function 2 (PBKDF2). While PBKDF2 is a recognized standard, WinZip’s specific configuration is alarmingly weak by modern standards.

- Technical Specification: WinZip uses PBKDF2 with HMAC-SHA-1 as its underlying pseudorandom function.

- Critical Flaw: The most significant vulnerability in WinZip’s scheme is its fixed and exceptionally low iteration count of only 1,000.

This iteration count is a relic of a bygone era in computing. Modern security guidelines from organizations like the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) recommend an iteration count of 600,000 or more for PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256. This means WinZip’s KDF is over 600 times weaker than current recommendations. Against a modern password cracking rig equipped with high end GPUs, a 1,000 iteration KDF can be processed at a rate of millions or even billions of guesses per second, making it only marginally more difficult to crack than a simple, unsalted hash. Consequently, WinZip’s KDF should be considered broken for any serious security application.

WinRAR’s KDF: A Substantial but Incomplete Improvement

WinRAR, with its modern RAR 5.0 archive format, represents a significant step forward in KDF security compared to WinZip.

- Technical Specification: The RAR 5.0 format utilizes PBKDF2 with the much stronger HMAC-SHA256 hash algorithm.

- Iteration Count: Analysis reveals a default iteration count of 32,768 iterations.

An iteration count of 32,768 makes a brute force attack over 32 times more difficult than against a WinZip archive. This is a substantial improvement that moves WinRAR’s security into a more respectable category. However, this count still falls considerably short of the hundreds of thousands of iterations recommended by security bodies and implemented by 7-Zip. This design choice appears to be a deliberate trade off, balancing enhanced security against the desire for faster archive opening times.

7-Zip’s KDF: A High Iteration, CPU Centric Approach

7-Zip, in its native .7z format, employs a custom KDF that prioritizes a high iteration count to maximize brute force resistance.

-

Technical Specification: The .7z format uses a key derivation function based on a loop that repeatedly hashes the user’s password and a salt value using the SHA-256 algorithm.

- Iteration Count: The number of SHA-256 rounds is fixed at an impressively high 524,288 ($2^{19}$).

This high iteration count places 7-Zip’s brute force resistance far ahead of both WinZip and WinRAR’s default setting. It aligns closely with modern security recommendations and provides a formidable defense against password guessing attacks. The 7-Zip developer has publicly justified the design choice, arguing that the sub one second key derivation time on modern CPUs strikes a good balance.

KDF Strength as a Reflection of Security Philosophy

The profound differences in these KDF implementations are not merely technical minutiae, they are direct reflections of each developer’s underlying security philosophy.

- WinZip’s Philosophy: Legacy and Convenience. The 1,000 iteration KDF is indicative of a design philosophy rooted in legacy compatibility and providing “checkbox security.”

- WinRAR’s Philosophy: Balanced Pragmatism. The move to a $\sim 32,768$ iteration PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256 reflects a pragmatic balance. The goal is to offer “good enough” security for the vast majority of users without introducing a noticeable delay when opening archives.

- 7-Zip’s Philosophy: Security and Transparency. The choice of a 524,288 iteration loop signals a “security first” mindset. The developer has prioritized making brute force attacks as difficult as possible, accepting a minor performance trade off for a major security gain.

IV. Beyond Content: The Security Implications of Header and Metadata Encryption

While strong encryption of file content is essential, it addresses only part of the confidentiality problem. An archive’s metadata, which includes filenames, folder names, file sizes, and modification timestamps, can itself be highly sensitive. The leakage of this information can reveal the nature of a project or the context of confidential business activities, even if the file contents remain unreadable. Therefore, the ability to encrypt the archive’s header, which contains this metadata, is a critical feature for comprehensive security.

WinRAR’s Comprehensive Protection

WinRAR provides a clear and effective solution for metadata protection through its “Encrypt file names” option, available when creating an archive. When this feature is enabled, WinRAR encrypts not only the file data but also all other sensitive archive areas, including filenames, sizes, attributes, and comments. This functionality ensures that an adversary cannot draw any conclusions about the contents of the archive, providing a much higher level of confidentiality and privacy.

7-Zip’s Duality: The .7z Versus .zip Divide

7-Zip’s approach to header encryption is powerful but presents a significant potential pitfall depending on the archive format chosen by the user.

- Native .7z Format: When creating an archive in its native .7z format, 7-Zip offers a robust “Encrypt file names” option. Similar to WinRAR, this feature encrypts the archive’s central directory, effectively hiding all filenames and the folder structure from anyone without the password. This makes the .7z format a strong choice for high security applications.

- Compatible .zip Format: In a concession to compatibility, when 7-Zip is used to create a standard .zip file, the option to encrypt filenames is not available. Even if the user selects AES-256 encryption for the file contents, the archive’s header remains in plaintext.

WinZip’s Deficiency: A Critical Security Gap

WinZip’s implementation of ZIP encryption suffers from a critical and fundamental security flaw: it offers no mechanism to encrypt filenames or the directory structure. The list of files within a WinZip encrypted archive is always visible to anyone who possesses the file, regardless of whether they have the password.

This complete lack of native header encryption renders WinZip unsuitable for any scenario where the names of files or folders are considered sensitive information.

Compatibility as a Security Anti Pattern

The divergent approaches to header encryption are a direct consequence of each developer’s strategic decision regarding backward compatibility versus modern security.

- The Legacy of ZIP: The original ZIP format and its weak, proprietary ZipCrypto encryption scheme did not include a standard for encrypting the archive’s central directory (the file list).

- WinZip’s Adherence to Tradition: As the historical standard bearer for the ZIP format, WinZip’s design philosophy prioritizes maximum compatibility. Its failure to implement filename encryption is a deliberate choice to ensure that its archives can be opened and listed by the widest possible range of utilities, at the direct expense of user privacy.

- 7-Zip’s Dual Approach: 7-Zip’s strategy explicitly demonstrates this conflict. For its proprietary .7z format, unburdened by legacy constraints, it implemented a robust header encryption feature. When creating .zip files, it reverts to the format’s limitations and omits this feature, sacrificing security for compatibility.

-

WinRAR’s Proprietary Advantage: By leveraging its own proprietary RAR format, WinRAR’s developers were never bound by the limitations of the ZIP standard. This freedom allowed them to design the RAR 5.0 format with modern security principles from the outset, incorporating strong header encryption as a core, optional feature.

V. Holistic Security Posture: A Comparative Synthesis and Threat Model Analysis

A comprehensive security assessment requires synthesizing the individual components into a holistic view of each tool’s overall defensive posture. The following table provides a direct, at a glance comparison of the key security differentiators.

Consolidated Security Analysis

| Feature | 7-Zip (.7z format) | WinRAR (RAR 5.0 format) | WinZip (.zipx format) |

| Core Cipher | AES-256 (CBC mode) | AES-256 (CBC mode) | AES-256 |

| KDF Algorithm | Custom (SHA-256 based) | PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256 | PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA-1 |

| KDF Iterations | $\sim 524,288$ ($2^{19}$) | $\sim 32,768$ ($2^{15}$) | $1,000$ |

| Header/Filename Encryption | Yes (Optional) | Yes (Optional) | No |

| Source Model | Open Source | Closed Source | Closed Source |

| Overall Brute Force Resistance | Very High | High | Very Low |

| Metadata Privacy | Very High | Very High | None |

Threat Model Evaluation

The practical significance of these differences is best understood by evaluating each tool against specific threat models.

-

The Casual Adversary: This adversary is not expected to employ specialized tools. Any of the three tools, when used with a password, will suffice to prevent casual snooping.

- The Opportunistic Attacker: This attacker may use publicly available password cracking software. In this scenario, the robustness of the KDF is paramount.

- WinZip: Fails this test. Its 1,000 iteration KDF provides negligible resistance to GPU based cracking tools.

- WinRAR: Offers a good level of protection. Its $\sim 32,768$ iterations present a significant computational barrier.

- 7-Zip: Provides excellent protection. Its 524,288 iterations make an offline brute force attack extremely time consuming and costly, offering the highest level of security against this threat.

-

The Targeted Attacker/Eavesdropper: This model involves a sophisticated adversary who may intercept files or gain access to cloud storage.

- WinZip: Is completely unsuitable. Its weak KDF and total lack of header encryption mean that an attacker can easily crack weak passwords and immediately see the names and structure of all contained files.

-

WinRAR and 7-Zip (.7z format): These are the only viable options. Both offer strong KDFs to resist brute force attacks and, crucially, provide the option to encrypt filenames and directory structures.

VI. Recommendations and Conclusion

The detailed technical analysis reveals significant disparities in security implementations. The choice of which tool to use should be based on a careful consideration of the user’s specific security requirements and threat model.

Evidence Based Recommendations

- For Maximum Security and Privacy: 7-Zip, used exclusively with its native .7z format and with the “Encrypt file names” option enabled, is the recommended choice. This configuration provides the strongest defense against brute force password attacks due to its high iteration KDF (524,288 rounds of SHA-256) and ensures complete metadata privacy by encrypting the archive header. Furthermore, its open source nature allows for public scrutiny of its code, providing a higher degree of transparency and trust.

- For Strong Security with a Polished User Experience: WinRAR, using the modern RAR 5.0 format with the “Encrypt file names” option enabled, is a highly recommended alternative. While its default KDF iteration count ($\sim 32,768$) is lower than 7-Zip’s, it is still substantially more secure than WinZip and offers robust protection against all but the most dedicated adversaries.

- When to Avoid WinZip for Security: It is strongly recommended to avoid using WinZip for any purpose where data security or confidentiality is a genuine concern. Its critically weak KDF (1,000 iterations of PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA-1) and complete lack of metadata protection are disqualifying flaws from a modern security perspective.

The Overarching Importance of Password Hygiene

It must be emphasized that the security of any of these tools is ultimately anchored to the strength of the user’s chosen password. A strong KDF can make a brute force attack on a complex password infeasible, but it cannot protect a weak, common, or easily guessable password from a dictionary attack. Users must adhere to best practices for creating passphrases:

- Length: Prioritize length over complexity. A passphrase of several random words is typically stronger and more memorable than a short, complex string of characters.

- Uniqueness: The password used for an archive should be unique and not reused from any other account or service.

- Entropy: Avoid dictionary words, common phrases, names, dates, or predictable patterns.

Concluding Summary

In conclusion, the claim of “AES-256 encryption” is not a monolithic guarantee of security. A deep analysis of the cryptographic implementations within 7-Zip, WinRAR, and WinZip reveals a clear security hierarchy. 7-Zip’s native .7z format stands at the top, offering exceptional brute force resistance and complete metadata privacy within a transparent, open source framework. WinRAR’s modern RAR 5.0 format follows closely, providing a robust and user friendly solution. WinZip, constrained by its adherence to legacy standards, lags significantly behind, offering a level of protection that is inadequate against modern threats. The ultimate security of an encrypted archive rests not on the brand name of the tool used to create it, but on the technical rigor of its implementation and the strength of the password chosen by the user.