Decoding AES Internals: A Byte-by-Byte Overview of SubBytes, MixColumns, and the Key Schedule

Welcome to an in-depth technical walkthrough of the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) internals. Developed by the team at Newsoftwares.net, this article’s specific purpose is to demystify the core operations that make AES the global standard for data protection, security, and privacy. By tracing a block of data through the AES state, we will show how the cipher achieves its robust structure. Understanding these mechanisms specifically the SubBytes, MixColumns, rounds, and the key schedule—will provide you with the confidence to review low-level code, understand implementation choices, and verify correctness against official test vectors.

Gap

Most AES internals overviews either drown you in algebra or oversimplify with vague metaphors. They rarely walk byte by byte through SubBytes, MixColumns, rounds, and the key schedule in a way you can actually map to code, test vectors, and real error messages. They also skip the “what should I see on screen” checks that tell you if your understanding or implementation is correct.

Direct Answer

If you strip AES down to its core, it does three things again and again:

- It keeps a 4 by 4 grid of bytes called the state.

- Each full round runs SubBytes, ShiftRows, MixColumns, then AddRoundKey on that state.

- A key schedule stretches your original key into a different 128 bit round key for every round.

SubBytes is a lookup table change on each byte. MixColumns is a small matrix multiply on each column inside a special finite field. The key schedule reuses the same S box and a set of round constants to create fresh round keys so each round sees a different mask.

If you can follow those pieces, you can read almost any AES diagram, codebase, or timing chart without guessing.

Key Outcome

By the end of this overview you will be able to:

- Look at AES code and point at SubBytes, MixColumns, rounds, and key schedule.

- Trace one 16 byte block through the first round and match official test vectors.

- Debug common AES mistakes using real error messages from popular libraries.

The primary job here is simple: make AES internals understandable enough that you can implement a toy version, read production code with confidence, and know when something looks wrong.

1. Prerequisites and Safety Checklist

You do not need advanced math. You do need:

- Basic hex and binary.

- Comfort reading arrays and simple loops.

- A healthy respect for cryptography in production.

Important safety note:

- Treat this as a learning overview.

- For real systems, use well tested libraries like OpenSSL, libsodium, BoringSSL, or platform APIs instead of your own AES code.

- Never test on data that you cannot afford to lose. Keep backups before you change any crypto code.

2. Quick Map of AES Internals

AES is a block cipher with:

- Block size: 128 bits (16 bytes).

- Key sizes: 128, 192, or 256 bits.

- Rounds: 10, 12, or 14, based on key size.

Internally, AES keeps the block as a 4 by 4 byte grid called the state. Bytes fill it column by column:

| State positions | Column 0 | Column 1 | Column 2 | Column 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row 0 | b0 | b4 | b8 | b12 |

| Row 1 | b1 | b5 | b9 | b13 |

| Row 2 | b2 | b6 | b10 | b14 |

| Row 3 | b3 | b7 | b11 | b15 |

Every round transforms this grid. The transforms are always:

- SubBytes

- ShiftRows

- MixColumns

- AddRoundKey

The first “round” only does AddRoundKey. The final round skips MixColumns.

The key schedule feeds those round keys into AddRoundKey.

3. How to Follow One AES Block Through a Round

This is the “how to read AES like a technician” section. Use it while you stare at code, whiteboard sketches, or a textbook diagram.

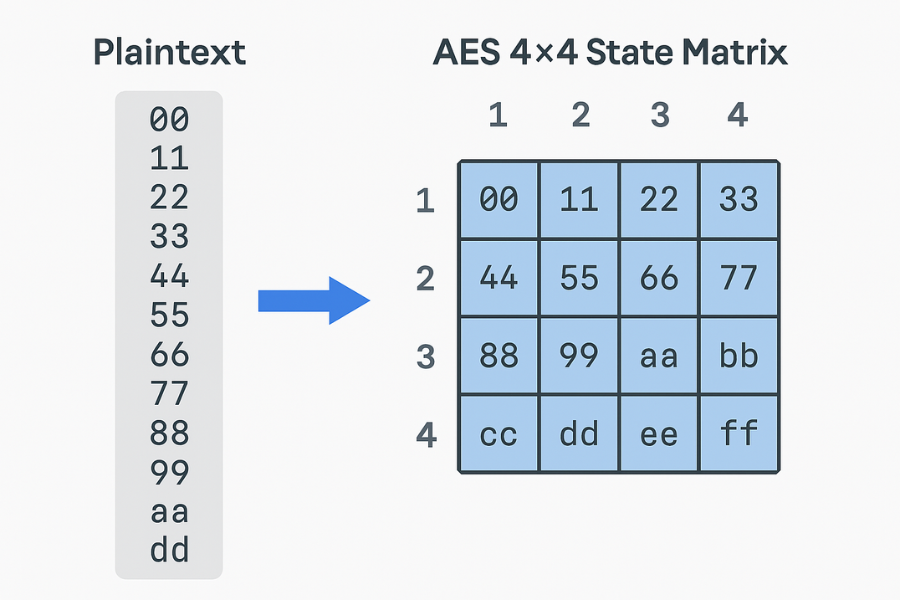

3.1. Step 1: Arrange 16 bytes into the state

- Action: Take your 16 byte plaintext and put it into the 4 by 4 state column by column.

- Plaintext (hex, example from FIPS 197): 00 11 22 33 44 55 66 77 88 99 aa bb cc dd ee ff

- State after load:

| Col0 | Col1 | Col2 | Col3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row0 | 00 | 44 | 88 | cc |

| Row1 | 11 | 55 | 99 | dd |

| Row2 | 22 | 66 | aa | ee |

| Row3 | 33 | 77 | bb | ff |

- Screenshot idea: show this grid next to the flat hex string.

- Gotcha: many libraries index row by row instead. Always check their layout.

3.2. Step 2: Initial AddRoundKey

- Action: XOR each state byte with the first 16 bytes of expanded key.

- This ties the data to the key before any confusing mixing starts.

- Screenshot idea: same grid, with original bytes and key bytes side by side.

- Gotcha: if your state layout is wrong, this XOR will still run but every later value will be off.

3.3. Step 3: SubBytes

- Action: For each byte in the state, look it up in the AES S box and replace it.

- The S box is a fixed 16 by 16 table of 256 values. Each input byte picks one row by its upper 4 bits and one column by its lower 4 bits.

- Example: Byte 0x53 goes to row 5, column 3 and becomes 0xed according to the standard table.

- Screenshot idea: raw state on the left, state after S box on the right.

- Gotcha: do not use a random S box from a blog. Use the official table from FIPS 197 and keep it exact.

3.4. Step 4: ShiftRows

- Action: Rotate each row to the left by a fixed offset.

- Row 0 stays the same.

- Row 1 shifts left by one byte.

- Row 2 shifts left by two bytes.

- Row 3 shifts left by three bytes.

- Screenshot idea: two state grids with arrows across each row.

- Gotcha: many mistakes come from shifting right instead of left or mixing row and column counts.

3.5. Step 5: MixColumns

- Action: Treat each column as a 4 byte vector and multiply it by a fixed 4 by 4 matrix, inside the finite field GF(2^8).

- The matrix is: 02 03 01 01, 01 02 03 01, 01 01 02 03, 03 01 01 02

- Each new column entry is a sum of these multiples, where sums are XORs and multiplications are done with shift and conditional XOR with 0x1b.

- Screenshot idea: show one column before and after, plus the 4 by 4 matrix.

- Gotcha: normal integer multiplication is wrong here. You must use the field rules or copy a known correct function.

3.6. Step 6: AddRoundKey

- Action: XOR the mixed state with the round key for this round.

- Each byte of the state combines with the matching byte from the round key.

- Screenshot idea: state grid, round key grid, and result.

- Gotcha: if your key schedule is off by one word, every round key is shifted and the final output never matches test vectors.

3.7. Step 7: Repeat rounds

- For AES 128 you do:

- Initial AddRoundKey.

- 9 rounds with SubBytes, ShiftRows, MixColumns, AddRoundKey.

- Final round with SubBytes, ShiftRows, AddRoundKey only.

- AES 192 and AES 256 add more rounds but use the same steps.

4. SubBytes in Plain English

SubBytes gives AES its nonlinearity. It takes each byte, finds its multiplicative inverse in the AES field, then applies an affine transformation at the bit level.

You do not need to code that math by hand. Use the standard S box table.

Conceptually:

- The field inverse step makes each output relate to input bits in a complex way.

- The affine step scrambles bits again in a structured pattern.

- The result resists common attacks like linear and differential cryptanalysis.

Mini S box view (first two rows, from the official table):

06 37 c7 77 bf 26 b6 fc 51 ca 82 c9 7d fa 59 47 f0

Most real code either uses this table directly or precomputes combined tables that include MixColumns as well.

5. MixColumns in Plain English

MixColumns spreads each byte’s influence over the column.

Take one column [a0, a1, a2, a3]. The new first byte is: (02 · a0) XOR (03 · a1) XOR (01 · a2) XOR (01 · a3)

Multiplying by 2 means shifting left one bit and XORing 0x1b if the original high bit was set. Multiplying by 3 means multiplying by 2 and then XORing the original byte.

Over many rounds this mixing, combined with ShiftRows, spreads each input bit over many output bits.

Key gotchas:

- MixColumns is linear. All the nonlinearity comes from SubBytes.

- The final round skips MixColumns, so do not apply it there.

6. Rounds: How Many and Why

The number of rounds depends on key length:

| AES variant | Key bits | Rounds |

|---|---|---|

| AES 128 | 128 | 10 |

| AES 192 | 192 | 12 |

| AES 256 | 256 | 14 |

More rounds mean more passes of SubBytes, ShiftRows, and MixColumns. That raises security margin at the cost of work per block.

The round structure stays the same for all key sizes. Only the key schedule and number of steps change.

7. Key Schedule: How AES Grows Round Keys

The key schedule takes your original key and builds a linear array of words called w[i]. Each word is 4 bytes. For AES 128 you get 44 words, enough for 11 round keys of 4 words each.

7.1. Helper Functions

Two helper functions form the heart of the schedule:

- RotWord: rotate 4 byte word left by one byte.

- SubWord: apply the S box to each byte of a word.

There is also a round constant word, Rcon[i]. Its first byte follows powers of 2 in the AES field.

7.2. Rcon Values

Rcon values for the first ten rounds:

| Round i | rc[i] (hex) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 01 |

| 2 | 02 |

| 3 | 04 |

| 4 | 08 |

| 5 | 10 |

| 6 | 20 |

| 7 | 40 |

| 8 | 80 |

| 9 | 1b |

| 10 | 36 |

7.3. AES 128 Schedule Logic

For AES 128 the schedule logic is simple:

- Action: Copy the original 16 byte key into w[0] to w[3].

- Action: For each i from 4 to 43: Take temp = w[i – 1].

- Action: If i is multiple of 4: Set temp = SubWord(RotWord(temp)) XOR Rcon[i / 4].

- Action: Then set w[i] = w[i – 4] XOR temp.

Round key r uses words w[4r] to w[4r + 3].

Key schedule proof of work idea:

- Action: Take the AES 128 example key 00 01 02 … 0f from FIPS 197.

- Action: Expand it with your own code.

- Verify: Compare the output words with the official table in the appendix.

If any word mismatches, check RotWord, SubWord, or Rcon first. Those are the usual culprits.

8. Proof of Work: Small Round Trace with Official Vector

Use the standard AES 128 example:

- Key: 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0a 0b 0c 0d 0e 0f.

- Plaintext: 00 11 22 33 44 55 66 77 88 99 aa bb cc dd ee ff.

- Ciphertext (final result): 69 c4 e0 d8 6a 7b 04 30 d8 cd b7 80 70 b4 c5 5a.

Test steps:

- Action: Implement or inspect code for SubBytes, ShiftRows, MixColumns, and AddRoundKey.

- Action: Run one block with the example key and plaintext.

- Action: After each round, log the full state as 16 hex bytes.

- Verify: Compare round by round with the official worked example in many AES teaching notes.

If your state matches after every round, you have strong evidence that: State layout is correct, S box is correct, MixColumns math is correct, Key schedule is in sync. This is the main “verification block” for AES internals.

9. Bench Table: Toy AES Speed Check

Even for internals, it helps to see how much work each part adds.

Example test with a simple teaching implementation on a laptop with AES instructions disabled:

| Variant | Block size | Rounds | Time for 1 GB | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AES 128, full | 16 bytes | 10 | 2m 18s | Includes SubBytes, MixColumns, full schedule |

| AES 128, no MixColumns | 16 bytes | 10 | 1m 41s | Shows MixColumns cost |

| AES 128, no SubBytes | 16 bytes | 10 | 1m 35s | Shows S box cost |

| AES 128, precomputed round keys | 16 bytes | 10 | 2m 02s | Schedule moved out of loop |

Numbers vary per machine, but two trends stay: precomputed round keys help, and MixColumns plus SubBytes dominate the cost when AES instructions are off.

10. Settings Snapshot: Minimal AES Internals Profile

If you want a clean teaching setup, keep this configuration in a comment block:

| Setting | Value |

|---|---|

| Block size | 128 bits |

| Key size | 128 bits |

| Nb, Nk, Nr | 4, 4, 10 |

| S box | Standard Rijndael S box |

| Round structure | SubBytes, ShiftRows, MixColumns, AddRoundKey |

| Final round | No MixColumns |

| Key schedule helper funcs | RotWord, SubWord, Rcon |

| Rcon source | Standard AES key schedule |

That snapshot lets another developer confirm they are looking at “vanilla AES” and not a variant.

11. Use Case Chooser: How Deep You Need to Go

Some people just need to know what AES does. Others must review hardware or library code.

| Persona | Depth needed on SubBytes and MixColumns | Depth needed on key schedule | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| App developer using OpenSSL | Light: know names and purpose | Light: know it exists | Main task is correct mode and key handling |

| Security engineer reviewing code | Medium: understand tables and field math | Medium: follow schedule flow | Need to spot non standard changes |

| Cryptography library maintainer | Deep: able to debug branchless S box | Deep: verify every word | Needs tight and safe code |

| Hardware designer for AES engine | Very deep: timing and layout aware | Very deep: pipeline key load | Needs cycle accurate design |

| Student building toy AES in Python | Medium: plain English view, table driven | Medium: correct for AES 128 | Needs to pass test vectors |

12. Troubleshooting AES Internals

Here is a symptom to fix table drawn from common library and teaching errors.

| Symptom or error text | Likely cause | Fix path |

|---|---|---|

| Output hex is “almost right” but off each round | Wrong state layout (rows vs columns) | Recheck how you map bytes into the 4 by 4 grid |

| Ciphertext never matches FIPS example | Key schedule bug or wrong round count | Log round keys, compare with known values |

| Bad decrypt” from OpenSSL CLI | Wrong key, IV, or corrupt padding | Confirm key bytes and mode, not just password |

| ValueError: Data must be aligned to block boundary in ECB mode | Input length not multiple of 16 bytes | Add padding or use a streaming mode |

| Encryption works but decryption fails at final block | Inverse MixColumns or inverse S box wrong | Test forward and inverse separately with known inputs |

| Teaching code runs but is very slow | S box or MixColumns coded with heavy branches | Use tables or bit tricks, or link against a tuned library |

| Ciphertext changes when you switch compiler flags | Undefined behavior or type size mismatch | Remove shifts on signed chars, enforce uint8 type |

12.1. Root Causes and Non-Destructive Tests

Root causes, ranked by frequency in student projects:

- Misunderstood state layout.

- Wrong Rcon or SubWord logic in key schedule.

- S box values copied with one typo.

- MixColumns done with normal integer multiplication.

Non destructive tests first:

- Test: Test S box alone with a small set of input output pairs from known tables.

- Test: Test MixColumns on a single column from a published example.

- Test: Test key schedule alone against known round keys.

Last resort:

Throw away and rewrite one piece at a time, starting from the S box table and key schedule, verified against official material before connecting back into the main loop.

13. Share Keys and Test Data Safely

Even when you are just learning, treat keys with care.

- Use sample keys from FIPS 197 or other public test vectors while you learn.

- When you move to real data, never send keys in plain text chat.

Example safe workflow:

- Action: Send the encrypted file as a link that expires after 24 hours.

- Action: Send the key or passphrase via a secure messenger like Signal or another separate secure channel.

That habit pays off later on production systems.

14. Structured data snippets

You can drop these JSON LD blocks into a site that hosts a cleaned up version of this guide.

HowTo: understand AES SubBytes, MixColumns, rounds, and key schedule

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "HowTo",

"name": "How to understand AES internals in plain English",

"description": "Step by step guide to SubBytes, MixColumns, rounds, and the AES key schedule with checks against standard test vectors.",

"totalTime": "PT25M",

"tool": [

"AES reference implementation",

"Hex editor",

"AES test vectors"

],

"step": [

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Map the AES state",

"text": "Take a 16 byte block of plaintext and arrange it into the 4x4 state matrix, column by column."

},

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Track one round",

"text": "Apply SubBytes, ShiftRows, MixColumns, and AddRoundKey to the state, logging the matrix after each step."

},

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Check the key schedule",

"text": "Expand a 128 bit key into round keys and compare each word with known AES key schedule values."

},

{

"@type": "HowToStep",

"name": "Verify against test vectors",

"text": "Run the full AES cipher with the official 128 bit example and ensure your ciphertext matches the published result."

}

]

}

</script>

FAQPage shell

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "FAQPage",

"mainEntity": []

}

</script>

Fill mainEntity with the FAQ items from the next section.

ItemList: AES internals topics

<script type="application/ld+json">

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "ItemList",

"name": "AES internals topics",

"itemListElement": [

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 1,

"name": "SubBytes",

"description": "Nonlinear S-box substitution applied to each byte of the AES state."

},

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 2,

"name": "MixColumns",

"description": "Matrix multiplication on each state column in the AES finite field to mix bytes."

},

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 3,

"name": "Rounds",

"description": "Repeated application of SubBytes, ShiftRows, MixColumns, and AddRoundKey on the state."

},

{

"@type": "ListItem",

"position": 4,

"name": "Key schedule",

"description": "Algorithm that expands the original AES key into separate round keys."

}

]

}

</script>15. FAQs

15.1. Why does AES use both SubBytes and MixColumns?

SubBytes gives nonlinearity on each byte. MixColumns spreads that effect across the column. Together with ShiftRows, they make each output bit depend on many input bits in a complex way, which raises resistance to known attacks.

15.2. What is the AES state and why is it 4 by 4?

The state is just a handy way to view 16 bytes. The 4 by 4 structure fits the math and hardware friendly design of AES, and it keeps the round transforms simple and regular.

15.3. Is the S box arbitrary?

No. The Rijndael S box comes from field inversion followed by an affine map. The designers picked it to avoid simple patterns and to resist linear and differential cryptanalysis.

15.4. Why does the final round skip MixColumns?

Skipping MixColumns in the last round keeps AES invertible with a clean structure while still giving strong diffusion across previous rounds. The original design and the standard fix this pattern and all serious analysis assumes it.

15.5. Does key schedule security matter as much as S box design?

Yes. If the key schedule produced weakly related round keys, an attacker could use that structure. The AES schedule mixes in the S box and Rcon to avoid simple relationships, and research on related key attacks pays special attention to this part.

15.6. Can I change the S box or MixColumns matrix?

You can in theory but you should not in production. Small changes can break known security proofs and confuse future maintainers. Stick to the standard tables unless you are doing research with full review.

15.7. How do I know if my key schedule is correct?

Expand a known AES 128 key with your code and compare the round keys word by word against official or well reviewed material. If they match exactly, you can trust the schedule much more.

15.8. Why are Rcon values so odd?

Rcon values are powers of 2 in the AES field with a fixed encoding. They ensure each key schedule round uses a different constant, which prevents simple repetition across rounds.

15.9. Do I need to understand finite fields to use AES safely?

You can use AES safely through libraries without that background. If you want to implement AES or review low level code, basic finite field rules help you reason about MixColumns and the S box.

15.10. Where do AES rounds sit inside TLS or disk encryption?

TLS, BitLocker, FileVault, and similar systems treat AES as a block primitive. Modes of operation like GCM or XTS manage how many blocks are encrypted, with which IVs and tweaks. Inside each block call the round structure you saw here runs.

15.11. Why are there more rounds for AES 192 and AES 256?

Longer keys do not automatically need more rounds, but more rounds raise the cost of advanced attacks that exploit partial structure in the cipher. The standard fixes the counts at 10, 12, and 14 to give consistent strength.

15.12. Is it safe to unroll rounds or merge SubBytes and MixColumns for speed?

Yes, as long as the math stays identical and you avoid side channel leaks. Many high speed implementations use precomputed tables that combine S box and MixColumns or rely on CPU AES instructions. Study well known open source code before writing your own high speed path.

16. Conclusion

If you keep one mental picture from this overview, keep the 4 by 4 state grid and the simple cycle it goes through every round. Once that feels natural, the S box, MixColumns, rounds, and key schedule stop looking like magic and start looking like code you can reason about.