Selecting the Right Cloud Encryption Model: SSE, CSE, and Zero Knowledge Explained

This executive overview, presented by Newsoftwares.net, details the three critical models for cloud encryption. Choosing a cloud encryption method is a critical security decision, not just a box to check. The right choice depends entirely on who you need to keep out of your data: external hackers, or the cloud provider itself. By defining the key holder, this guide clarifies the security posture, costs, and compliance risks of Server, Side Encryption (SSE), Client, Side Encryption (CSE), and the superior data privacy of Zero, Knowledge Encryption (ZKE), ensuring informed and convenient data security decisions.

Choosing a cloud encryption method is a critical security decision, not just a box to check. The right choice depends entirely on who you need to keep out of your data: external hackers, or the cloud provider itself.

Choosing Your Cloud Encryption Model Summary

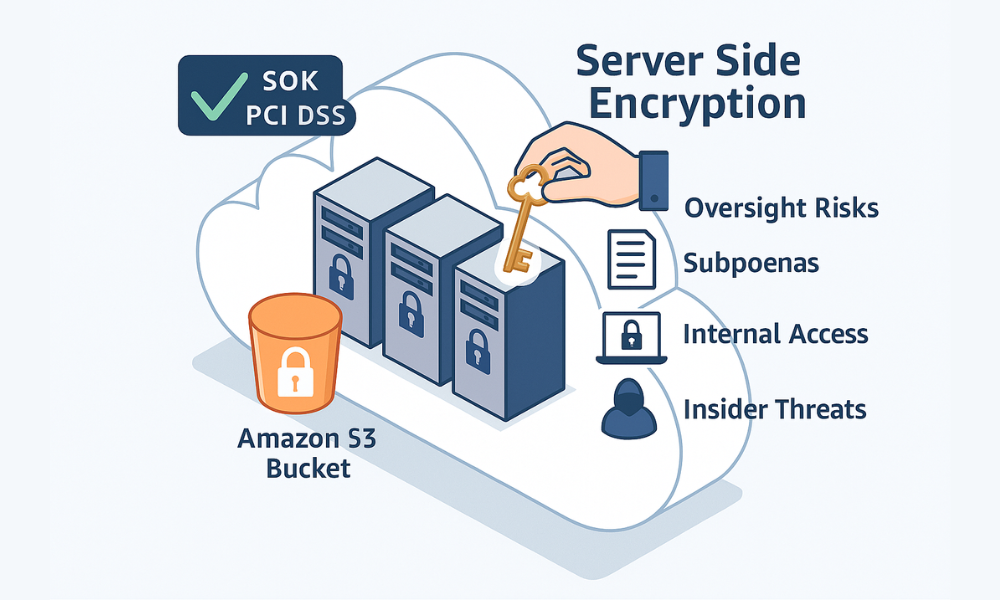

- For compliance and auditable access control (SOX, PCI DSS): Use Server, Side Encryption with Customer, Managed Keys (SSE-KMS or CMEK). This grants you granular control over key policies and tracks every access attempt to the encryption key.

- For maximum data sovereignty and technical defense against provider insiders: Choose Zero, Knowledge Encryption (ZKE). The keys never leave the client device, making it technically impossible for the cloud host to decrypt your files.

- For convenience and automatic baseline security (non, critical data): Rely on Default Server, Side Encryption (SSE-S3). Data is automatically encrypted at rest, fulfilling basic mandates, but the provider retains full control over the keys.

The Core Problem: Why Key Ownership Determines Security

Most users believe their data is secure simply because the cloud provider guarantees it is “encrypted.” This assumption often ignores the fundamental reality of key ownership. Encryption is only effective if the key is held by the correct party.

The Control Paradox: Why “Encrypted” Is Not “Private”

Major cloud platforms automatically apply encryption to stored data. For example, Amazon S3 applies Server, Side Encryption with S3 managed keys (SSE-S3) as the default level of encryption for every bucket. This process encrypts the data at the object level as it is written to the disks in the AWS data centers.

This protection is essential. It protects data against scenarios like physical theft of servers or unauthorized external network intrusion. However, this level of security only satisfies the requirement for “data at rest” encryption. In the SSE-S3 model, the cloud provider completely manages and controls the encryption keys.

This configuration introduces a trust requirement. Because the service provider holds the keys, they can decrypt the data whenever necessary. This means they can be forced to access the data due to legal or governmental requests (such as subpoenas). Furthermore, any successful internal compromise of the provider’s key management systems, or malicious actions by the provider’s own infrastructure staff (insider threats), gives them potential access to sensitive customer information. For organizations handling high, sensitivity data, intellectual property, trade secrets, or protected health information (PHI), default SSE requires a level of trust in the provider’s employees and processes that is often deemed an unacceptable operational risk.

Understanding the Three Pillars of Cloud Data Protection

Cloud data protection models are best defined by the physical location where the key is managed and where the data decryption process occurs. The three primary models represent a gradient of control, moving the cryptographic process closer to the user.

- Server, Side Encryption (SSE): The encryption and decryption happen entirely on the cloud server after the data is uploaded. The cloud provider holds the encryption key, either managing it entirely or managing the infrastructure that hosts the customer’s key.

- Client, Side Encryption (CSE): The encryption happens on the user’s device (the client) before the data is transmitted to the cloud. However, in many enterprise implementations of CSE, the key itself is still managed centrally via an external Key Management Service (KMS).

- Zero, Knowledge Encryption (ZKE): This is the most secure form of client, side encryption. The key is generated locally, derived from the user’s local password, and never leaves the client device or its memory. The service provider receives and stores only scrambled ciphertext.

Server, Side Encryption (SSE): Convenience and Compliance Baseline

SSE represents the set of encryption methods managed by the cloud provider. While convenient, it varies significantly in the level of control it grants the customer.

SSE-S3: Provider Keys and Default Security

SSE-S3 is the base encryption layer for platforms like Amazon S3, using AES-256 to automatically encrypt data at rest. This setup requires zero configuration or management effort from the user. Since January 5, 2023, all new object uploads to S3 are automatically encrypted at no additional cost and with no impact on performance.

This fulfills most regulatory requirements mandating basic data at rest encryption. However, the service provider (AWS) retains full operational control over the encryption keys, meaning the user has no ability to revoke key access or monitor key usage outside of standard API logs that confirm encryption status.

SSE-KMS / Customer, Managed Encryption Keys (CMEK)

Server, Side Encryption with KMS (SSE-KMS in AWS) or Customer, Managed Encryption Keys (CMEK in GCP) elevates security by shifting key policy control to the customer. Instead of using keys managed solely by the service provider, customers provision their own keys within the provider’s Key Management Service (KMS), such as AWS KMS or GCP Cloud Key Management Service.

This method does not eliminate the provider’s technical ability to access the data, but it places a crucial, auditable layer of governance over key use. The customer defines the key policies, dictating precisely which specific IAM roles or principals can request the key for encryption or decryption.

A major benefit is auditability. Cloud Audit Logs track every request made to the key, providing clear evidence of who accessed the key and when. This is indispensable for meeting strict regulatory standards like SOX (Sarbanes, Oxley) compliance, where verifiable control and monitoring of financial data access are mandatory.

For added assurance, these customer, managed keys are frequently hosted and cryptographic operations performed within FIPS 140, 2 Level 3 validated Hardware Security Modules (HSMs). This integration ensures that the most sensitive key material is protected against physical tampering, separation the key protection from the generalized server environment. A complete security posture requires both the Key Management System (KMS) for policy control and the HSM for physical protection.

SSE-C: Customer, Supplied Keys (The Control Compromise)

Server, Side Encryption with Customer, Provided Keys (SSE-C) offers a unique middle ground. The customer generates the AES-256 encryption key and supplies it to Amazon S3 along with every upload and download request.

The process is highly controlled: Amazon S3 uses the key to encrypt the object, then immediately removes the encryption key from memory. Crucially, Amazon S3 never stores the actual encryption key. Instead, it stores a randomly salted Hash, based Message Authentication Code (HMAC) of the key, which is only used to validate future requests.

The key drawback is the immense burden of key security placed entirely on the user. If the customer loses the encryption key used for an object, the data is permanently lost. This inherent risk makes SSE-C a challenging model for large, scale enterprise data management, where key rotation and recovery mechanisms are essential.

Table 2: Key Management in Server, Side Encryption (SSE Focus)

| Model | Key Storage Location | Key Management Responsibility | Primary Customer Benefit |

| SSE-S3 (AWS Default) | AWS Managed Key Vault | Provider fully manages rotation and access | Zero management overhead, automatic baseline security |

| SSE-KMS (CMEK) | Cloud KMS (AWS KMS, GCP Cloud KMS) | Customer defines policies, provider handles infrastructure | Auditability, revocation, policy, driven access control |

| SSE-C (Customer Supplied) | Customer (Key provided per request) | Customer solely manages key generation and security | Highest level of provider non, access control within SSE |

Client, Side Encryption (CSE): Shifting Control to Your Device

Client, Side Encryption (CSE) fundamentally changes the security dynamic by moving the cryptographic operation away from the cloud infrastructure and onto the user’s local device.

CSE vs. SSE: The Location of Encryption

CSE mandates that data is encrypted on the source device (the client) before it is transmitted to the cloud storage. When the cloud storage receives the file, it is already ciphertext. Cloud providers often apply their own second layer of server, side encryption (like SSE-S3) on top of the client, encrypted data for good measure.

The main security benefit here is clear: the data is protected in transit and at rest by a key that originated on and is generally controlled by the client. The cloud provider cannot access the cleartext data simply by accessing their own key vault.

Key Management in CSE: The Centralized Key Paradox

CSE is not a monolithic concept. It can be implemented in two primary ways, leading to significant differences in final security posture:

- Local Key Management (True Zero, Knowledge): The keys are generated locally on the device, derived from a user password, and never leave the client’s control. (This is the definition of ZKE, detailed below.)

- External KMS Management (Enterprise CSE): Services like Google Workspace Client, Side Encryption (CSE) often use an external Key Management Service (KMS). While the encryption occurs on the client device (e.g., in the user’s browser), the key used for decryption is centrally managed via a KMS that the administrator controls.

This centralized key structure creates a paradox. While encryption is client, side, the external KMS is a managed service. This is excellent for centralized governance: administrators can revoke a user’s access to keys, even if the user generated the content. However, the key material still exists outside the user’s immediate device, requiring trust in the security model of the KMS vendor and the administrative control plane. This is a fundamental divergence from pure zero, knowledge models, where key material is strictly confined to the local endpoint.

The Risk Profile: Data Loss and Key Management Burden

When key control is shifted to the customer, whether through CSE or ZKE, the responsibility for safeguarding that key material is absolute.

The critical hazard is irreversible data loss. If the client, side keys are lost, the data is permanently unreadable. The encrypted objects remain stored in the cloud, and the user continues to incur storage charges until the unreadable data is manually deleted. This risk is why robust key management, including recovery keys and offsite backups of critical key material, is mandatory for any client, side encryption strategy.

Zero, Knowledge Encryption (ZKE): Maximum Privacy Achieved

Zero, Knowledge Encryption represents the gold standard for data privacy, ensuring technical separation between the user and the service provider.

Zero, Knowledge Defined: End, to, End Encryption (E2EE)

Zero, knowledge is a rigorous security model where the service provider has no means, capability, or knowledge to decrypt the user’s stored data. This is achieved through end, to, end encryption (E2EE), where data is encrypted before it leaves the device and can only be decrypted by the intended recipient using their private, local key.

The analogy is helpful: traditional cloud storage is like a safe deposit box where the bank keeps a copy of the key. ZKE is like welding your own safe shut, only you know the combination, and the bank cannot open it under any circumstance.

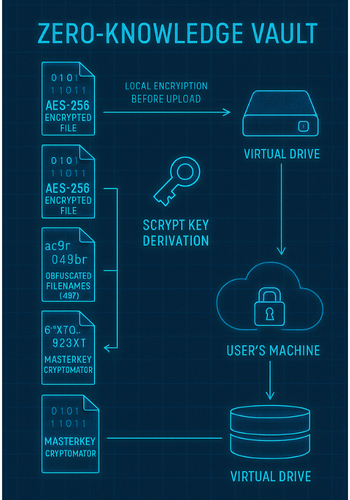

The core mechanism involves key derivation. Encryption keys are generated locally, derived from a master password (e.g., a vault password), often using a Key Derivation Function (KDF) like Scrypt. This KDF transforms the easily memorable password into a mathematically strong Key Encryption Key (KEK). This KEK is then used to encrypt the master key file (e.g., the masterkey.cryptomator file) before it is uploaded. The actual key material never leaves the user’s control.

Technical Difference: How ZKE Hides Metadata

A key technical distinction separates ZKE solutions like Cryptomator from basic file encryption tools. ZKE is designed to prevent metadata leakage. It encrypts the file contents, but also the file and folder names, and obfuscates the directory structure.

This step is critical for true privacy. If the cloud provider can still read the metadata, such as file names like tax_records_2024.pdf, they can still gain intelligence about the data’s content, purpose, and sensitivity. ZKE replaces recognizable names with unreadable, hashed strings, such as 8Jn9r1EMPB0ZIApqo1oaA8x0GymgYUI=.c9r. The provider sees only meaningless encrypted strings.

ZKE Use Cases: Protecting Highly Sensitive Data

ZKE is the mandatory choice for services built around maximal privacy, such as zero, knowledge password managers (e.g., Keeper, LastPass).

For highly regulated industries, ZKE minimizes exposure and risk. Entities handling Electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI) under HIPAA, for instance, must comply with stringent rules. When a healthcare provider (covered entity) uses a Cloud Service Provider (CSP) to store ePHI, the CSP is legally considered a Business Associate, regardless of whether they have the encryption key. A Business Associate Agreement (BAA) is required.

However, implementing ZKE ensures that the PHI is technically unreadable by the Business Associate. Although the regulatory requirements for the BAA remain, ZKE drastically reduces the actual data exposure risk and liability for the covered entity, proving the highest technical safeguard for data privacy.

The Encryption Decision Matrix: Risk, Cost, and Compliance

Selecting the appropriate encryption model requires a structured evaluation of control, risk tolerance, and compliance needs.

Insider Threat Mitigation Scorecard

Insider risk, whether accidental or malicious, poses a substantial threat to organizational security. This includes negligent exposures, such as misconfigured cloud storage, or intentional actions by authorized employees.

- ZKE: This provides the only technical control that entirely removes the threat vector posed by the cloud provider’s infrastructure staff. Because the provider never receives the key, access is a technical impossibility.

- SSE-KMS/CMEK: This mitigates insider threat through procedural control. While the key still resides in the provider’s KMS, the customer enforces strict access policies via IAM and Key Policies. The customer can maintain different KMS keys for different categories of data, ensuring that an unintentional breach of credentials grants access only to a subset of data. Furthermore, the ability to audit every key usage request acts as a strong deterrent and forensic tool.

Regulatory Alignment: Key Control for Audits

Compliance frameworks demand specific levels of control and protection:

- GDPR: The General Data Protection Regulation imposes the toughest privacy and security standards globally. GDPR compliance often requires demonstrating data sovereignty and strict control over processing. ZKE provides the highest standard for ensuring that personal data stored in the cloud remains functionally private to the owner, minimizing the risk of unauthorized processing by the cloud host.

- HIPAA: As established, ZKE minimizes data exposure risk for ePHI. However, the use of ZKE does not negate the need for a BAA between the covered entity and the CSP.

Cost and Performance Overheads

The most robust encryption methods often carry higher costs or greater operational burden.

- KMS Costs: While highly manageable and auditable, SSE-KMS and CMEK are often significantly more expensive than default SSE-S3. This is because the customer incurs costs for every single encryption or decryption request made to the KMS. To mitigate this substantial cost, particularly in high, traffic environments, users of services like AWS S3 can enable bucket, level keys. This reduces the number of requests by allowing S3 to use a single key for all objects within the bucket, rather than initiating a new KMS call for every individual object operation.

- Client, Side Performance: ZKE introduces local processing overhead. Encryption and decryption occur on the client’s CPU. This process can cause measurable latency, especially during the transfer of large files (e.g., video files over 2 GB). While the security benefits generally outweigh this minor performance hit, users with older hardware or those syncing massive datasets should be aware of the processing delay.

Table 1: Comparative Cloud Encryption Model Matrix: Control vs. Secrecy

| Feature | SSE-KMS (Managed Control) | Client-Side Encryption (CSE) | Zero-Knowledge Encryption (ZKE) |

| Key Holder/Owner | Shared Control (Policy defined by customer) | Customer (Local or External KMS) | Customer Only (Local Derivation) |

| Provider Insider Threat | Low Risk (Policy restricted, auditable) | Very Low Risk (Key is remote from cloud storage) | Zero Risk (Provider never sees the key or cleartext) |

| Metadata Exposure | High (Filenames, folder structure visible) | Moderate (File size, timestamp visible) | Minimal (Filenames, structure obfuscated) |

| Key Loss Consequence | Recoverable (Via audit logs and provider controls) | Irreversible Data Loss (Key management burden) | Irreversible Data Loss (Key management burden) |

How To Implement Zero, Knowledge Storage (Cryptomator Tutorial)

For users who require true zero, knowledge data sovereignty, client, side encryption tools are necessary. This tutorial uses Cryptomator as a leading example of ZKE implementation for common cloud storage services like Google Drive or Dropbox.

Prerequisite Check and Safety

The data security relies entirely on the strength and security of the master password and recovery key.

- Prerequisites: Ensure the target cloud folder is synchronized locally. This guide assumes a Windows operating system using the default volume type (WinFSP).

- Safety Warning: Loss of the vault password and the recovery key results in permanent data loss. Data backup outside the ZKE vault is mandatory before migrating sensitive files.

Step 1: Install and Launch Cryptomator

- Download the Cryptomator

.exeinstaller specifically designed for Windows from the official downloads page. - Launch the

.exeinstaller and follow the standard on, screen instructions. - Launch the Cryptomator application once the installation finishes.

Step 2: Create a New Vault and Define Key Strength

- Click the plus sign (+) icon in the application window. Select “Create New Vault”.

- The application prompts for a location. Navigate to and select the folder synchronized by your cloud provider (e.g., the local Google Drive folder on your PC).

- Set a strong, unique master password for the vault. Cryptomator uses this password to derive the Key Encryption Key (KEK) via the Scrypt KDF.

- Understand the cryptographic limitation: If you decide later that you need a stronger password, simply changing it will only update the KEK used to encrypt the master key file. It does not automatically re, encrypt the actual file contents. For a true upgrade in key strength, you must create a new vault and migrate the data.

Step 3: Securely Record the Recovery Key (Crucial Safety Step)

The recovery key is the only failsafe against a forgotten password or a corrupted master key file. Cryptomator does not store this recovery key on your hard drive, deriving it only when requested.

- Navigate to the “Vault Options” menu for your new vault.

- Select the “Password” tab.

- Click on “Display Recovery Key”.

- Enter the vault’s master password to derive and display the recovery key.

- Action: Treat this complex recovery key exactly like the master password. Store it securely, preferably printed or saved in an offline, high, security location like a dedicated hardware password manager or a safe.

Step 4: Verify the Encrypted Structure

- Unlock the vault using your password. Cryptomator mounts a virtual drive (e.g., F: or G:).

- Drop a test file (e.g.,

Budget_Q3.xlsx) into the virtual drive and lock the vault. - Using your local file explorer, navigate directly to the underlying cloud synchronized folder where the vault is stored.

- Verification: Confirm the encrypted vault structure: The root of the vault folder must contain the

masterkey.cryptomatorfile, thevault.cryptomatorfile, and a data folder namedd. - Inside the

dfolder, confirm that your original file name has been obfuscated into an unreadable string with a.c9rextension, confirming filename and content encryption.

Proof of Work Block: Cryptomator ZKE Snapshot

| Cryptographic Component | Status/Setting | Security Function |

| Encryption Algorithm | AES-256 | Data content encryption |

| Key Derivation Function (KDF) | Scrypt | Transforms user password into a strong encryption key (KEK) |

| Metadata Protection | Enabled (Filenames, folder structure obfuscated) | Prevents exposure of file context to provider |

| Key Security | KEK derived locally from user password | Ensures keys never reside in the cloud |

Step 5: Sharing Encrypted Vaults Safely

Sharing ZKE vaults requires two separate processes:

- Cloud Sharing: Share the encrypted vault directory (the folder containing the

masterkey.cryptomatoranddfolder) through the standard cloud provider sharing mechanism. - Key Exchange: Separately, you must securely share the vault master password with the authorized user. This exchange must occur over a secure, end, to, end encrypted channel (e.g., Signal or in person). Sharing only the cloud link is useless, as the recipient needs the cryptographic key, which is locally derived from the password.

Troubleshooting Common CSE/ZKE Failures

Client, side encryption introduces unique failure points related to key management and local file system integrity, which must be addressed manually.

Symptom, Fix Guide

When troubleshooting ZKE issues, focus on the integrity of the critical configuration files and the cloud sync process.

1. Cannot Open Vault (Missing Key Files)

- Error: The application fails to recognize the encrypted files and displays the message “Cryptomator could not find a vault at this path”.

- Root Cause: The critical configuration files, typically

masterkey.cryptomatororvault.cryptomator, are missing or corrupted from the root vault folder. This often happens due to cloud sync errors or accidental deletion during file cleanup. - Fix 1 (Non, Destructive): Immediately check the cloud provider’s recycle bin or file version history to restore the missing files.

- Fix 2 (Last Resort , Requires Recovery Key): If the files are permanently lost but you retained the recovery key:

- Create a temporary, empty new vault.

- Copy the functional

masterkey.cryptomatorfile from this temporary vault. - Paste and replace the missing file in the original damaged vault location.

- Select the old vault in Cryptomator, go to “Vault Options,” select “Password,” and use the recovery key (secured in Step 6.4) to reset the password and re, establish access.

2. “Unable to decrypt header of file” Error

- Error: The application logs display a specific exception:

java.io.IOException: Unable to decrypt header of file T:\vaultFormat8\d\TY\...\.c9r. The corrupted file may appear in the vault but cannot be deleted or accessed. - Root Cause: File header corruption. This occurs when the initial, crucial data block of the encrypted file is damaged, often caused by abruptly removing a USB drive or severe cloud sync interruption during a write operation. Because the header holds cryptographic initialization vectors, the file becomes cryptographically inaccessible.

- Fix (Manual Deletion):

- Unlock the vault and note the file name that is corrupted.

- Use the application’s “Reveal Encrypted File” feature to locate the specific, corrupted ciphertext file (the

.c9rpendant) in the local cloud sync folder. - Manually delete the corrupted

.c9rfile directly from the cloud folder on the operating system level, bypassing the Cryptomator virtual file system. The file can then be successfully re, copied into the vault.

Table 3: Zero, Knowledge Vault Troubleshooting: Symptom to Fix

| Symptom | Error String/Observation | Root Cause | Non, Destructive Fix |

| Cannot Open Vault | Cryptomator could not find a vault at this path. | Missing/corrupted key file (masterkey.cryptomator). |

Restore the file from backup, Recreate using the recovery key |

| File Cannot Be Deleted | Unable to decrypt header of file… | File header corruption (sync or ejective failure) | Use Reveal Encrypted File, Manually delete the corrupted .c9r pendant file |

| Large Files Corrupt | Checksum mismatch or files stop playing (e.g., > 2GB) | Cloud sync conflict or unstable volume type during transfer. | Re, copy using a reliable utility, Check/change virtual volume type (WebDAV vs. FUSE) |

| Key is Lost | Vault opens but contents are gibberish/unreadable | Loss of master password and recovery key | None. Data is permanently unrecoverable. |

Data Loss Warning: Irreversible Key Deletion

The absolute control granted by CSE and ZKE comes with a corresponding absolute liability. If a Customer Managed Key (CMK) in a Key Management Service (AWS KMS or GCP CMEK) is deleted, the data encrypted by it is immediately and permanently unrecoverable.

This principle applies equally to Zero, Knowledge systems. The key is derived locally from a password that the provider does not know. Therefore, if the master password is forgotten, and the critical recovery key is also lost, the data is technically scrambled forever. This state is not a system flaw but the fundamental, deliberate design of zero, knowledge security.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How is Zero, Knowledge different from standard End, to, End Encryption (E2EE)

Zero, Knowledge is a stricter form of E2EE. It specifically requires that the provider cannot decrypt any metadata, including file names, folder structure, or access patterns, in addition to the file contents, maximizing user privacy and minimizing information leakage.

2. Does using Client, Side Encryption (CSE) exempt my organization from HIPAA Business Associate Agreements (BAAs)

No. If a cloud service provider (CSP) creates, maintains, or transmits electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI), they are legally defined as a Business Associate, even if the data is encrypted and they lack the key. A BAA is still a necessary contractual and regulatory requirement.

3. Why should I choose SSE-KMS (CMEK) if I know the provider can still technically access the data

SSE-KMS offers superior governance required for major regulatory audits (like SOX or PCI DSS). It allows the customer to define key policies, immediately revoke key access for specific users, and leverage comprehensive audit logs that track every single request made to the key.

4. What is the practical performance cost of shifting to Zero, Knowledge Encryption

ZKE introduces CPU overhead because all data must be encrypted or decrypted locally before being written or read. This can cause perceptible latency, particularly when dealing with large files that require extensive cryptographic processing.

5. If I lose my ZKE master password, is my data really lost forever

Yes. Since the encryption key is derived directly from the master password and never stored remotely, losing both the password and the locally derived recovery key guarantees that the data is irreversibly scrambled and unrecoverable.

6. Can an external Key Manager (EKM) integrate with Zero, Knowledge systems

True ZKE systems fundamentally rely on cryptographic key derivation local to the endpoint device. This decentralized design makes integration with external, centralized Key Management Services (EKMs), which are common in SSE-KMS environments, generally unnecessary and contradictory to the zero, knowledge principle.

7. What is a “file pendant” in Zero, Knowledge storage

A file pendant is the actual encrypted representation of your original file that is stored in the cloud. Its name is a cryptographically obfuscated hash, and it uses a specific file extension (e.g., .c9r in Cryptomator) to identify it as ciphertext.

8. How can I mitigate the high request costs associated with SSE-KMS

For services like AWS S3, enabling bucket, level keys can significantly reduce costs. This configuration reduces the volume of individual requests made to KMS by using a single, unified key for many objects within a bucket, decreasing transaction fees.

9. What is the difference between a KMS key and an HSM key

A Key Management Service (KMS) is the full platform that manages the life cycle of keys (rotation, auditing, access policy). A Hardware Security Module (HSM) is the underlying physical, tamper, proof device that securely stores the most sensitive key material and executes cryptographic operations, often meeting strict standards like FIPS 140, 2 Level 3.

10. Does SSE-C protect against cloud insider threats better than SSE-KMS

SSE-C offers a higher level of technical key separation, as the provider never stores the key itself. However, SSE-KMS offers superior governance through detailed audit logs and policy enforcement (IAM), which provides stronger procedural protection against insiders by monitoring and limiting their actions. ZKE remains the only model offering technical impossibility of provider access.

Conclusion

The strategic choice in cloud encryption is defined by control. While Server, Side Encryption (SSE) models offer convenience and satisfy basic compliance mandates through procedural controls, only Client, Side Encryption (CSE), particularly the **Zero, Knowledge Encryption (ZKE)** model, provides the necessary technical defense against the cloud provider itself. By deriving and retaining keys locally, ZKE eliminates the insider threat, encrypts sensitive metadata, and guarantees maximum data sovereignty, making it the mandatory choice for highly regulated data where the core security objective is technical impossibility of provider access.