ZIP Passwords Are Not Secure: How to Use 7-Zip Correctly to Ensure AES-256 Data Protection

Immediate Answer: ZIP passwords are not secure if they rely on the default, widely supported method known as ZIPCrypto (or Zip 2.0 Legacy encryption). These formats are fundamentally flawed, relying on weak proprietary algorithms that are easily broken by off-the-shelf tools, often taking only minutes or hours. For real data protection, users must transition to a dedicated archiver like 7-Zip, select the superior .7z archive format, use AES-256 encryption, and critically, enable the “Encrypt file names” option.

The Crisis of Legacy Encryption: Why Standard ZIP Fails Instantly

Standard file archiving tools often offer an option to “password protect” a ZIP file. Unfortunately, the security offered by the default, legacy .zip format encryption is functionally nonexistent against a dedicated attacker. Relying on this format for sensitive or regulated data is a severe security risk.

The ZIPCrypto Catastrophe

The core flaw lies in the original proprietary encryption method used by the ZIP format, often referred to as Zip 2.0 or ZIPCrypto. This encryption is not merely low-security, it is vulnerable to well-known attacks, including dictionary and brute-force cracking tools readily available online.

The lack of a modern, strong Key Derivation Function (KDF) in ZIPCrypto means the process of transforming the user’s password into the cryptographic key is trivial and extremely fast. This speed allows attackers to test millions of password combinations per second, making even moderately complex passwords susceptible.

In real-world security tests conducted by cybersecurity companies, the failure rate of legacy ZIP archives is alarmingly high. Experts report an 87 percent success rate in cracking protected ZIP files within just a few hours, with the success rate rising to 97 percent within a single week. This success rate confirms that legacy ZIP encryption should never be used for protecting sensitive documentation, financial records, or client data.

Misplaced Trust and Government Warnings

A significant danger is rooted in the perception of security. When operating systems like Windows display a “password protected” prompt, users assume a basic level of defense. However, since Windows natively supports only the weak Zip 2.0 encryption, the operating system unintentionally guides the majority of users toward an insecure practice unless they install specialized, third-party software.

This widespread vulnerability has prompted warnings at the legislative level. Senator Ron Wyden addressed the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) regarding the issue, stating that many people incorrectly believe these files protect sensitive data when, in fact, they are “easily broken with off-the-shelf hacking tools”. This observation underscores that security awareness must move beyond simply requiring a password and must instead focus intensely on the underlying cryptographic method used.

Choosing the Right Tool: 7z vs. ZIP and Portability Tradeoffs

When data security is the goal, the migration from the traditional .zip format to the modern, dedicated .7z format is a mandatory upgrade. The .7z format, native to the open-source 7-Zip archiver, was specifically engineered to utilize strong, modern cryptography, making it the current standard for file encryption in this category.

The Encryption Standard: Why 7-Zip is the Necessary Upgrade

The .7z format utilizes AES-256 encryption. AES-256 is the strongest version of the Advanced Encryption Standard, adopted as a Federal Information Processing Standard, confirming its robust resistance to modern cryptanalysis. By contrast, the proprietary ZIPCrypto algorithm used by default in .zip files is not cryptographically sound.

Although some third-party archivers can apply AES encryption to a .zip file, the .7z format remains technically stronger. The .7z format was built around AES-256 from the ground up, ensuring a cleaner implementation and stronger Key Derivation Function (KDF) utilization. Attempting to retrofit the older .zip standard with AES-256 often retains complexity or reliance on weaker configuration defaults, which is why experts conclude there is “no sane reason to still use standard zip” for encrypted data.

Table 1 provides a clear technical comparison illustrating why the security choice requires switching formats.

Table 1: Encryption Security Comparison: Legacy ZIP vs. Modern 7z

| Feature | ZIPCrypto (Legacy.zip) | AES-256 (.7z) |

| Algorithm | Weak (Proprietary ZIPCrypto) | Strong (AES-256) |

| Key Derivation (KDF) | Simple Hash (Trivial) | Iterated SHA-256/PBKDF2 (Brute-Force Resistance) |

| Cracking Resistance | Extremely Low (Hours/Days) | High (Scales with password strength) |

| Metadata Protection | File Names Exposed by Default | Optional (Must check “Encrypt file names”) |

| Native Windows Support | High (Built-in) | Low (Requires 7-Zip/Compatible Tool) |

The Portability vs. Security Conundrum

The decision to use modern encryption involves accepting a minor tradeoff in portability. The only benefit of legacy ZIPCrypto is that Windows can extract the files natively. Once AES encryption is applied, whether in a .zip or .7z container, Windows loses its native ability to extract the archive, meaning the recipient will need third-party software regardless.

If the recipient must install a tool anyway to handle the strong encryption, it is illogical to use the older .zip format. The slight friction caused by requiring the recipient to install 7-Zip (or Ez7Z for macOS/Linux users) is a mandatory security gate that ensures reliable encryption.

Prerequisites and Safety Check

Before proceeding with encryption, it is essential to prepare the environment to ensure both speed and safety.

Required Software

The tutorial assumes the user has downloaded the latest, stable version of 7-Zip for PC. Using the official source is crucial, as downloading compromised software poses a severe malware risk.

System Capability

Most modern CPUs include hardware acceleration for AES known as AES-NI (Advanced Encryption Standard New Instructions). This dedicated instruction set dramatically accelerates cryptographic operations, ensuring that implementing strong encryption does not become a productivity bottleneck.

Mandatory Safety

Data integrity must be prioritized. While 7-Zip is highly reliable, any operation involving file writes carries a small risk of corruption due to power failure or disk error. Users should always back up the original files before creating the encrypted archive.

Tutorial: 7-Zip Done Right (The Secure.7z Archive)

Creating a secure archive requires specific configuration steps within 7-Zip that differ from the default settings. Missing even one crucial checkbox can compromise the integrity and privacy of the encrypted data.

The Critical “Gotcha”: Encrypting File Names

The single most common mistake made by professionals using file archivers is failing to check the “Encrypt file names” box. If this step is omitted, an attacker gains immediate access to the names, sizes, and internal structure of every file within the archive without needing the password. This metadata leakage reveals exactly what sensitive documents are contained within, severely aiding targeted brute-force attempts and social engineering attacks.

Step-by-Step Overview for Creating a Secure.7z File

This overview utilizes the strongest combination of format, algorithm, and configuration settings available in 7-Zip.

- Step 1: Get the Tools and Select Your Data

- Launch the 7-Zip File Manager and navigate to the directory containing the file or files that require encryption . Select the target data.

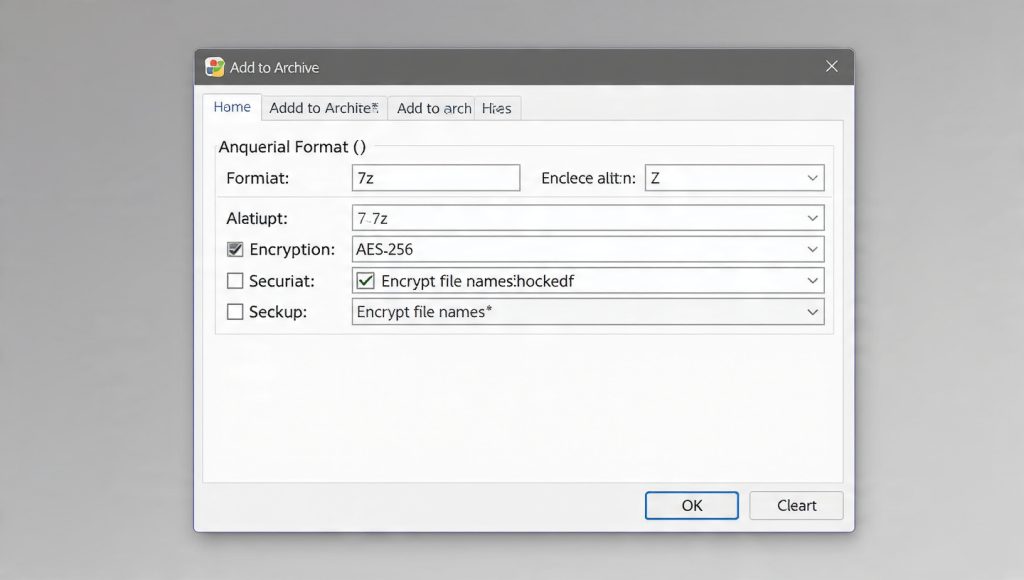

- Right-click the selected file(s) or folder, hover over 7-Zip, and click Add to Archive… This action opens the configuration dialog box.

- Step 2: Define Archive Format and Encryption Strength

- In the resulting “Add to Archive” dialog box, set the Archive format: dropdown menu to 7z. This choice dictates the use of the modern architecture and the superior Key Derivation Function.

- Under the Encryption section, ensure the Encryption method: is set to AES-256.

- Step 3: Define a High-Entropy Password

- The strength of AES-256 encryption is ultimately capped by the strength of the user-defined password.

- Enter and re-enter a strong, unique password in the designated fields .

- The password should be a unique passphrase of at least 15 characters. Following organizational guidelines, such as those recommended by institutions like LSE, requires the password to be 8 or more characters long, containing at least one capital letter, one lowercase letter, and one numeral. Although 7-Zip’s KDF provides defense, a weak password will still be rapidly cracked.

- Step 4: Enable Header Encryption (The Mandatory Security Layer)

- This is the security step most often overlooked, compromising metadata privacy.

- Crucially, check the box labeled Encrypt file names . This action encrypts the central directory, ensuring that no file information is exposed until the correct password is provided.

- Finally, click OK to generate the secure .7z archive. By default, the output file will be placed in the same directory as the original data.

- Step 5: Verify the Archive Security

- Security verification is mandatory to confirm that the header encryption worked as intended.

- Attempt to open the newly created .7z file using the 7-Zip application. If the archive was created securely, 7-Zip must immediately prompt for the password before displaying any file names or folder structures . If a list of files is visible before the password prompt appears, the header encryption failed, and the data must be re-archived immediately.

The Deep Dive: How 7z Protects Your Data (KDF Analysis)

The fundamental difference between legacy ZIP and modern 7z encryption lies not just in the algorithm (AES-256 is mathematically sound and fast) but in the pre-processing step that protects the user-defined password from automated cracking: the Key Derivation Function (KDF).

Key Derivation Functions: Slowing Down the Attacker

The purpose of a KDF is to take a human-readable password, which is prone to being guessed, and transform it into the actual, highly randomized 256-bit cryptographic key needed for AES. This transformation process must be intentionally slow and iterative to defeat specialized hardware and software designed for fast, automated brute-force attacks.

7-Zip employs a derivation function based on the SHA-256 hash algorithm. The developers understood that AES-256, while strong, requires the password transformation process itself to be computationally expensive to maximize resistance to exhaustive search attempts.

Iteration Counts and Brute-Force Resistance

Early technical reviews of 7-Zip noted variations in its custom KDF implementation and questioned its iteration counts, with some analyses citing low figures such as 1,000 passes for older PBKDF2/SHA1 implementations. This historical confusion often leads to skepticism regarding 7-Zip’s actual security.

However, modern analysis of cracking tools confirms the current implementation provides substantial computational defense. Security researchers who reverse-engineer these processes confirm that current 7-Zip archives use a high number of iterations, citing figures around 130,000 SHA-256 transformations per password guess. This overhead is sufficient to render brute-force attacks against strong passwords impractical.

While standards like OWASP recommend iteration counts in the hundreds of thousands (e.g., 600,000 for PBKDF2-HMAC-SHA256), 7-Zip’s current implementation ensures that the time taken for each password guess is artificially lengthened significantly compared to legacy ZIP, which offers virtually no KDF overhead. This transformation turns a potential three-hour cracking job into a task requiring decades of dedicated computing power, provided the user selects a strong password.

Header Encryption Explained: Hiding the Blueprint

The critical step of checking “Encrypt file names” is equivalent to encrypting the archive’s central directory structure, the header. This structure includes the file list, file sizes, compression algorithms used, and timestamps.

If the header remains unencrypted, an attacker benefits from three major advantages, even if they cannot decrypt the file contents:

- Context and Motivation: The attacker instantly knows the specific contents (e.g., “Q1-Financial-Report.xlsx,” “CEO-Email-Archive.pst”). This metadata is often enough to confirm the data is worth the effort to crack, or to fuel targeted social engineering attempts.

- Targeted Cracking: Knowing the names and the size of the files helps tailor dictionary attacks based on known naming conventions (e.g., trying passwords that include the year or project names).

- Authentication Bypass: Visible file names confirm that the archive is a legitimate, viable target, reducing the chance that the attacker wastes time testing corrupt files.

Privacy requires concealing both the content and the context of the data.

Proof of Work and Performance Benchmarks

A common barrier to adopting high security is the perception that strong encryption will significantly slow down workflow. Modern hardware and optimized algorithms dismantle this concern.

Encryption Speed Analysis

The speed of the encryption process is often confused with the speed of the compression process. The use of hardware instructions, such as Intel’s AES-NI, allows modern CPUs to perform AES-256 operations at incredibly high speeds.

An analysis of modern CPU performance shows that AES encryption operates at roughly $1.3$ cycles per byte. For a typical $2.2$ GHz processor, encrypting a $1$ GB file takes approximately $0.63$ seconds. The encryption step is so fast that it is essentially instantaneous to the user.

The Compression Bottleneck

The actual bottleneck in creating a large .7z file is the compression algorithm, typically LZMA or LZMA2, which is designed to reduce file size but requires significant processing time. LZMA compression speeds generally operate in the low single-digit MB/s range (around $2–8$ MB/s on a $4$ GHz CPU).

For example, compressing a large $11$ GB file (like a virtual machine image) on a powerful system can take about $60$ seconds using the “Fastest” compression mode. This proves that enabling the maximum security level (AES-256) imposes a negligible time cost compared to the mandatory compression overhead. Security does not need to compromise productivity on modern devices.

Table 2: AES-256 Encryption Performance Benchmarks (Modern CPU with AES-NI)

| Task | Hardware/Reference | Approximate Speed |

| AES-256 Encryption Throughput | Modern CPU (2.2 GHz) w/ AES-NI | $\sim 1.3$ cycles/byte |

| Estimated 1 GB Encryption Time | 2.2 GHz CPU w/ AES-NI | $\sim 0.63$ seconds |

| 7-Zip LZMA Compression Speed | 4 GHz CPU (2 threads) | $\sim 2–8$ MB/s |

| 11 GB VM Compression (.7z Fastest) | RAMDISK Benchmark | $\sim 60$ seconds (Compression time) |

Settings Snapshot: The Secure Configuration

For guaranteed security and compliance, the final archive configuration must adhere to these exact settings:

- Archive Format: 7z

- Encryption Method: AES-256

- Check Box Status: Encrypt file names (Checked ON)

- Compression Method: LZMA2 (Default/Recommended)

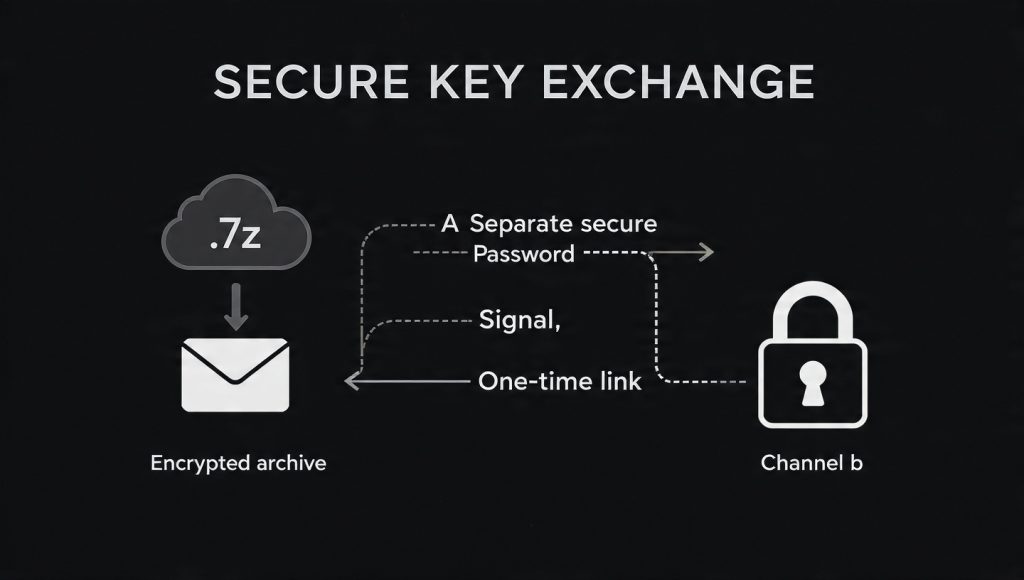

Secure Key Exchange: Sharing the Archive Safely

A perfectly encrypted archive is immediately compromised if the password, or key, is transmitted using an insecure method. The weakest link in data security is often the human decision regarding password distribution.

The Key Distribution Challenge

Sending the archive via email and then placing the password in the body of the same email completely defeats the encryption purpose. If the communication channel (the email server or the transit route) is compromised, the attacker gains both the encrypted data and the key required to decrypt it instantly.

The principle of key distribution requires using an authenticated, secure channel separate from the channel used to send the archive itself.

Recommended Key Exchange Methods

- End-to-End Encrypted Messengers: The most secure method involves using applications designed specifically for secure, authenticated communication. Tools like Signal, which rely on strong protocols such as X3DH (Extended Diffie-Hellman) or PQXDH, establish a shared secret key between parties, providing forward secrecy and cryptographic deniability. The password should be sent via this E2E encrypted platform only after the archive has been delivered via email or cloud storage.

- One-Time Secret Services: For external clients or recipients who may not be integrated into a shared secure messaging platform, ephemeral link services provide a usable security bridge. Services like OneTimeSecret allow the user to generate a secure link to the password that is accessible only once by the recipient before the secret is permanently destroyed. This introduces a time-limited security window that significantly limits interception risk.

- Voice or Physical Exchange: For the highest level of assurance, the password should be exchanged verbally or written down physically. This ensures the decryption key never touches an insecure digital network, bypassing the vulnerabilities inherent in email or standard messaging protocols.

Troubleshooting and Recovery

Even with optimal encryption, issues during transfer, disk storage, or extraction can lead to frustrating and critical errors. When an archive fails to extract, the problem is often rooted in data integrity issues rather than cryptographic failure.

Troubleshooting Procedure: Non-Destructive First

Before attempting complex recovery methods, follow these non-destructive steps:

- Restart and Reboot: A simple restart of the 7-Zip application or a reboot of the computer often resolves temporary resource conflicts or file locks that prevent access or extraction.

- Update Software: Ensure both the sender and the receiver are using the absolute latest stable version of 7-Zip. Older versions may not correctly support current compression methods (LZMA2) or security standards.

- Scan for Malware: Viruses or other malicious software can corrupt archive data by tampering with disk sectors or file headers. Running a comprehensive malware scan (e.g., Windows Defender Quick scan) is a mandatory diagnostic step.

- Re-Download: If the archive was downloaded from the internet, network interruptions often cause partial file corruption. Re-downloading the file from the source, if reliable, is the easiest fix for transfer errors.

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: 7-Zip Encryption Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom/Error Message | Root Cause | Immediate Fix/Action |

| CRC Failed in 7Zip | Cyclic Redundancy Check failure, indicating data corruption (bad disk sectors, transfer error), or virus infection. | Run a hard drive diagnostic (chkdsk), update 7-Zip, or utilize an alternative compression tool to attempt extraction. |

| Data Error | Incorrect password, corrupted file header, or damaged data blocks during write/transfer. | Re-enter password carefully, reboot the PC, or attempt to re-download the archive from a reliable source. |

| Unsupported Method | The archive was created using a non-standard feature (e.g., an experimental SFX file) or a very new algorithm not recognized by the recipient’s 7-Zip version. | Ensure the recipient has the latest stable 7-Zip. If using SFX, specialized command-line tools might be needed to repair the executable header. |

| Header is Damaged | Metadata corruption. If file names were not encrypted, the damage might be easier to address. | Use professional file recovery software. In extreme, last-resort cases, manual attempts to replace the corrupted binary header bytes may be possible, but this is highly technical. |

Last-Resort Options (With Data Loss Warnings)

If the data corruption is extensive and non-destructive repairs fail, the following methods are highly technical and carry an inherent risk of data loss:

- Partial Extraction: Specialized recovery tools may attempt to bypass the corrupt sections of the archive and extract only the viable, uncorrupted data blocks. This usually results in a set of usable files, but others may be missing or internally damaged.

- Replacing Corrupted Sections: If an exact, known-good copy of the archive or the original files exists, experts can sometimes create a new, similar archive and replace the corrupted segments of the bad file with the corresponding good segments. This procedure requires advanced knowledge of the .7z file structure.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why does Windows not natively support AES-256 encryption in ZIP files?

Windows prioritizes compatibility and only supports the weakest form of ZIP encryption (Zip 2.0 Legacy/ZIPCrypto) natively. It does not support AES-256 for ZIP because that protocol requires dedicated external software, defeating the initial goal of native extraction.

Q: If I use 7-Zip and the .7z format, do my recipients need 7-Zip too?

Yes. Since the .7z format and AES-256 are proprietary extensions, the recipient must install 7-Zip or a compatible alternative (like Ez7Z on Mac/Linux) to decrypt and access the files. Standard operating systems cannot read this format.

Q: Is it true that 7-Zip’s encryption can be brute-forced faster than other tools?

This is misinformation based on older reports. While early versions had non-standard KDFs, the current 7-Zip implementation uses high-iteration SHA-256 key derivation (around 130,000 passes), making automated brute-force cracking impractical for any moderately strong password.

Q: What is the biggest security mistake people make when encrypting files?

Failing to enable header encryption (checking “Encrypt file names“). This negligence exposes the file list, file sizes, and metadata to anyone who holds the archive, severely compromising privacy and helping attackers tailor their efforts.

Q: Does AES-256 encryption significantly slow down file creation?

No. Due to hardware acceleration (AES-NI), the encryption process itself is extremely fast, performing at speeds over a gigabyte per second. The time taken to create the archive is dominated by the compression algorithm (LZMA2), not the security protocol.

Q: Can I use 7-Zip to encrypt a standard .zip file with AES-256?

7-Zip can do this, but the .7z format remains the superior and recommended choice. The .7z format offers inherently better structure and a more robust Key Derivation Function implementation.

Q: How long should my password be for a 7z archive?

A strong password should be at least 15 characters long, using a complex mix of capital letters, lowercase letters, and numerals. This length is critical because it exponentially increases the time required for KDF-protected brute-force attempts.

Q: What is the risk of using 128-bit AES encryption instead of 256-bit?

While 128-bit AES is still considered strong today, 256-bit offers a higher security margin. Since AES-256 is nearly as fast as AES-128 on modern hardware, there is no technical justification to use the lower standard for sensitive data.

Q: What is the minimum recommended salt length for encryption?

The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) recommends a salt length of at least $128$ bits ($16$ bytes) to effectively prevent pre-computed dictionary attacks and rainbow tables.

Q: Why are 7-Zip archives often more difficult for password crackers to target?

The general ecosystem of password cracking tools is heavily skewed toward legacy ZIP due to its historical prevalence. Finding efficient, specialized software to target 7z-AES archives is typically more challenging than finding standard ZIP cracking tools.

Q: Can I recover an encrypted 7z file if I forget the password?

No. Strong AES-256 encryption, when implemented correctly, is designed to have no master keys or backdoors. If the password is forgotten or lost, the data is rendered permanently inaccessible.

Q: I received an error saying ‘7z cannot find the path.’ What do I do?

This usually occurs when the archive contains internal files with extremely long names, which exceeds the path length limits of the Windows operating system. Extracting the archive contents directly to a root directory, such as C:\Temp, typically resolves this issue.

Q: Why is metadata leakage (unencrypted headers) dangerous if the content is encrypted?

Metadata leakage compromises the privacy of the operation by providing context. Knowing that an archive contains specific, sensitive materials increases the attacker’s motivation and allows them to target their cracking resources more efficiently.

Q: How does 7-Zip handle file names that use Unicode characters?

The .7z format was designed with modern requirements in mind, explicitly supporting Unicode file names. This ensures cross-platform and international compatibility, which older archive formats often struggle with.

Q: What alternative tools exist for Mac or Linux users to decrypt .7z files?

macOS users can install and utilize Ez7Z, which is compatible with 7-Zip encrypted files. Linux systems typically rely on command-line utilities like p7zip or similar archiving tools that support the .7z format.

Conclusion and Actionable Next Steps

The evidence confirms that the security of archived data is defined not by the presence of a password, but by the cryptographic implementation used to protect it. Legacy ZIPCrypto is a defunct security measure that should be retired immediately for any sensitive data transmission or storage.

To ensure verifiable data protection, professionals must stop using the standard ZIP functionality for encryption. The mandatory protocol for securing data requires the use of a tool designed for modern security.

Action: If sensitive files are currently relying on standard password-protected .zip files, those files must be re-archived immediately using the robust 7-Zip / .7z / AES-256 protocol. Crucially, verify that the “Encrypt file names” option is checked during creation. This transition is simple to execute, yet it delivers a foundational level of security that legacy formats cannot provide.